Euhelopus was a sauropod dinosaur which lived in eastern China during the early Cretaceous Period approximately 130-112 million years ago. Fossils of this animal were found in the early 20th Century within the rocks of the Meng-Yin Formation within Shandong Province in northeastern China.

In the 1800s and early 1900s, numerous foreign powers – including multiple European nations, the United States, and the Japanese Empire – established themselves within China (arguably beginning with Britain’s takeover of Hong Kong following the Opium Wars). These powers negotiated treaties with the imperial Chinese government which enabled them to establish outposts within Chinese cities, and in some cases taking control of entire cities, which would be administered under their laws rather than Chinese law. These outposts were called “treaty ports”, and they were, in essence, colonies without actually being called colonies. These foreign powers not only controlled these cities, but dominated the regions around these cities, forming “spheres of influence” (Craig et al 2012, page 713).

In 1898, the German Empire coerced the Chinese imperial government into signing an agreement known as the Kiautschou Bay Concession, in which the Chinese leased control of Shandong Province’s Jiaozhou Bay (then known as Kiao-chou and numerous versions of that name) to the Germans for a period of 99 years. The nearby settlement of Qingdao (then known as Tsingtao) became the “treaty port” of the German Empire within eastern China. In total, the Germans exercised direct control over an area within Shandong Province measuring 213 square miles, and exerted political, economic, and military dominance over the remainder of the province (Pike 2015, pages 18, 22; Fuchs et al 2018, pages 130-131).

Because virtually the whole of Shandong Province was under German administration, a lot of Germans had settled there, including Christian missionaries. In 1913, a German Catholic missionary named Father Mertens stumbled upon some fossilized bones while traversing the countryside around the village of Ning Chia Kou, near the city of Meng-Yin in central Shandong Province. This area was well-known to the locals as a place where fossils could be found, which they called “dragon bones”. However, no further initiative was taken to learn more about these intriguing finds (T’an 1923, pages 96, 111, 123-124).

In 1914, Johan G. Andersson, the director of the National Geological Survey of Sweden, was invited to come to China to work alongside the Chinese Geological Survey in the quest to find new iron and coal deposits which China’s burgeoning industrial infrastructure could exploit. Andersson also had an interest in Cenozoic Era paleontology and Neolithic archaeology, and he was hoping to get the chance to do some fossil and artifact hunting while he was there (T’an 1923, page 96; Högseliusa and Song 2021, pages 158-176).

In 1917, a German mining engineer named Mr. W. Behagel showed a large sandstone block to the Chinese geologist Dr. Ding Wen-Jiang, also known by the pseudonym V. K. Ting. This block contained three large fossilized vertebrae which evidently belonged to a dinosaur of some sort. This block, in fact, belonged to the cache of bones which had been discovered by Father Mertens a few years earlier at Ning Chia Kou. However, this engineer didn’t know the exact spot where these fossils had come from. Ding contacted his colleague H. C. T’an and told him to go to Meng-Yin and find the exact location where these fossils had been unearthed. Unfortunately, even after conducting a thorough search of the area, and even asking the locals where these “dragon bones” had come from, T’an ended his search empty-handed (T’an 1923, pages 95-96, 124).

In November 1922, the Swedish geologist Johan G. Andersson and the Chinese geologist H. C. T’an journeyed to Shandong Province for the purpose to surveying the province’s rock strata. Their goal was to locate and excavate Eocene strata, but they got more than what they bargained for. When they surveyed the Meng-Yin and Lai-Wu valleys, they not only found Eocene fossils, but they also found fossils within Mesozoic-dated rock layers, including dinosaur bones. Andersson recommended that further excavations of the area ought to be conducted the following year (T’an 1923, pages 96, 119-120).

In the Spring of 1923, Andersson dispatched his assistant, the Austrian paleontologist Otto Zdansky, to survey and excavate for fossils in the Meng-Yin, Lai-Wu, and Fe Hsien valleys within central Shandong Province. Meanwhile, H. C. T’an surveyed the Lai-Yang, Chiao Hsien, and Chu Ch’eng districts in western Shandong. Both of these expeditions were successful. At Ning Chia Kou near Meng-Yin, Otto Zdansky and his team uncovered two partial skeletons of a sauropod dinosaur (collection ID codes: PMU 24705 and PMU 24706) which were unearthed approximately 3 km apart. The rocks which the bones were found within were tentatively dated to the lower Cretaceous Period, but this date wasn’t narrowed down further. A report of these finds was published in 1923 (T’an 1923, pages 96-97, 113, 120-122, 124, 135; Poropat 2013, page 105).

The fossils were taken to Sweden for further analysis (T’an 1923, pages 122, 124) and were housed within the Paleontological Museum of Uppsala University (PMU). In 1929, the Swedish paleontologist Carl Wiman named the sauropod dinosaur Helopus, meaning “marsh/swamp foot” due to the belief that its huge feet served the purpose of snowshoes to walk across swampy ground without sinking (Wiman 1929). However, the name Helopus was already used for a species of bird, so in 1956, the name was slightly altered to Euhelopus, “good/true marsh foot”) by the American paleontologist Alfred S. Romer (Poropat 2013, pages 104-107).

In 1934, another expedition was undertaken in the same locality where one of the skeletons had been found, and even more bones were unearthed which hadn’t been excavated earlier, consisting of a left scapulocoracoid, right coracoid and right humerus (Young 1935, pages 519-533). Regrettably, these bones have since disappeared (Wilson and Upchurch 2009, pages 201-202).

Because both the skeletons of this animal are only partial, it’s uncertain how large Euhelopus grew. Various sources give wide-ranging estimates of 11-15 meters (35-50 feet) (Dodson 1993, page 70; Paul 2010, page 178).

Other fossils which were found in the area include at least three species of freshwater fish, numerous species of mollusks and crustaceans, turtles, and an unknown stegosaur (which might be Wuerhosaurus, but we can’t be sure) (Grabau 1923, pages 143-182; T’an 1923, pages 95-135; Weishampel et al 2004, page 551).

The Swedish paleontologist Carl Wiman believed that Euhelopus belonged in its own family, called Helopodidae, due to it possessing a combination of anatomical features found in a variety of sauropod groups. In the 1950s, it was believed that Euhelopus was a close relative of the North American sauropod Brachiosaurus. This was altered in the 1970s to 1990s, which stated that it was actually more closely related to Camarasaurus (Dodson 1993, page 70; Lessem and Glut 1993, page 187), and it’s easy to see why because the skulls of the two species look very similar. Later, it was believed to be a member of its own family, called Euhelopodidae. In 2009, it was shown that it was an ancestor to the titanosaurs, which is the group of sauropods which would dominate the Cretaceous Period (Wilson and Upchurch, 2009, page 200; Poropat 2013, pages 106-107; Poropat and Kear 2013: e79932).

There has been some confusion as to when Euhelopus existed. In the early 1920s, it was stated that the rocks which the bones had been found in dated to the early Cretaceous Period (T’an 1923, pages 113, 120-121). A. W. Grabau dated the lower Meng-Yin beds where these fossils were found as being concurrent with the Wealden Group of southern England (Grabau 1923, page 144), which broadly dates 140-125 MYA. In the 1980s and 1990s, it was claimed that the rocks dated to the late Jurassic around 156-150 MYA (Mateer and McIntosh 1985, pages 125, 129; Dodson 1993, page 70; Lessem and Glut 1993, page 187). In 2009, these dates were again updated to the Barremian and Aptian Stages of the early and middle Cretaceous Period, approximately 130-112 MYA (Wilson and Upchurch 2009, page 204). In 2010, it was stated to be the late Jurassic Period, but this statement may be based upon earlier research (Paul 2010, page 178).

Euhelopus also might have lived in Manchuria during the early Cretaceous around 125 MYA. Teeth have been found within the rocks of the Lujiatun Beds of the Yixian Formation (famous for its numerous fossils of small feathered dinosaurs) which look similar to the teeth of Euhelopus. For that reason, these teeth were classified as “cf. Euhelopus sp.”, meaning “similar in shape to Euhelopus, species unknown”, although a more positive identification wasn’t made (Barrett and Wang 2007, pages 265-271).

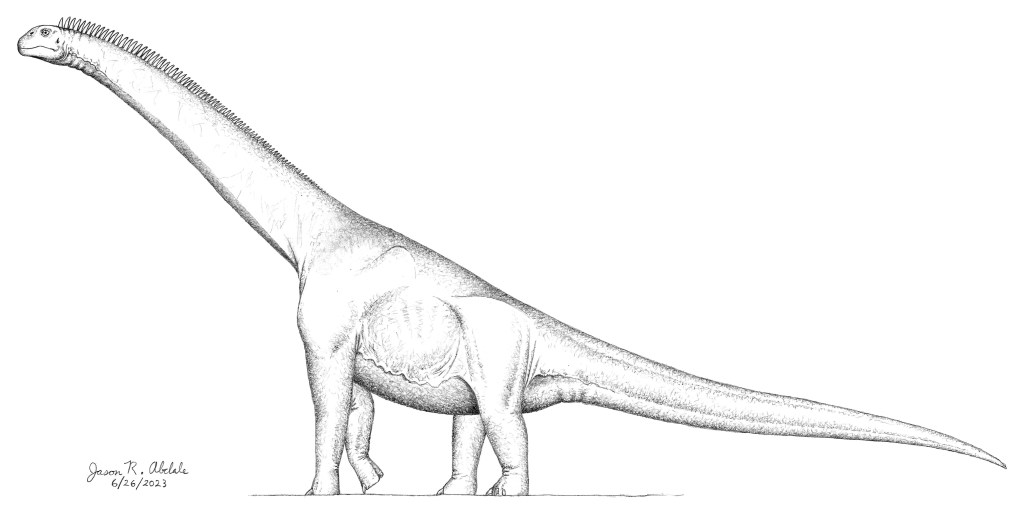

Below is a drawing that I made of Euhelopus, made with No.2 pencil and colored pencils on printer paper.

Euhelopus zdanskyi. © Jason R. Abdale (June 26, 2023).

If you enjoy these drawings and articles, please click the “like” button, and leave a comment to let me know what you think. Subscribe to this blog if you wish to be immediately informed whenever a new post is published. Kindly check out my pages on Redbubble and Fine Art America if you want to purchase merch of my artwork.

Bibliography

Barrett, Paul M.; Wang, Xiao-Lin (2007). “Basal titanosauriform (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) teeth from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of Liaoning Province, China”. Palaeoworld, volume 16, issue 4 (December 2007). Pages 265-271.

Craig, Albert M.; Graham, William A.; Kagan, Donald; Ozment, Steven; Turner, Frank M., eds. The Heritage of World Civilizations, Brief Fifth Edition, Volume 2: Since 1500. Boston: Prentice Hall, 2012.

Dodson, Peter, ed. The Age of Dinosaurs. Lincolnwood: Publications International, Ltd., 1993.

Fuchs, Eckhardt; Kasahara, Tokushi; Saaler, Sven, eds. A New Modern History of East Asia. Gottingen: V & R Academic, 2018.

Grabau, A. W. (1923). “Cretaceous Fossils from Shantung”. Bulletin of the Geological Survey of China, number 5, part 2 (December 1923). Pages 143-182.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Geological_Bulletin/WAyoeBSmPgMC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=1923+New+research+on+the+Mesozoic+and+early+Tertiary+geology+in+Shantung&pg=PA93-IA60&printsec=frontcover.

Högseliusa, Per; Song, Yunwei (2021). “Extractive visions: Sweden’s quest for China’s natural resources,1913–1917”. Scandinavian Economic History Review, volume 69, issue 2 (2021). Pages 158-176.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03585522.2020.1789731.

Lessem, Don; Glut, Donald F. The Dinosaur Society Dinosaur Encyclopedia. New York: Random House, 1993.

Mateer, Niall J.; McIntosh, John S. (1985). “A new reconstruction of the skull of Euhelopus zdanskyi (Saurischia, Sauropoda)”. Bulletin of the Geological Institution of the University of Uppsala (new series), volume 11 (October 1, 1985). Pages 124-132.

https://paleoarchive.com/literature/Mateer&McIntosh1985-NewReconstructionSkullEuhelopusZdanskyi.pdf.

Paul, Gregory S. The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, 1st Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Pike, Francis. Hirohito’s War: The Pacific War, 1941-1945. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

Poropat, Stephen F.; Kear, Benjamin P. (2013). “Photographic Atlas and Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of the Holotype Skull of Euhelopus zdanskyi with Description of Additional Cranial Elements”. PLOS One, volume 8, issue 11 (November 21, 2013): e79932.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0079932.

Poropat, Stephen F. (2013). “Carl Wiman’s sauropods: The Uppsala Museum of Evolution’s collection”. G.F.F., volume 135, issue 1 (March 2013). Pages 104-119.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257366962_Carl_Wiman’s_sauropods_The_Uppsala_Museum_of_Evolution’s_collection.

T’an, H. C. (1923). “New Research on the Mesozoic and Early Tertiary Geology in Shantung”. Bulletin of the Geological Survey of China, number 5, part 2 (December 1923). Pages 95-135.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Geological_Bulletin/WAyoeBSmPgMC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=1923+New+research+on+the+Mesozoic+and+early+Tertiary+geology+in+Shantung&pg=PA93-IA60&printsec=frontcover.

Weishampel, David B.; Barrett, Paul M.; Coria, Rudolfo A.; Le Loeuff, Jean; Xing, Xu; Xijin, Zhao; Sahni, Ashok; Gomani, Elizabeth M. P.; Noto, Christopher R. (2004). “Dinosaur distribution”. In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmolska, Halszka, eds., The Dinosauria, 2nd Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. Pages 517-606.

Wilson, Jeffrey A.; Upchurch, Paul (2009). “Redescription and reassessment of the phylogenetic affinities of Euhelopus zdanskyi (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Early Cretaceous of China”. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, volume 7, issue 2. Pages 199-239.

Wiman, C. (1929). “Die Kreide-Dinosaurier aus Shantung”. Palaeontologia Sinica, Series C, issue 6. Pages 1-67.

Young, C. C. (1935). “Dinosaurian remains from Mengyin, Shantung”. Bulletin of the Geological Society of China, volume 14, issue 4 (November 1935). Pages 519-533.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment