Strophodus was a 10 foot long hybodont shark which specialized in eating shellfish. It appeared during the early Jurassic Period and went extinct during the early Cretaceous Period, making it one of the longest-lived shark genera in the fossil record.

The hybodonts were a primitive group of sharks which first appeared at the end of the Devonian Period about 361 million years ago and lasted until the end of the Cretaceous Period 66 million years ago (Stumpf et al 2021). There were hundreds of species within this group, most adapted to saltwater, but a few were able to survive in brackish or freshwater.

One genus of hybodont shark was Strophodus, which was named by the Swiss ichthyologist Louis Agassiz in 1838 (Agassiz 1833-1843, pages 28, 36-38). The name Strophodus means “twisted tooth” in ancient Greek (στροφος, strophos = “twisted”; ὀδούς, odous, Latinized to odus = “tooth”), which is a very peculiar name considering that its teeth aren’t twisted – they’re short, rounded, and thick, but more about that later.

The genus Strophodus was around for a long time. The oldest confirmed species, S. smithwoodwardi, is found in Switzerland within rocks dated to the Toarcian Stage of the early Jurassic Period, 184-174 MYA. However, teeth which are ascribed to Strophodus have been found in Switzerland within rock layers dated much earlier than that, to either the Anisian or Ladinian Stage of the middle of the Triassic Period somewhere between 247-237 MYA. The youngest confirmed species is S. rebecae of Colombia, from the Valanginian and Hauterivian Stages of the early Cretaceous Period 139-126 MYA. Fossil teeth which might belong to Strophodus have been found in Europe within rocks dated to the Albian Stage of the middle Cretaceous Period 113-100 MYA, but their identity isn’t certain (Carrillo-Briceño et al 2022: e13496; Stumpf et al 2023). If the teeth from the Jurassic Toarcian and the Cretaceous Albian really do belong to Strophodus, then this would mean that Strophodus existed for approximately 130 million years! It must have been a phenomenally successful animal to have lived on Earth for so long.

Like all hybodont sharks, Strophodus had a rigid bony spine on the front edge of the dorsal fins, which served as the anchor for the dorsal fin and kept the fin’s upright shape. Unlike the dorsal spines of other hybodonts which were scythe-shaped, those belonging to Strophodus were straight except for the tip, which were slightly curved backwards. The surface of the spines were covered in many small bumps, and the rear edge of the distal end of each spine had a row of downwards pointing tooth-like structures. Based upon the size of its dorsal spines, and comparing them with the dorsal spines of other hybodont sharks which are known from complete or nearly-complete skeletal fossils, Strophodus measured 10 feet long, making it one of the larger genera of hybodont sharks (Stumpf et al 2021; Stumpf et al 2023).

The genus Strophodus is divided into fourteen species, most of which are found in middle Jurassic deposits in Europe, along with a few others from India. Because very few body fossils of this animal have been found, the differentiation of species is largely based upon subtle differences in the shape of the teeth. As with most prehistoric sharks, the best evidence that we have of this animal are fossilized teeth. Like many members of the hybodont family Acrodontidae, Strophodus had rows of thick rounded teeth designed for cracking open hard shells. There were five to six rows of thick rounded teeth on each side of the front of its upper jaw, and another series of five to six rows in the middle of the front of its lower jaw – the lower jaw neatly slotted into the upper jaw like a nutcracker. Strophodus likely had very large jaw muscles to crunch through the hard shells of ammonites or possibly even sea turtles, giving it a very beefy muscular profile. Due to the abundance of ammonites and other shellfish, taking advantage of such an abundant food resource would be very advantageous. Evidently Strophodus was very good at it, reaching sizes comparable to a modern-day Bull Shark. Furthermore, just like a Bull Shark, there’s evidence from isotopic analysis of its teeth that Strophodus was able to survive in brackish water, and might have even been able to dwell in freshwater for limited periods of time (Leuzinger et al 2015; Stumpf et al 2023). Fossil remains of Strophodus‘ close relative Acrodus are also frequently found in freshwater deposits, which means that all members of the family Acrodontidae were likely capable of living in both saltwater and freshwater (Cuny et al 2014).

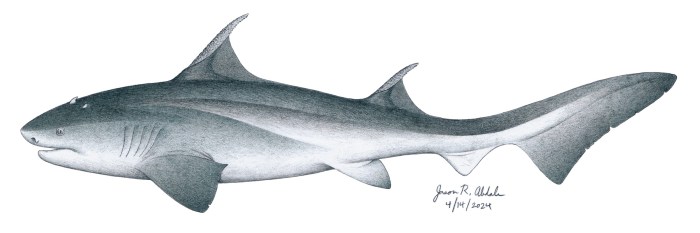

Strophodus. © Jason R. Abdale (April 14, 2024).

If you enjoy these drawings and articles, please click the “like” button, and leave a comment to let me know what you think. Subscribe to this blog if you wish to be immediately informed whenever a new post is published. Kindly check out my pages on Redbubble and Fine Art America if you want to purchase merch of my artwork.

Bibliography

Agassiz, Louis. Recherches sur les Poissons Fossiles, Volume 1. Neuchatel: Petitpierre, 1833-1843.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/23069#page/7/mode/1up.

Carrillo-Briceño, Jorge D.; Cadena, Edwin-Alberto (2022). “A new hybodontiform shark (Strophodus Agassiz 1838) from the Lower Cretaceous (Valanginian-Hauterivian) of Colombia”. PeerJ, volume 10: e13496 (June 2, 2022).

https://peerj.com/articles/13496/.

Cuny, Gilles; Liard, Romain; Deesri, Uthumporn; Liard, Tida; Khamha, Suchada; Suteethorn, Varavudh (2014). “Shark faunas from the Late Jurassic—Early Cretaceous of northeastern Thailand”. Paläontologische Zeitschrift, volume 88 (December 3, 2014). Pages 309-328.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12542-013-0206-0.

Leuzinger, L.; Kocsis, L.; Billon-Bruyat, J-P.; Spezzaferri, S.; Vennemann, T. (2015). “Stable isotope study of a new chondrichthyan fauna (Kimmeridgian, Porrentruy, Swiss Jura): An unusual freshwater-influenced isotopic composition for the hybodont shark Asteracanthus”. Biogeosciences, volume 12, issue 23 (December 2015). Pages 6,945-6,954.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286372964_Stable_isotope_study_of_a_new_chondrichthyan_fauna_Kimmeridgian_Porrentruy_Swiss_Jura_an_unusual_freshwater-influenced_isotopic_composition_for_the_hybodont_shark_Asteracanthus.

Stumpf, Sebastian; Kettler, Christoph; Kindlimann, René; Cuny, Gilles; Kriwet, Jürgen (2023). “The oldest Gondwanan record of the extinct durophagous hybodontiform chondrichthyan, Strophodus from the Bajocian of Morocco”. Swiss Journal of Palaeontology, volume 142, number 5 (April 25, 2023).

https://sjpp.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s13358-023-00270-w.

Stumpf, Sebastian; López-Romero, Faviel A.; Kindlimann, René; Lacombat, Frederic; Pohl, Burkhard; Kriwet, Jürgen (2021). “A unique hybodontiform skeleton provides novel insights into Mesozoic chondrichthyan life”. Papers in Palaeontology, volume 7, issue 3 (August 2021). Pages 1,479-1,505.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/spp2.1350.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment