Depiction of rioters and police during the New York City draft riots of 1863. Harper’s Weekly (August 1, 1863). Public domain image, Wikimedia Commons.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:New_York_Draft_Riots_-_Harpers_-_beating.jpg.

Anyone who has basic knowledge of the American Civil War or who has seen the Martin Scorsese film Gangs of New York has heard about the New York City Draft Riots of 1863. However, what you might not realize was that the violence and vandalism which occurred was not confined exclusively to the Big Apple. This article concerns an incident which is rather close-to-home for myself. I’ve lived my whole life in Flushing, in northern Queens, New York. Only a few miles to the south is the large bustling and arguably dangerous town of Jamaica. It was here in 1863 that a similar riot against the draft broke out, although not on the same scale as the one which erupted in Manhattan. This article is all about this little-known episode in New York’s history.

In the early heady days of the conflict in 1861, thousands of men enthusiastically rushed to their local enlistment offices eager to fight for the Union. Everyone assumed that it would be a short war, lasting for only one month or perhaps three at most. Then, the casualty reports started coming in. The Union Army suffered defeat after defeat in 1861 and 1862, resulting in tens of thousands of “boys in blue” going to an early grave. By the beginning of 1863, enthusiasm for the war had dampened, and volunteers were increasingly hard to come by (1).

Opposition to getting involved only increased following the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863. Many Northern whites scoffed at the idea of waging war to give freedom to Africans, whom they considered to be inferior in every way to whites. One of the hard truths of this time is that many – if not indeed most – Northerners were just as racially prejudiced against blacks as Southerners were. Being forced into battle with the distinct possibility of being killed for the purpose of granting slaves their freedom was not to their liking. In fact, thousands of Union soldiers deserted rather than go on fighting for such a cause (2).

On March 3, 1863, as a way to press men into military service whether they wanted to or not, Pres. Abraham Lincoln signed the Enrollment Act into law. Among its provisions, the law stated that all single men ages 20-45 as well as married men up to age 35 would be subjected to a draft lottery – whoever’s name was chosen would be ordered into military service. Both citizens and non-citizens would be subject to this law, and they would be required to serve for a period of two years. However, the law also contained various exemptions for military duty, including paying a $300 exemption fee (approximately $7,350 in 2023), or finding somebody who would serve in their place (3).

The terms of the Enrollment Act were obviously biased against poor and working-class men. Such slanting in favor of the rich and privileged was not exclusive to the Union side. In April 1862, the Confederate Congress passed its own draft ordinance (4), and amongst the Confederates, too, there were deferments in place which allowed the wealthy to avoid military service. Corporal Sam Watkins, a Confederate soldier from Tennessee, relates in his memoirs the frustrations that he and his comrades felt when they heard of the legal loop-holes which the rich were able to exploit: “A law was made by the Confederate States Congress about this time allowing every person who owned twenty negroes to go home. It gave us the blues; we wanted twenty negroes. Negro property suddenly became very valuable, and there was raised the howl of ‘rich man’s war, poor man’s fight'” (5). Keep in mind that Sam Watkins himself came from a very wealthy family – his father owned 100 slaves as well as a sizeable amount of land within Maury County, Tennessee valued at $104,250 according to the 1860 national census (about $3.86 million in 2023). Therefore, Sam Watkins was hardly in a position to claim that he was hard-up (6). Nevertheless, the slogan of “Rich man’s war, poor man’s fight” seems to have been quite common amongst soldiers of both the North and South during the Civil War, just as common as “F.T.A.” or “Foxtrot Tango Alpha” (“fuck the Army”) was during the Vietnam War.

Deferments like this had taken place in America both before the 1860s and since then, too. During the American Revolutionary War, people could avoid military service by paying a fee for someone else to take their place (7). Famously, during the Vietnam War, there was rampant criticism that the draft unfairly targeted poor working class people, ethnic minorities, those who lived in rural areas, those who weren’t currently enrolled in college, or simply anyone who didn’t have the right “friends in high places” who could take their name off of the selective service list. Such aggravation was immortalized in Creedence Clearwater Revival’s song “Fortunate Son”. These sentiments would have been familiar to the likes of those in both the Union and Confederate armies about the conflict being a “rich man’s war, poor man’s fight”.

Within the North, the announcement in the Spring of 1863 that people were now going to be forcibly inducted into the army through a military draft was met with widespread hollers of disapproval and only served to further escalate the hostile feelings that many Northerners had towards the federal government. As per military conscription quotas, Queens County, New York was ordered to conscript 1,603 of its men for service in the Union military, which was to be completed by July 15, 1863 (8). On June 6, 1863, a large quantity of military clothing was shipped to the city of Jamaica, which would be used to cloth the draftees once they were called into service (9). On July 14, 1863, the day before the scheduled draft was to take place, there was talk in Jamaica of trouble brewing. The sentiment of the townsfolk, and especially amongst the town’s immigrant Irish population, was palpably hostile towards the coming draft. By afternoon, rumors were spreading through the town that violence was likely to erupt that night. Henry Onderdock Jr. provides the most comprehensive account of what happened…

“An Irish anti-draft riot broke out in Jamaica, on the evening of July 14, 1863. Its purpose was to stop the draft which was to commence, next day. Rumors of intended violence were rife during the afternoon, and some friends of order felt disposed to arm in defense of Government: but timid counsels prevailed, and the village was left to the mercy of the rioters. About dusk they began to gather together. Someone cried out: ‘Now for the clothing!’ The mob then rushed to the building in Washington street, where the Government property was stored, with intent to destroy it. They, however, contented themselves (on the entreaty of some leading democrats) with taking out some boxes of soldiers’ clothing, which they broke open and piled in heaps, and then set on fire. The large pile, called ‘Mount Vesuvius’, was about ten feet high. The woolens did not readily burn, and some was carried off by Irish women for family use. The loss was $3,446.28 and consisted of 210 knit shirts, 80 pair stockings, 30 pair trousers, 59 knapsacks, 400 haversacks, 389 blankets, 153 canteens, and 523 blouses. The mob next proceeded to McHugh’s hotel, where they drank freely and without cost. The Provost Marshal’s Office was entered and the furniture broken. The draft wheel and papers had been removed that afternoon to a place of safety: and Col. [Edwin] Rose, with his subordinates had fled. This draft was put off ’till Sept. 2” (10).

During the course of the draft riots, African-American neighborhoods were some of the main targets of the rioters. Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Freemantle – the British officer seen in the 1993 movie Gettysburg – was visiting Manhattan when he saw a crowd of white men chasing after a black man, and they were all shouting that they were going to kill him. When Freemantle inquired to a bystander what the black man had done to make everyone chase after him, the fellow responded that blacks were hated because they were regarded as the cause of all of the recent troubles (11). In Manhattan and Brooklyn, black-owned businesses and homes were burned and numerous blacks were assaulted and murdered in the streets, often by their neighbors (12). On Staten Island, heavily-armed mobs burned down several houses where blacks lived. With Manhattan and Brooklyn engulfed in violence, many blacks who lived in those areas fled to Queens, where they believed the danger to be significantly less (13).

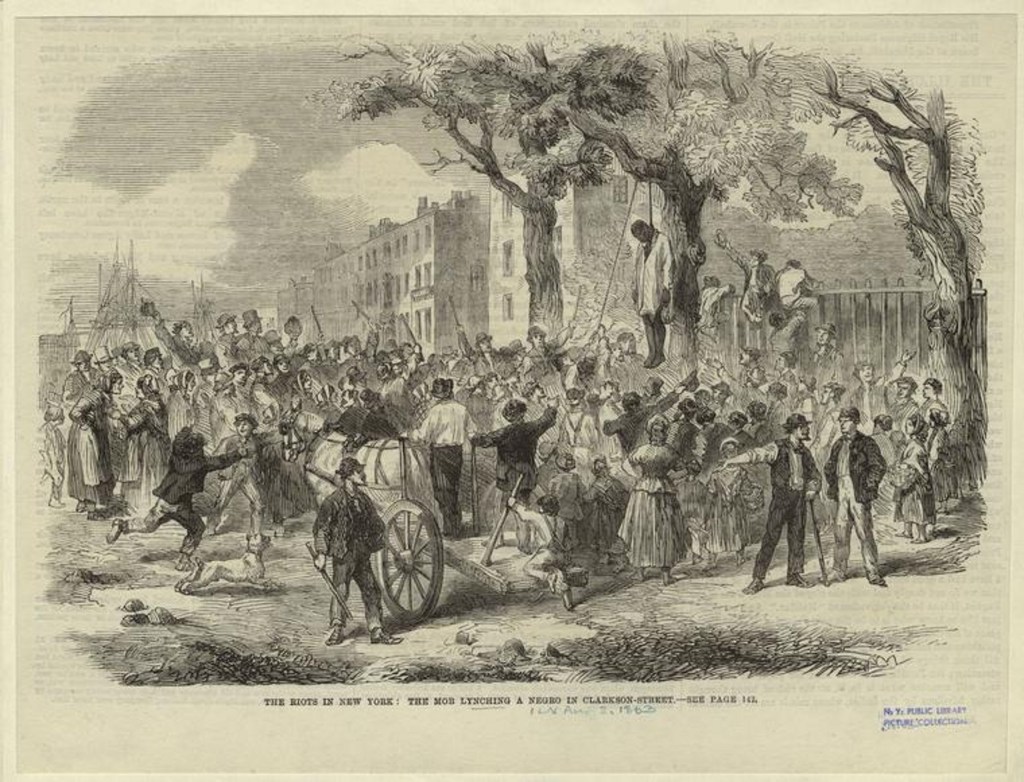

A white mob lynches a black man in Greenwich Village, Manhattan during the 1863 draft riots. Public domain image, New York Public Library.

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-2815-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

However, Queens wasn’t entirely peaceful. In Flushing, a group of Irish in the town threatened mob violence against Flushing’s black community. However, Flushing’s African-American population declared that they weren’t doing any harm to anyone, and that if any of them were attacked, they would inflict a double-blow upon the Irish. They stated that they would burn down two Irish homes if any one of theirs was burned down, and that they would kill two Irish men for each black man that was killed by them. Flushing’s Irish never followed up on their threat to attack the town’s blacks. On July 16, Brooklyn’s African-American community of Weeksville was apoplectic with terror when they heard a rumor that an angry mob from Jamaica was coming to attack them. Their menfolk quickly armed themselves and stood guard to bar this mob from descending upon the black neighborhood (14).

In September, the conscription quota for Queens County was reduced from 1,603 men to 852 men – slightly more than half the original number. Throughout the second half of the Civil War, the majority of soldiers who hailed from Queens enlisted only when the county government and local municipal governments offered them money in exchange for enlisting, sometimes as high as $600 per man (that’s about $14,700 in 2023) (15).

So that’s the story of the Jamaica draft riot – admittedly nowhere on the same scale as the riots which took place in Manhattan and Brooklyn, or even on Staten Island, but nevertheless still important for the study of Queens County history, if for no other reason than its historical obscurity.

If you enjoyed this article, please click the “like” button and leave a comment, if you wish. Also, consider becoming a subscriber so that you can be immediately notified when a new article is posted. I’ve got a couple of other Civil War articles in the works for this website so stay tuned.

Source Citations

- Roemer, Brevet-Major Jacob. Reminiscences of the War of Rebellion, 1861-1865. Flushing: The Estate of Jacob Roemer, 1897. Page 11.

- American Battlefield Trust. “Evidence for The Unpopular Mr. Lincoln: The People at the Polls 1860-1864”; Atun-Shei Films. “Was it REALLY the WAR of NORTHERN AGGRESSION?!?!?!”

- Yale Macmillan Center. “An Act for enrolling and calling out the national Forces”.

