Introduction

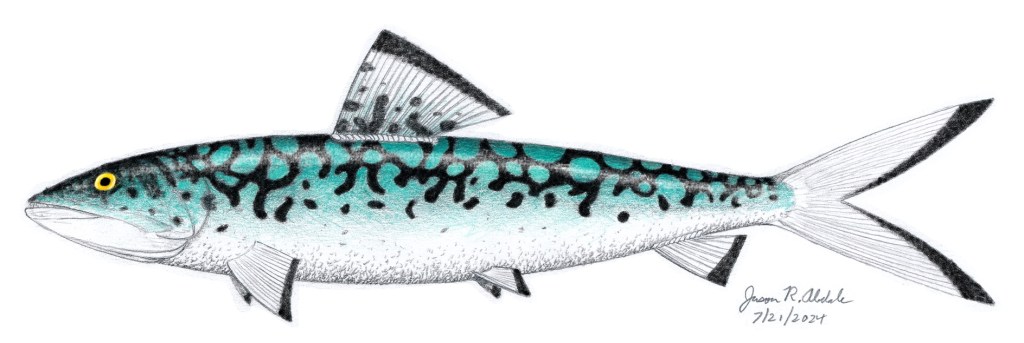

Apsopelix and Pelecorapis were two genera of closely-related prehistoric saltwater fish which lived during the middle to late Cretaceous Period. Fossils of Apsopelix have been found in England, France, and in the American states of Montana, South Dakota, Colorado, Kansas, and Texas within rocks dated to the middle and late Cretaceous Period 95-66 million years ago. Its close relative Pelecorapis seems to have been exclusively North American, its fossils being found only within Kansas, and lived within the shallow sea which once covered the center of North America during the middle Cretaceous 95 million years ago. Both Apsopelix and Pelecorapis were similar in shape to a modern-day mackerel except that these prehistoric fish had numerous small bony scutes positioned at the base of their fins. Both species belonged to the prehistoric fish family Crossognathidae, and both lived at approximately the same time and in some cases in the same locations.

All of these similarities have led paleontologists to claim that Apsopelix and Pelecorapis are actually the same animal, and since Apsopelix was named first, then this name would take priority and the name Pelecorapis would be discarded. But is this true? In this article, I will carefully examine all of the evidence and I’ll see if I can answer this question.

History of Discoveries

During the 1800s, a man named Sir Philip Egerton discovered a fossil fish in Kent, England. It was believed to belong to a British species of Calamopleurus, whose fossils were previously known only from Brazil. In 1850, Frederick Dixon named it Calamopleurus anglicus (Dixon 1850, pages 375-376).

On the other side of the Atlantic, another similar-looking fish fossil was found at the “Bunker Hill Station” along the Pacific Railroad line in Kansas. In 1871, the famous American paleontologist Edward D. Cope, who is most well-known for his role in the “Bone Wars”, named this specimen Apsopelix sauriformis (collection ID code: AMNH 1602). Cope didn’t include any measurements in his description of this fossil fish. The size of the animal was described in its official formal description as “about that of a one-pound brook trout” (Cope 1871, pages 423-424), as if the author assumed that everyone would automatically know exactly how big that is. According to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, a one-pound brook trout typically measures 13 and a half inches long (“Use A Ruler To Weigh Your Fish”). The fossil was stated to have come from the Benton Group (Cope and Yarrow 1875, page 702). The name Apsopelix literally means “arched basin” in ancient Greek, and likely refers to the shape of the animal’s pelvic region.

In 1875, it was suggested that the English specimen which Frederick Dixon referred to as Calamopleurus might actually be Apsopelix (Cope and Yarrow 1875, page 702). As a result, the species Calamopleurus anglicus (named in 1850) and Apsopelix sauriformis (named in 1871) were conflated to form a new name – Apsopelix anglicus. Since the species name anglicus was given in the scientific literature first, this replaced the species name sauriformis.

Other specimens ascribed to Apsopelix sauriformis / anglicus were discovered, one of which attained a length of 17.5 inches (Jordan 1924, page 230). The following specimens of Apsopelix have been recovered (note that I’m not sure if this is a complete list) (Teller-Marshall and Bardack 1978, page 4):

- The holotype specimen from “Bunker Hill Station, Kansas (collection ID code: AMNH 1602). Fencepost Limestone Member, Benton Shale. Cenomanian Stage, middle Cretaceous Period.

- Nearly whole fish specimen, lacking tail, from western Kansas (collection ID code: KU 18). Fencepost Limestone Member, Benton Shale. Cenomanian Stage, middle Cretaceous Period.

- Multiple specimens from western Kansas (collection ID codes: SMM 7598; KU 309; KU 310; KU 318; KU 519). Smokey Hill Chalk Member, Niobrara Formation.

- Head and front of body from one mile northeast of Scotsville, Mitchell County, Kansas (collection ID code: KU 882). Either Jetmore Limestone Member or Lincoln Limestone Member, Greenhorn Formation.

- Head and front of body from Dallas County, Texas (collection ID code: FMNH PF7463). Eagle Ford Formation.

- Back part of skull and front of body from approximately 1.75 miles east of Coupland, Williamson County, Texas (collection ID code: UT 848). Horizon uncertain, dated to upper Cretaceous.

- Whole fish specimen from Savoy Pit, located approximately four miles southeast of Savoy, Fannin County, Texas (collection ID code: UT 31051-7). Ector Member, Austin Group.

- Whole fish specimen from Grayson County, Texas (collection ID code: UT 40092-6). Lower part of Austin Chalk.

- Head and front of body from Chamberlain, South Dakota (collection ID code: USNM 16725). Pierre Shale, Campanian Stage, late Cretaceous Period.

- Head from Brule County, South Dakota (collection ID code: USNM V23193). Pierre Shale, Campanian Stage, late Cretaceous Period.

- Front third of individual, from Hughes County, South Dakota (collection ID code: SDSM 77482). Upper part of the DeGrey Formation, Pierre Shale (Parris et al 2007, page 104).

- Partial body specimen from Fort Pierre, Montana (collection ID code: AMNH 2437). Pierre Shale, late Cretaceous Period. Note that this specimen was originally classified in 1877 as the holotype specimen of Pelecorapis berycinus, as described further on.

- A single specimen from Vallentigny, Aube Department, France. Albian Stage, middle Cretaceous (Wenz, Sylvie (1965). “Les poissons Albiens de Vallentigny (Aube)”. Annales de Paléontologie Vertébrés, volume 51 (1965). Pages 3-23).

- A specimen from Folkstone, England (collection ID code: NHMUK PV P9890). Gault Clay Formation, Cenomanian or Turonian Stage, middle-to-late Cretaceous Period (Schwarzhans et al 2018, pages 514, 522).

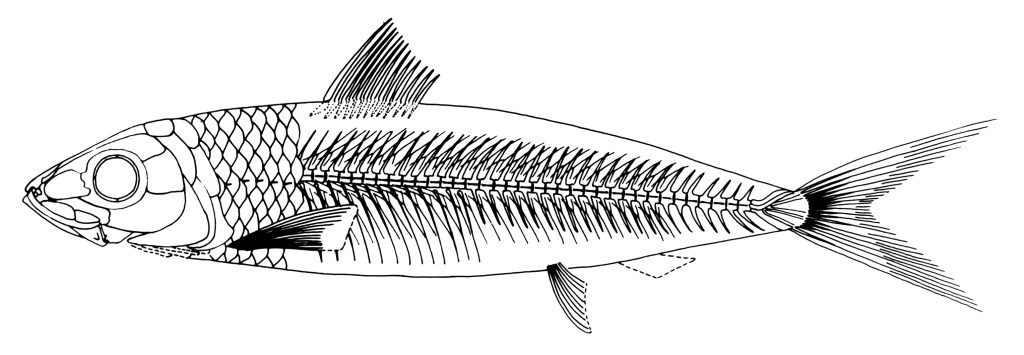

Apsopelix possessed ten to twelve rows of cycloid-shaped scales on each side of its body. Pectoral fins had 15 rays, pelvic fins had 12 rays, and the dorsal fin had 13 rays. The anatomy of Apsopelix, in particular its extremely tiny teeth and its long gill rakers, indicates that it fed primarily on microscopic plankton (Teller-Marshall and Bardack 1978, pages 3, 5).

Skeleton of Apsopelix anglicus. Teller-Marshall, Susan; Bardack, David (1978). “The Morphology and Relationships of the Cretaceous Teleost Apsopelix“. Fieldiana: Geology, volume 41, issue 1 (September 29, 1978). Page 24.

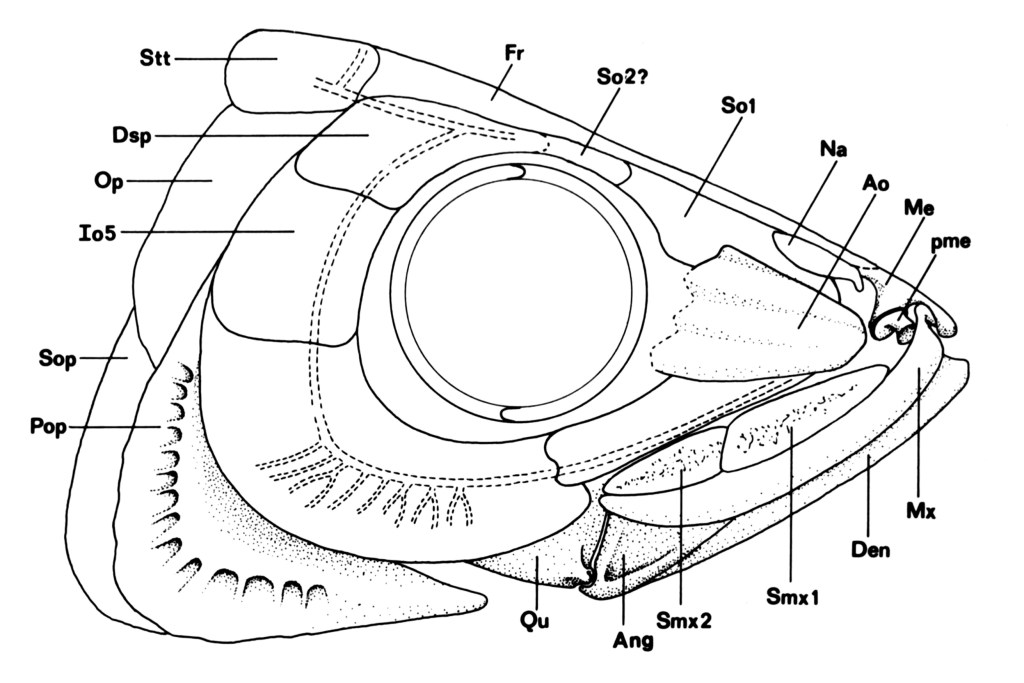

Skull of Apsopelix anglicus. Teller-Marshall, Susan; Bardack, David (1978). “The Morphology and Relationships of the Cretaceous Teleost Apsopelix“. Fieldiana: Geology, volume 41, issue 1 (September 29, 1978). Page 19.

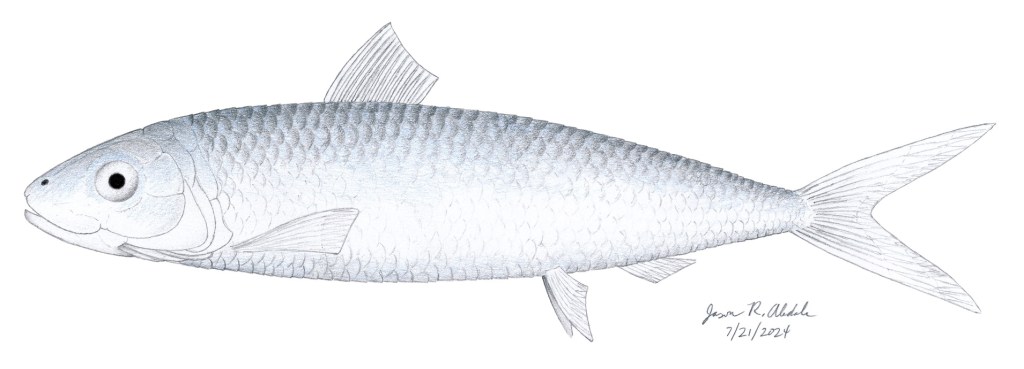

Reconstruction of Apsopelix anglicus. © Jason R. Abdale (July 21, 2024).

At around the same time that fossils of Apsopelix were being found within the American West, another fish fossil was discovered by Professor Benjamin F. Mudge, the Kansas state geologist, within a layer of grey clay located two miles west of the town of Sibley, Kansas. The rocks here belong to the “Fencepost Limestone” of the Benton Shale, which is dated to the Cenomanian Stage of the middle Cretaceous Period about 95 MYA. In 1874, Edward D. Cope officially named this specimen Pelecorapis varius. Several more specimens of this animal were found afterwards, all known from Kansas. The body length for Pelecorapis varius, not including the tail fin, is about 2 feet; it measured 30.5 inches long in total. Its body was covered in rows of small ctenoid-shaped scales (round with a toothed or saw-like edge) usually measuring just 3 mm in diameter, and there were small bony scutes positioned at the base of the dorsal, pectoral, pelvic, and anal fins (Cope 1874, page 39; Cragin 1901, pages 31-34; Cockerell 1919, pages 171, 187).

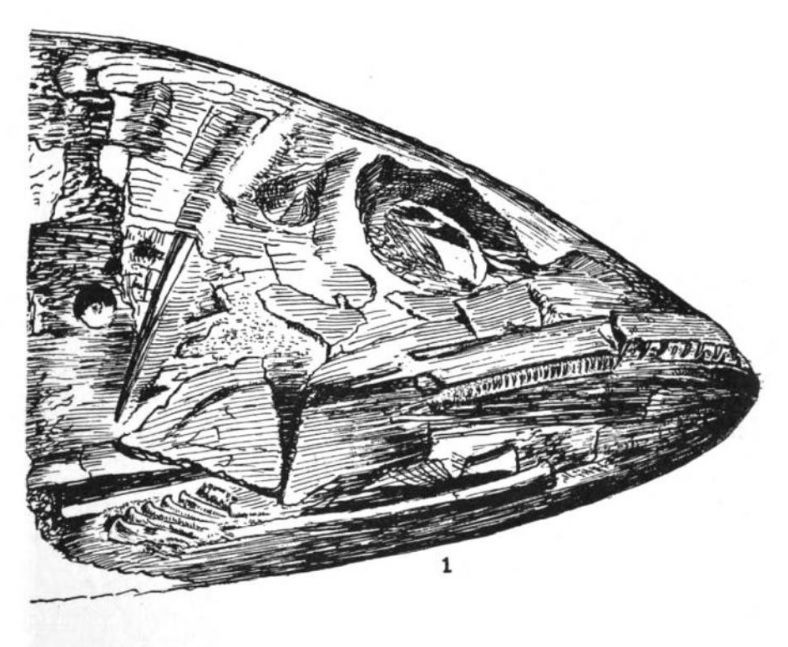

Right lateral view of the head of Pelecorapis varius. Illustrated by Dr. J. C. Shedd. Cragin, F. W. (1901). “A Study of Some Teleosts from the Russell Substage of the Platte Cretaceous Series”. Colorado College Studies, volume IX (May 1901). Plate II, Figure 1, page 40.

In 1877, Edward D. Cope wrote a follow-up article stating that he had mistakenly mis-spelled the name as Pelecorapis instead of Pelycorapis, which is what he had intended. However, according to the rules of naming new taxa, that original name is the one which stays, even though it is mis-spelled. Cope stated that the name Pelecorapis is derived from the ancient Greek πελύξ (pelyx) meaning “pelvis” and ῥαπίς (rhapís), which he doesn’t translate (Cope 1877, page 587). It’s wrong. Pelyx is not the ancient Greek word for “pelvis”; the ancient Greek word pelyx means “basin”, which is also what the Latin word pelvis translates to. The ancient Greek word ῥαπίς (rhapís) means “needle” (note that rhapis is an uncommonly-used word for “needle”, as the word βελόνη (belone) is used more often). So the name would mean…”basin needle”…but that makes no sense. According to Cope’s earlier 1874 article, the justification for this name (although he doesn’t explicitly say so) comes from the structure of the animal’s pelvic region: “The pubic bones consist of two antero-posterior plates, in contact on the middle line. The anterior portion projects to a median angle, and there is an angular projection of the lateral border. From the angle formed by these borders, a long cylindrical rod projects forward” (Cope 1874, page 39). It’s a very clumsy and awkward name given its translation and context. However, the name “Iskhioseskhimabelona”, which literally means “needle-shaped hip” (ισχίο σε σχήμα βελόνας), while much more accurate descriptively, is also much more of a mouthful to pronounce!

F. W. Cragin’s anatomical description of Pelecorapis varius is as follows: The body length, not including the tail fin, is about 2 feet, and measures 30.5 inches long in total. The maximum height of the body is 121 mm. The dorsal fin is placed in the middle of the back, and possesses twenty rays, the front rays being taller than the rear ones, and all placed close together; the change in height being gradual. The length of the first/longest ray of the dorsal fin is 95 mm. The length of the base of the dorsal fin is 80 mm. The base of the dorsal fin is attached on either side by a series of large smooth bony rhomboid-shaped overlapping scutes, the longer sides being forward and downward; there is one scute on either side for each dorsal ray. The upper edge of each scute abuts against the base of each dorsal ray. The distance from the tip of the snout to the beginning of the pelvic fin is 351 mm. The distance between the first ray of the pectoral fin and the first ray of the pelvic fin is 190-195 mm. The pectoral fin is elongate and triangular, reaching almost halfway to the base of the pelvic fin. Each pectoral fin has sixteen rays. The length of the first/longest ray of the pelvic fin is 52 mm. The pelvic fin is situated directly behind the dorsal fin, consisting of one large thick leading ray, and twelve or thirteen soft flexible rays behind. Both the pectoral and pelvic fins are subtended on the ventral side only by a series of scutes similar in shape to those seen on the back. The anterior portion of the base of the anal fin is bounded on either side by scutes. The lateral line is situated high up on the anterior portion of the sides in front of the dorsal fin. Small ctenoid-shaped scales are arranged in about 50 longitudinal rows; the anterior scales are larger than the posterior scales, the largest scales measuring 6 mm in diameter, the smallest measuring just 1.5 mm in diameter; the majority of body scales measure 3 mm in diameter; the posterior edge of the scales has a toothed edge (Cragin 1901, pages 31-34).

Reconstruction of Pelecorapis varius. © Jason R. Abdale (July 21, 2024).

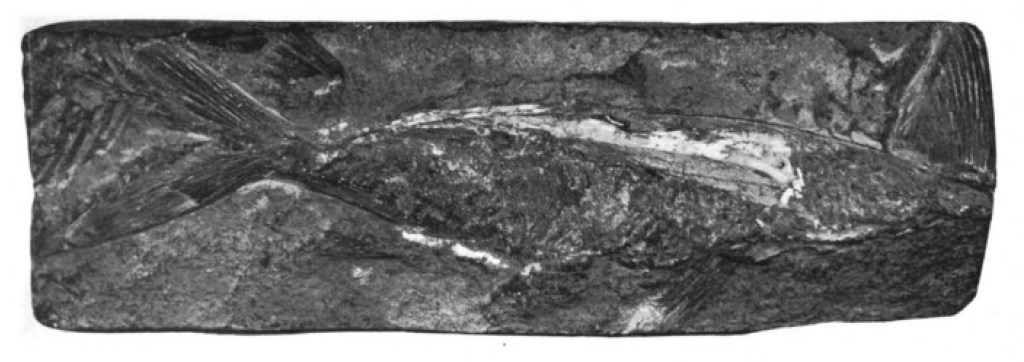

Three years after naming Pelecorapis varius, Edward Cope named another species, Pelecorapis berycinus. This specimen was found at Fort Pierre, Montana within the Pierre Shale. Consists of a chalcedonized section of the trunk with preserved scales (collection ID code: AMNH 2437) (Cope 1877, pages 586-588; Hay 1902, page 399; Hussakof 1908, page 87). The Pierre Shale, which was originally named as the “Fort Pierre Group” by the geologists F. B. Meek and Ferdinand V. Hayden in 1862, dates to the Campanian and Maastrichtian Stages of the late Cretaceous Period, 83-66 MYA (Meek and Hayden 1862, pages 419, 424; Reeside Jr. 1944).

Holotype specimen of Pelecorapis berycinus. This species was later declared to have been mis-identified, and actually belonged to Apsopelix anglicus. Hussakof, Louis (1908). “Catalogue of the Type and Figured Specimens of Fossil Vertebrates in the American Museum of Natural History. Part I: Fishes”. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, volume 25 (June 1908). Page 86.

In 1901, F. W. Cragin named the species Pelecorapis microlepis from a single incomplete specimen found within the Fencepost Limestone (the same strata that Pelecorapis varius was discovered in) near Bazine, Kansas which preserved only the rear three-fourths of the body. The body is smaller and proportionally more elongate than P. varius. Maximum body height of 60 mm. The scales are VERY tiny, measuring scarcely 1 mm in diameter, and are arranged in 60 longitudinal rows instead of 50. The distance from the leading edge of the pectoral fin to the tip of the tail is 338 mm. The distance from the leading edge of the pectoral fin to the beginning of the anal scutes is 173 mm. The upper lobe of the tail fin measures 90 mm from the tip to the fork between the upper and lower lobe. The midpoint of the upper lobe measures 19 mm wide (Cragin 1901, pages 35-37).

Type specimen of Pelecorapis microlepis. Photograph by Albert A. Blackman. Cragin, F. W. (1901). “A Study of Some Teleosts from the Russell Substage of the Platte Cretaceous Series”. Colorado College Studies, volume IX (May 1901). Plate III, page 41.

Classification Problems

Arthur S. Woodward created the family Crossognathidae in 1901 to include the eponymous Crossognathus and its close relative Syllaemus. Woodward also tentatively placed Apsopelix, Pelecorapis, and Leptichthys within Crossognathidae. But how exactly was the family Crossognathidae defined? The anatomical features which Woodward gives on Page 348 of his study could very well be ascribed to any number of fish species (Woodward 1901, pages 348-354). Later in 1977, Patterson and Rosen diagnosed Crossognathidae as possessing “uroneurals that cover the lateral faces of the ural and first two preural centra” (Patterson and Rosen 1977, page 131).

