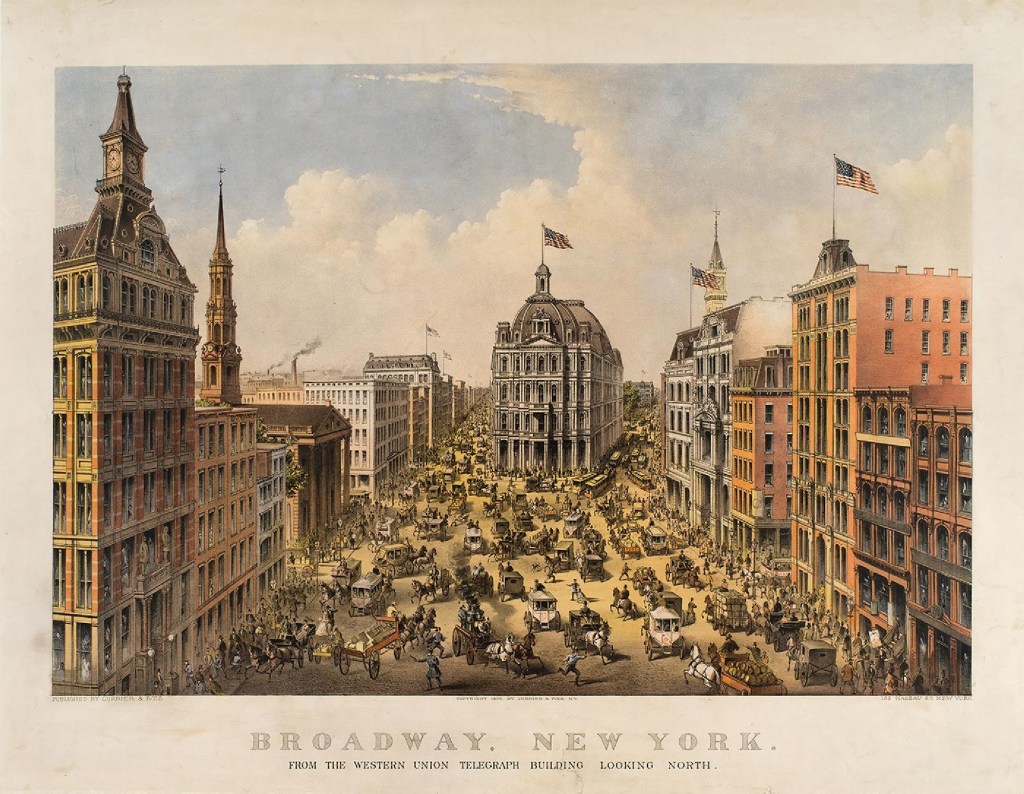

“Broadway, New York. From the Western Union Telegraph Building, looking North”. Hand-colored lithograph, published by Currier & Ives (1875). The New-York Historical Society.

People have a certain conception of what the past was like. They like to think that things were better, way back when, in the good ol’ days. These sentiments are largely the product of popular media portrayals of the way things used to be. But these ideas are, like the portrayals themselves on stage and screen, largely works of fiction. People often find themselves wistfully longing for a past that never truly existed. As a historian, I can say with all honesty that the way we think history happened versus the way it actually happened are often two completely different things.

For example, if you were to go back in time and visit New York City in the 19th Century, your initial reaction would almost certainly be an overpowering revulsion from the abominable stench. Garbage and excrement lay around everywhere. Dead animals lay rotting in gutters, and mangey dogs and alleycats fought each other over whatever edible scraps they could find. Filthy skin-and-bones barefoot children suffering from rickets, TB, and ringworm wearing torn and patched rags for clothing stuck their hands out asking for pennies, or maybe a gang of them swarmed onto you and robbed you of everything that you had.

A group of children play in a gutter near a dead horse on West 125th Street, 1903. It was not uncommon for dead animals to be left to rot along the curb for days or weeks. Photograph by Joseph Byron. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016794664/.

Like every major city in the 19th Century, animals lived side-by-side with humans. Pigs frequently ambled about in city streets to eat whatever garbage was dumped out by homes and shops. It was an efficient method of waste disposal – the pigs ate the garbage, and when they got fat enough, the people ate the pigs. In New York City, the practice had been going on since the 1600s when the area was controlled as a Dutch colony. By the 1820s, it’s estimated that as many as 20,000 pigs roamed Manhattan’s streets and alleys (“New York Pork: A Porcine History of the Big Apple”). It wouldn’t be until 1881 that the New York City government established the Department of Sanitation whose army of street cleaners would take over the pigs’ former position (“When the ‘White Wings’ cleaned up New York”). There were no automobiles, and few trains, so most of the legwork of hauling passengers and cargo was done by horse-drawn waggons and carriages. These vehicles cluttered up New York City’s streets the same way that taxi cabs and Uber cars do today…and the horses crapped everywhere. Everyplace that you looked, the cobblestone streets of NYC would be carpeted with stinking rancid masses of horse manure. Even today, the usage of horse-drawn carriages in Manhattan is a contentious one. There were also dogs – literally thousands or even tens of thousands of them. We typically think of cities that have large numbers of feral or stray dogs as being largely a Latin American phenomenon, in places like Rio De Janeiro or Mexico City. During the 19th Century, every major city within the United States had a sizeable population of stray dogs roaming the streets.

For the people of New York City and elsewhere during the 19th Century, people who lived and worked alongside animals every day, there was very little sympathy directed towards our four-legged neighbors. Animals were not pets – they were tools, they were labor, they were nothing more than living machines whose only purpose was to be Mankind’s obedient and subservient subjects, as was sanctioned in the Book of Genesis. Any animals which did not perform their jobs satisfactorily, or who were regarded as an annoying nuisance, were beaten or killed. These people thought absolutely nothing of whipping horses, beating cats, and shooting dogs dead on the street. It was as normal to them as getting dressed and eating your breakfast. You might find all of this very disturbing, as well you should, but keep in mind that animal cruelty was commonplace in both Europe and North America until relatively recently.

Of all of the animals which could be found on New York City’s streets in the 19th Century, the dogs were regarded as the most problematic. Some of these were escaped pets, but most of them were feral dogs which were not quite tame, often travelling around in packs like wolves. These street dogs were a public nuisance, they pooped everywhere, they caused carriage accidents, they sometimes bit people, and there was a fear amongst the public of contracting rabies.

Beginning in 1785, the government of New York City passed various laws and ordinances to keep dogs off of the streets. Such laws were reinstated or added to in 1802, 1803, and 1808 – none of them seemed to do any good (McNeur 2014, page 13). Then in 1811, the NYC government decided to enact more draconian measures to solve the problem. The year 1811 initiated what became a city-wide campaign of extermination against NYC’s stray dogs which would continue for over eighty years.

That year, the government of New York City passed the “Law Concerning Dogs”, which established a $3 tax for owning a dog and also created an office called the Dog Register and Collector who would be responsible for collecting the tax. Moreover, anybody was given the freedom to kill any stray dogs that were found outside of Manhattan’s downtown “Lamp District”. The issuance of this law resulted in a lot of public backlash, as angry crowds mobbed dog-catcher waggons and released the captured dogs back out onto the streets (“Killing Stray Dogs in early 19th century New York”).

In the 1830s, the New York City government declared that a bounty of $1 per carcass (which would be roughly $35 in 2023) would be paid for any dead dog brought in. Naturally, incentivizing the killing of animals by offering up monetary bounties led to a massive spike of dog deaths as impoverished New Yorkers saw this as a chance to make a quick buck. In fact, the city’s Dog Register and Collector was hard-pressed to deal with the massive number of dead dogs which were brought into the office every day. In 1836, 8,000 stray dogs were killed within New York City that year. (“Killing Stray Dogs in early 19th century New York”). In 1848, the New York Daily Herald published a piece describing several incidents of gangs of local children chasing after and killing loose dogs and then bringing them to the Dog Register and Collector to collect the bounty (Crawley 2021, page 35). Some individuals, knowing that dead dogs had bounties on their heads, stole people’s pets (sometimes snatching them right out of their hands!), killed them, and then raced off to the Dog Register and Collector to claim their reward (“New York City Used To Kill Its Stray Dogs By Drowning Them”). In 1874, the New York Tribune published an article stating that the tempting lure of a few coins resulted in unscrupulous boys stealing dogs out of people’s yards, and even breaking into people’s houses to steal the dogs inside (Unti 2002, page 472).

By no means was New York City alone in this regard. Similar capture-and-kill initiatives were taken up in places like Philadelphia and Baltimore. In some places, the wholesale killing of street dogs was met with public approval (Crawley 2021, page 32).

To the public, the big threat to public health and safety was not the dogs themselves, but rather what they could potentially carry – rabies, or “hydrophobia” as it was termed in those days. Despite the fact that confirmed cases of rabies were very low (just 22 cases reported within all of New York state between 1866-1871), people feared contracting the potentially fatal disease due to the close proximity of stray dogs running around the streets who either may or may not be infected. People dreaded being bitten by any dog of any size because they automatically assumed that all stray dogs were rabid. Within New York City, one dog was regarded as being particularly prone to carrying rabies – the “spitz”. Incendiary newspaper reports stated without any substantiation that spitz breeds were more likely to carry rabies than other dog breeds, and called for the outright extermination of all spitz dogs within the city for the sake of public health. Even so, there were some sensible voices crying out in the wilderness. One article published by The New York Times in 1868 stated that the panic caused by the fear of contracting rabies had done more harm than the actual disease itself (Crawley 2021, pages 30-33).

In 1850, the New York City government created “the Dog Bureau”, composed of three squads of ten men each commanded by a captain. They patrolled the streets armed with billy clubs and set upon any dog that they saw which didn’t possess a collar or a muzzle (Crawley 2021, page 33).

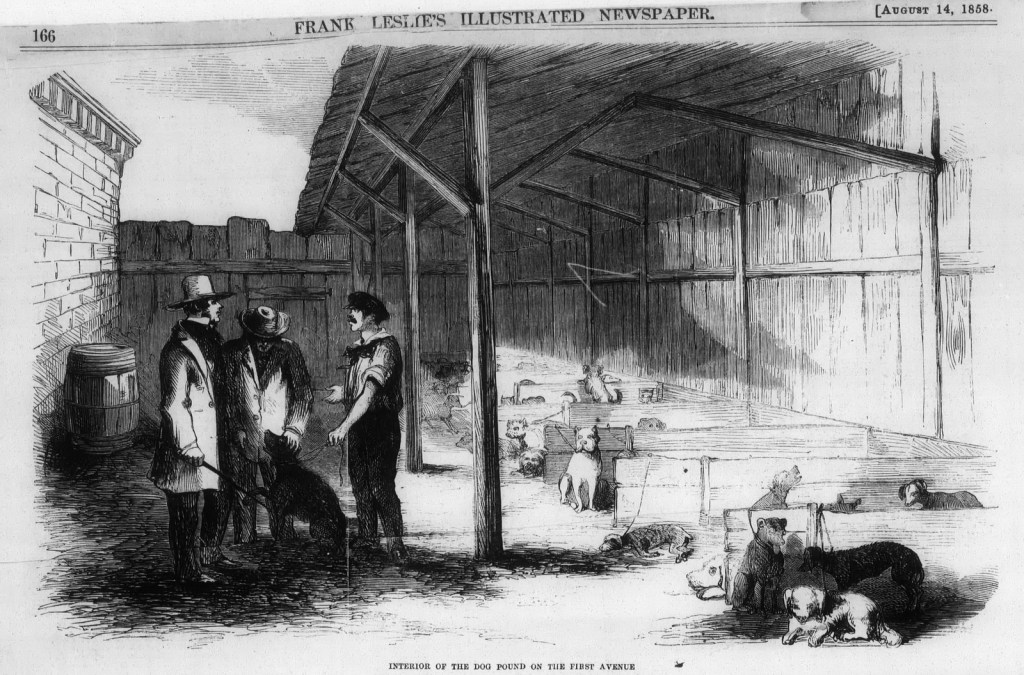

The following year in 1851, NYC established its first municipal dog pound, located at the intersection of East 31st Street and 1st Avenue. The building was nothing more than a wooden shed which belonged to a nearby varnish factory – a series of medical buildings stand upon the site today (“‘Where the Dogs Go To’ (NYC in 1858)”). However, while there had been support amongst the population concerning putting the street mongrels out of their misery with a hard sharp thud to the skull with a billy club, there was a lot of NIMBY-ism amongst the city’s inhabitants concerning where to put a dog pound. The issue of dog pounds continued to be a contentious one throughout the 1850s and 1860s, as various newspaper reporters, editors, or public comments either supported or opposed the practice (Crawley 2021, pages 33-34).

“Interior of the Dog Pound on the First Avenue”. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (August 14, 1858).

In 1855, William MacKellar, who served as the clerk to the NYC chief of police George W. Matsell, and who was by all accounts a very shady and disreputable character, came up with a brutally efficient solution to the Big Apple’s dog problem – drowning. If your dog was found on the street and captured by the city’s dog-catcher, you had just 24 hours to reclaim it. Any unclaimed dogs were drowned (“New York City Used To Kill Its Stray Dogs By Drowning Them”). A newspaper reporter for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper visited the dog pound in 1858, and actually witnessed one of these drownings. This is his report: “At sundown every day the animals are killed. This is done by drowning. A water-tight tank is provided, about six feet by eight, and seven feet high. A grating fits over it about six inches from the top. The dogs are put into this tank and the grating closed and firmly bolted down, and the tank is then filled with water and the dogs are thus drowned” (“‘Where the Dogs Go To’ (NYC in 1858)”).

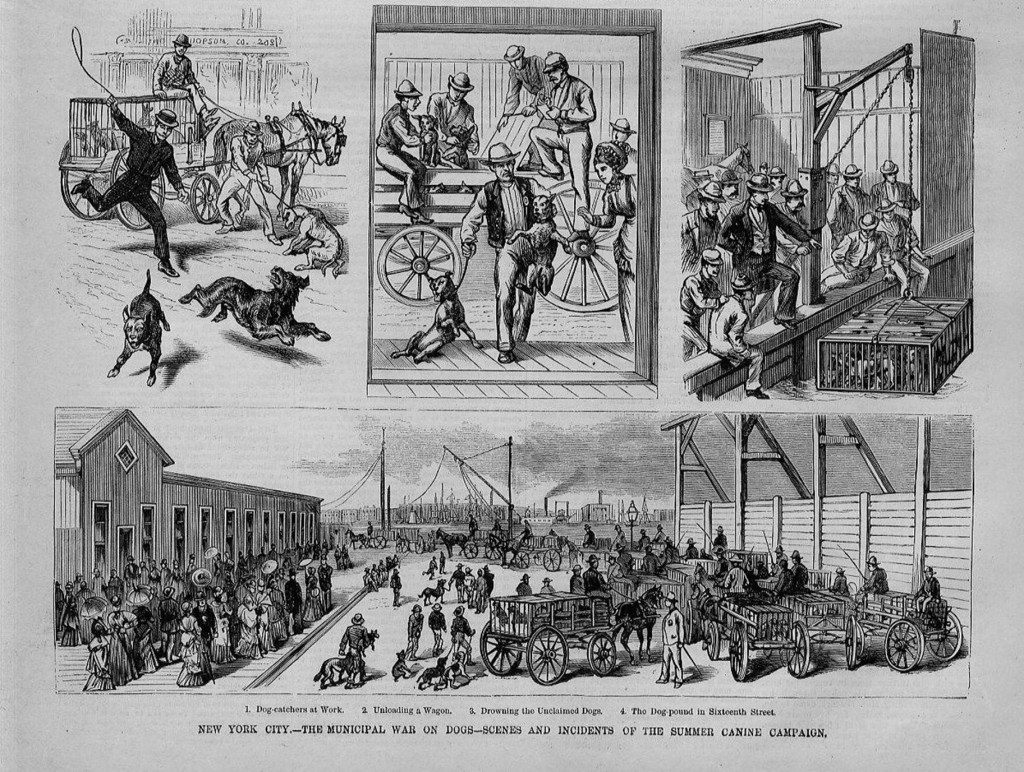

Eventually, drowning the dogs inside a tank was deemed to be insufficient. A new method was needed to kill as many dogs as possible as quickly as possible. So instead of drowning the dogs inside a tank, the dogs were locked inside iron cages and dumped into the East River. Regrettably, it’s estimated that less than 5% of the dogs which were captured were reclaimed by their owners – the rest of them met their fate in a watery grave (“New York City Used To Kill Its Stray Dogs By Drowning Them”). These mass drownings took place where East 26th Street meets the East River within the “Kips Bay” neighborhood of Manhattan, a stones’ throw away from where Bellevue Hospital now stands, and the spot was sadistically referred to as “the canine bath tub”. On July 8, 1877, 738 full-grown dogs and about twenty puppies were drowned at this spot in batches from 5:00 AM to 1:00 PM (“Where They Used to Drown the Dogs”). This was by no means an isolated occurrence. These mass drownings occurred almost every day for a period lasting nearly forty years, until the practice ended in 1894. Today, this location is covered with artificial landfill called “Waterside Plaza” and is dominated by high-rise luxury apartment buildings, spas, and tennis courts.