- Williams, David. Rich Man’s War: Class, Caste, and Confederate Defeat in the Lower Chattahoochee Valley. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011. Page 4.

- Watkins, Sam. Co. Aytch: A Confederate Memoir of the Civil War. New York: Touchstone, 2003. Page 32.

- Random Thoughts on History. “Sam Watkins and His Stake in Slavery”.

- Journals of the Continental Congress, volume 7 – January 1 to May 21, 1777. Page 262.

- Pelletreau, William Smith. A History of Long Island, Volume II. New York: Lewis Publishing Company, 1905. Page 488.

- The Long Island Historical Journal, volumes 5-6 (1992). Page 150.

- Onderdonck Jr., Henry. History of the First Reformed Dutch Church of Jamaica, L.I. The Consistory, 1884. Page 132-133.

- Cook, Adrian. The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1974. Page 77.

- Brooklyn Public Library. “Brooklyn and the New York City Draft Riots”.

- Cook, Adrian. The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1974. Pages 77-95, 151, 172.

- Wellman, Judith. Brooklyn’s Promised Land: The Free Black Community of Weeksville, New York. New York: New York University Press, 2014. Pages 116-117; Gale Academic Onefile. “A fair and open field: the responses of black New Yorkers to the Draft Riots”.

- Pelletreau, William Smith. A History of Long Island, Volume II. New York: Lewis Publishing Company, 1905. Page 488.

Bibliography

Books

Cook, Adrian. The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1974.

Journals of the Continental Congress, volume 7 – January 1 to May 21, 1777. Page 262.

https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=lljc&fileName=007/lljc007.db&recNum=260&itemLink=r%3Fammem%2Fhlaw%3A%40field%28DOCID%2B%40lit%28jc0071%29%29%230070001&linkText=1.

Onderdonck Jr., Henry. History of the First Reformed Dutch Church of Jamaica, L.I. The Consistory, 1884.

Pelletreau, William Smith. A History of Long Island, Volume II. New York: Lewis Publishing Company, 1905.

Roemer, Brevet-Major Jacob. Reminiscences of the War of Rebellion, 1861-1865. Flushing: The Estate of Jacob Roemer, 1897.

Watkins, Sam. Co. Aytch: A Confederate Memoir of the Civil War. New York: Touchstone, 2003.

Wellman, Judith. Brooklyn’s Promised Land: The Free Black Community of Weeksville, New York. New York: New York University Press, 2014.

Williams, David. Rich Man’s War: Class, Caste, and Confederate Defeat in the Lower Chattahoochee Valley. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011.

Websites

American Battlefield Trust. “Evidence for The Unpopular Mr. Lincoln: The People at the Polls 1860-1864”.

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/evidence-unpopular-mr-lincoln.

Brooklyn Public Library. “Brooklyn and the New York City Draft Riots” (July 14, 2010).

https://www.bklynlibrary.org/blog/2010/07/14/brooklyn-and-new-york.

Gale Academic Onefile. “A fair and open field: the responses of black New Yorkers to the Draft Riots”, by Kevin McGruder (July 2013).

https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA339255270&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=03642437&p=AONE&sw=w&userGroupName=nysl_oweb&isGeoAuthType=true&aty=geo.

Random Thoughts on History. “Sam Watkins and His Stake in Slavery”, by Tim Talbott (June 29, 2015).

http://randomthoughtsonhistory.blogspot.com/2015/06/sam-watkins-and-his-stake-in-slavery.html.

Yale Macmillan Center. “An Act for enrolling and calling out the national Forces”.

https://glc.yale.edu/act-enrolling-and-calling-out-national-forces.

Videos

YouTube. Atun-Shei Films. “Was it REALLY the WAR of NORTHERN AGGRESSION?!?!?!” (April 28, 2020).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lac-8tTuyhs&list=PLwCiRao53J1y_gqJJOH6Rcgpb-vaW9wF0&index=4.

Categories: History, Uncategorized

Leave a comment