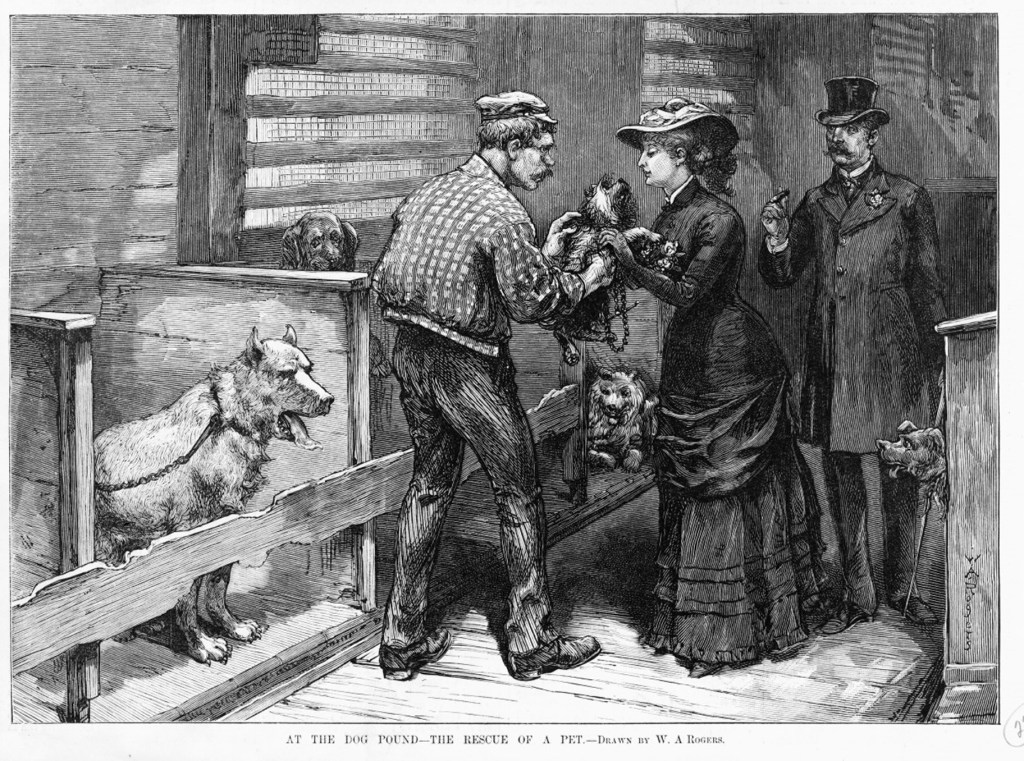

“At the Dog Pound – The Rescue of a Pet”, illustrated by W. A. Rogers for Harper’s Weekly (June 16, 1883).

An article published by The New York Times made the following comments: “One thing, however, is certain: dogs are useless animals in cities, and are a nuisance, independent of their habit of occasionally running mad; and the best dog law would be one that imposed so high a tax on the owners of curs that few people would care to keep them, and those who did would see to it that the animals did not run at large, muzzled or unmuzzled…The drowning of the dogs is not a very pleasant sight. But still it is better that such should be their end than that our worthy citizens should live in fear of a bite. Better indeed that New-York, like Venice be dogless” (“New York City Used To Kill Its Stray Dogs By Drowning Them”).

“New York City – The Municipal War on Dogs – Scenes and Incidents of the Summer Canine Campaign”. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (July 1877).

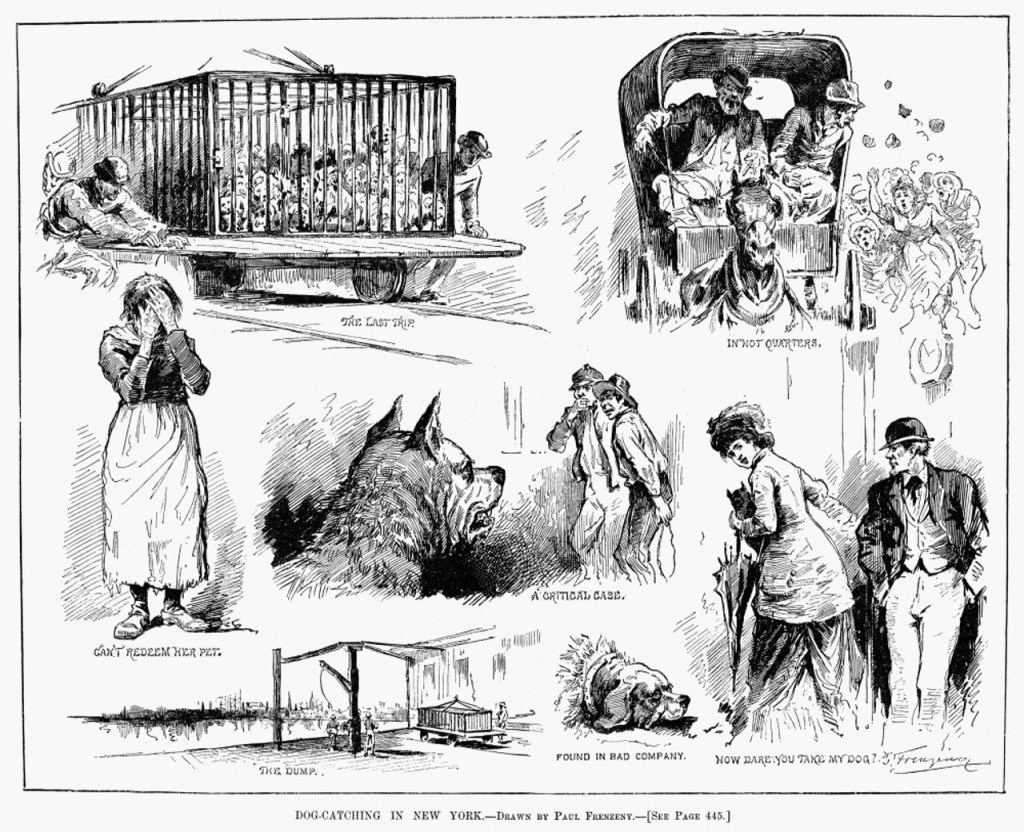

“Dog-Catching in New York”, illustrated by Paul Frenzeny for Harper’s Weekly (1882).

Interestingly, this widespread caninicide resulted in discussions amongst New Yorkers about the morality of such laws and also of the ethical standards of those participating in it. It is generally known amongst psychiatrists, psychologists, and criminologists that a penchant for torturing or killing animals is indicative of a psychopathic mentality. Middle class and upper class New Yorkers claimed that those who participated in the widespread killing of dogs became more likely to live a life of crime. Indeed, those who were involved in capturing and killing dogs were regarded as being a villainous lot who had become desensitized to inflicting violence and to the sight of blood, and were therefore likely to commit violence upon other people as well as animals. A person who beats a dog to death today might beat a person to death tomorrow (Crawley 2021, pages 35-37; “Killing Stray Dogs in early 19th century New York”).

In 1866, the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (A.S.P.C.A.) was formed in New York City, based upon the similarly-named Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals which had been founded in Britain in 1824 (“Not your mother’s animal shelter”). The A.S.P.C.A.’s first president Henry Bergh was largely regarded as an irritating irksome pest by his contemporaries who couldn’t care less about cockfights, whipping horses, or drowning cats and dogs; they dubbed him “the Great Meddler”. He was frequently ridiculed and insulted, harassed, assaulted, and even received death threats. Still, his social and political connections to those in high places meant that his ideas were listened to while similar voices protesting animal cruelty weren’t. Little by little over the course of decades, the A.S.P.C.A.’s firm stance against animal cruelty began to take effect upon New York City’s population (“The ASPCA’s Founder Was Known as ‘The Great Meddler'”; “Henry Bergh: Angel in Top Hat or the Great Meddler?”).

To be fair, there had always been a faction within NYC which was opposed to the killing of the city’s street dogs, but their voices of protest had largely been ignored by those in positions of power. Yet by the 1880s, the prevailing attitude within NYC concerning stray dogs appears to have changed from contempt to compassion. Even The New York Times, which had earlier called stray dogs a nuisance which deserved to be exterminated, now treated the city’s canines with sympathy. On June 2, 1881, The New York Times published an article on how NYC was dealing with the problem of street dogs, which reads as follows (“New York City Used To Kill Its Stray Dogs By Drowning Them”):

Dogs have no right to live after the 1st of June, according to the Mayor, unless they are wealthy enough to wear a collar with a brass certificate of license attached to it. The “close season” for dogs in New-York began yesterday and the pound was opened. In this institution last year over 8,000 dogs were put to death, and there was thus destroyed more intelligence, more faithfulness, and more common sense than ever bothered some of their persecutors.

The pound was empty yesterday, but the 15 dog-catchers are to go to work immediately, and it will soon have some boarders. It is under the charge of Capt. John McMahon and several assistants, who have made very complete arrangements for the capture and slaughter of unclaimed dogs.

There is an office in front with a big sign on it. “Department of Dogs.” This is separated inside into two parts by a railing. The officers of the concern are on one side of the railing. and a police-man and the Indignant public are on the other side. In the reception room, to which the better dogs are taken, are 130 kennels, each supplied with a chain. Troughs run around the ends of these kennels, containing constantly four inches of water, to supply thirsty dogs with a drink.

At one end of the room are two large private kennels for the accommodation of such fancy dogs as may be picked up. There is a pen at one side, just the size of the iron cage, in which the dogs are drowned. This is filled with the poor creatures, and they are then driven into the cage. The cage rests upon a little car, which is run to the water’s edge. Over the edge of the river hangs a derrick, from the cross-beam of which dangles a big iron hook. The hook is fastened in an iron ring in the top of the cage, which is then hoisted with a rope and pulley till it is clear of the car, when it is swung over the river and lowered. In six minutes the dogs delight to bark and bite no longer, and the cage is hoisted up again.

Their dead bodies are taken to Barren Island where they are “manufactured” into various articles. Just what those articles are, perhaps it is better for the public not to conjecture. The pound is at the foot of Sixteenth-street, East River, and there valuable or pet dogs may be re-claimed upon payment of the legal fee. When a dog sees a man come alone with a big circular badge on his heart and a number on the badge, let that dog lie low—it is the catcher!

In 1888, Mayor Abram S. Hewitt of New York City called for a more humane way to deal with the city’s stray dog dilemma rather than the mass drownings which had been employed since 1855. Various methods were tried including death by electrocution, asphyxiation with carbon dioxide gas, or suffocation with chloroform – none of them proved sustainably effective (“New York City Used To Kill Its Stray Dogs By Drowning Them”).

In 1894, John P. Haines, who had succeeded to the presidency of the A.S.P.C.A., successfully pressured the New York City legislature into passing a new law concerning what to do with the city’s stray dogs and cats. From now on, any stray cats and dogs which were captured would be taken to a “Shelter for Animals” located at 448 East 102nd Street on the bank of the East River. The structure measured 60 feet long and 14 feet wide, and was heated, lighted, and ventilated to minimize discomfort to the animals inside. The animals would be held there for 48 hours – twice as long as the customary 24 hours in the city pound. During that time, the shelter staff would endeavor as hard as possible to get the animals adopted into good homes. However, once the 48 hours were up, they would be killed, often by poison gas (“New York City Used To Kill Its Stray Dogs By Drowning Them”).

Also in 1894, the New York state government passed a law “for the better protection of lost and strayed animals, and for securing the rights of the owners thereof” (“New York Lost and Strayed Animals 115/1894 Law”), which applied exclusively to New York City. This law required that anybody who owned a dog needed to obtain a license for each dog owned and which needed to be renewed annually. Part of the money collected would be used to fund the city’s office of animal population control. A licensed dog was required to wear a collar around its neck at all times with an identification tag showing the license number. Anybody who owned a dog without a license or neglected to renew their license after it expired would be punished with a fine of up to $75 (that’s over $2,600 in 2023’s money). The law said “Three quarters of any amount paid as a penalty for a violation pursuant to this section shall be forwarded to the city comptroller for deposit in the animal population control fund created pursuant to section 17-812 of the administrative code of the city of New York, and the remainder shall be used solely for carrying out the provisions of this act, establishing, maintaining, or funding shelters for lost, strayed, or homeless animals, providing or funding public education regarding responsible animal care and dog licensing requirements, and conducting other animal care and control activities” (“New York Lost and Strayed Animals 115/1894 Law”). Any unlicensed dog which was seized, and not redeemed within 48 hours, would be killed. Likewise, any cat which was found and seized which didn’t possess a collar and a tag giving the name and address of the cat’s owner would be killed within 48 hours unless the owner redeemed it – the price of which for both dogs and cats was $3. The law further stated that, from now on, the A.S.P.C.A. would handle the operation of the impoundment facilities rather than the NYC government. Therefore, this law ended NYC’s direct running of the dog pounds and abolished the office of the city dog-catcher (“New York Lost and Strayed Animals 115/1894 Law”). With the A.S.P.C.A. now in charge of New York City’s canine problem, the mass drownings on the East River came to an end.

However, the transference of animal control from the NYC government to the A.S.P.C.A. didn’t end the mass killings. As mentioned before, the animal shelters held any captured animals for only 48 hours, and then they would be put to death by poison gas, and the numbers killed could be quite high. In 1895, 21,741 dogs and 24,140 cats were brought to the “animal shelter” on 102nd Street. 95% of these animals were sent to the gas chamber (Guenther 2020).

As the 19th Century transitioned to the 20th, attitudes concerning animal welfare continued to turn positive. The A.S.P.C.A. was soon joined by other animal welfare organizations in other American cities, such as the Women’s Pennsylvania Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), the Morris Refuge Association (also based in Philadelphia), the Animal Rescue League (Boston, Massachusetts), the Humane Animal League (Los Angeles, California) (McCrea 1910, pages 87-88, 157), and the Humane Society. By 1907, every state in the United States had at least one law forbidding cruelty to animals (“Not your mother’s animal shelter”). At a meeting of UNESCO in Paris, France on October 15, 1978, a “Universal Declaration of Animal Rights” was issued. Within this document’s fourteen articles, it was asserted that all animals have rights, including the right to live, the right to be free from abuse and torture, and the right to be treated with kindness and respect (“Universal declaration of animal rights (15 October 1978)”). 150 years earlier, such statements would have been laughed at. How things have changed.

Let’s hope that they continue to change, because there’s still a lot of progress to be made. Various animal welfare organizations still euthanize thousands of animals every year. There has been a vocal outcry against this and an increasing demand for “no kill” animal shelters. Critics say that such goals are impossible because there are simply too many animals for under-manned and under-funded humane organizations to deal with. The animal shelters are already overcrowded, and trying to save every animal is a pipe dream. A possible solution, they say, is to have the animals sterilized so that they cannot reproduce, and thereby reduce the population long-term. Even if no animals are killed, they could spend months or even years locked inside kennels waiting for somebody to adopt them – some animals spend literally their entire lives in confinement, waiting for a rescue that never comes.

This article is dedicated to the memory of “man’s best friend”, everywhere.

Bibliography

Accessible Archives. “‘Where the Dogs Go To’ (NYC in 1858)”, by J. D. Thomas (August 14, 2015).

https://www.accessible-archives.com/2015/08/frank-leslies-where-the-dogs-go-to-nyc-1858/. Accessed on July 21, 2023.

Crawley, Melissa. Beware of Dog: How Media Portrays the Aggressive Canine. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2021.

Constitutii Files. “Universal declaration of animal rights (15 October 1978)”.

https://constitutii.files.wordpress.com/2016/06/file-id-607.pdf. Accessed on July 21, 2023.

Ephemeral New York. “When the ‘White Wings’ cleaned up New York”.

https://ephemeralnewyork.wordpress.com/2008/08/11/when-the-white-wings-cleaned-up-new-york/. Accessed on July 22, 2023.

Guenther, Katja M. The Lives and Deaths of Shelter Animals. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2020.

McCrea, Roswell Cheney. The Humane Movement: A Descriptive Survey. New York: Columbia University Press, 1910.

McNeur, Catherine. Taming Manhattan: Environmental Battles in the Antebellum City. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014.

New York Almanack. “New York Pork: A Porcine History of the Big Apple”, by Jaan Harskamp (February 19, 2023).

https://www.newyorkalmanack.com/2023/02/new-york-pork-pigs-on-broadway/#:~:text=Migrants%20and%20immigrants%20swarmed%20into,run%20loose%20in%20the%20streets. Accessed on July 21, 2023.

ONCLE. “New York Lost and Strayed Animals 115/1894 Law”.

https://law.onecle.com/new-york/lost-and-strayed-animals-115.1894/index.html. Accessed on July 21, 2023.

Smithsonian Magazine. “The ASPCA’s Founder Was Known as ‘The Great Meddler'”, by Kat Eschner (April 10, 2017).

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/aspcas-founder-was-known-great-meddler-180962792/. Accessed on July 21, 2023.

Sniffing the Past – Dogs and History. “Killing Stray Dogs in early 19th century New York”, by Chris Pearson (March 29, 2016).

https://sniffingthepast.wordpress.com/2016/03/29/killing-stray-dogs-in-early-19th-century-new-york/. Accessed on July 21, 2023.

Stuff Nobody Cares About. “New York City Used To Kill Its Stray Dogs By Drowning Them”.

https://stuffnobodycaresabout.com/2018/10/18/dogs-by-drowning/. Accessed on July 21, 2023.

The Humane Society of the United States. “Not your mother’s animal shelter”, by Bethany W. Adams (2018).

https://humanepro.org/magazine/articles/not-your-mothers-animal-shelter. Accessed on July 21, 2023.

The New-York Historical Society. “Henry Bergh: Angel in Top Hat or the Great Meddler?”, by Tammy Kiter (March 21, 2012).

https://www.nyhistory.org/blogs/henry-bergh-angel-in-top-hat-or-the-great-meddler. Accessed on July 21, 2023.

The New York Times. “Where They Used to Drown the Dogs”, by Jennifer Lee (September 30, 2008).

https://archive.nytimes.com/cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/09/30/where-they-used-to-drown-the-dogs/. Accessed on July 21, 2023.

Unti, Bernard Oreste (2002). “The quality of mercy: Organized animal protection in the United States, 1866-1930”. PhD thesis, American University.

Categories: History, Uncategorized

I was searching for a good history on this, and came across this article. Thank you for putting this all together.