In 1919, Theodore D. A. Cockerell proposed that Pelecorapis was likely a member of the family Crossognathidae or possibly Scombresocidae or Atherinidae, but the first option was most likely (Cockerell 1919, pages 185, 187). In 1958, David H. Dunkle (the man that the large Devonian fish Dunkleosteus is named after) stated that Pelecorapis varius was very closely related to Thrissopater intestinalis, and further posited that the former might actually be a junior synonym of the latter, although he never actually said that this was definitely the case (Dunkle 1958, pages 270-271). Thrissopater itself was later declared to be a synonym of Pachyrhizodus (Forey 1977, pages 125-204). Dunkle also stated that the species Pelecorapis berycinus, which had been found within the Pierre Shale of Montana and which had been named by Edward D. Cope in 1877, was declared to be a junior synonym of Apsopelix (Dunkle 1958, page 271). This assessment was reiterated in 1977 (Patterson and Rosen 1977, pages 131-132) and 2006 (Shimada and Fielitz 2006, page 202). I agree with this decision, as the preserved scales on the specimen of Pelecorapis berycinus are quite large, far larger than the preserved scales on either P. varius or P. microlepis. However, Patterson and Rosen stated that, while Pelecorapis berycinus was mis-identified and was actually another specimen of Apsopelix anglicus, the species Pelecorapis varius is indeed a distinct taxon (Patterson and Rosen 1977, pages 131-132).

According to Patterson and Rosen, Apsopelix “is almost identical with that of Crossognathus, differing only in having the neural and hemal spines more strongly inclined and pressed together, and in the increased hypurostegy, so that the proximal ends of the upper and lower principal rays almost meet. Apsopelix is a distinctive fish, most readily recognized by the very large scales and pelvic fins, which lie farther back than in any other teleost we know (prepelvic length equals 70 per cent of standard length in BMNH P.9184), and are supported by massive, broad pelvic bones with a strong midline symphysis. The caudal part of the vertebral column is very short, containing only 12 to 14 vertebrae out of a total of about 38-40, and the anal fin must have been very short (it is said to be absent by Woodward and Wenz, but fragments are preserved in AMNH 1602 and 8330). Crossognathus has smaller pelvics and an unmodified pelvic girdle, and the prepelvic length is about 60 percent of the standard length. There are about 35 vertebrae, with 15 caudal (excluding the ural centra). There are well-developed epipleural intermusculars in both Crossognathus and Apsopelix” (Patterson and Rosen 1977, page 132).

In 1995, Karl Albert Frickhinger stated that the genus Pelecorapis was a junior synonym of the crossognathid genus Apsopelix (Frickhinger 1995, page 1,036).

Reviewing the Evidence, and Making Conclusions

As you can see from the previous reports, there’s a lot of confusion as to whether or not Apsopelix and Pelecorapis are two separate genera or if they are one-and-the-same. Let’s look at the physical evidence from the fossils themselves:

- Apsopelix is described as having cycloid-shaped scales, while Pelecorapis is stated to have ctenoid-shaped scales (Teller-Marshall and Bardack 1978, page 5; Cragin 1901, pages 31, 36).

- Apsopelix anglicus only had 10-12 rows of scales on each side of the body (Teller-Marshall and Bardack 1978, page 5), whereas Pelecorapis varius had approximately 50 (Cragin 1901, pages 31, 33, 34).

- The scales on Pelecorapis were dramatically smaller compared to the scales of Apsopelix.

- Apsopelix and Pelecorapis had different numbers of rays to their fins.

Based upon the documentation presented, it is my judgement that:

- Pelecorapis is a valid name for a distinct genus, and it should not be declared a junior synonym of Apsopelix.

- The genus name Pelecorapis only applies to the species P. varius.

- The species Pelecorapis microlepis is likely a junior synonym of P. varius, owing to both being found within the same stratum and in the same geographic location. It’s likely that P. microlepis is simply a juvenile specimen of P. varius.

- The species Pelecorapis berycinus is a mis-identified specimen of Apsopelix anglicus.

Post-Script

If you enjoy these drawings and articles, please click the “like” button, and leave a comment to let me know what you think. Subscribe to this blog if you wish to be immediately informed whenever a new post is published. Kindly check out my pages on Redbubble and Fine Art America if you want to purchase merch of my artwork. Also, please consider becoming a patron on my Patreon page so that I can afford to purchase the art supplies and research materials that I need to keep posting art and articles onto this website. And, as always, keep your pencils sharp.

Bibliography

Books

Dixon, Frederick. The Geology and Fossils of the Tertiary and Cretaceous Formations of Sussex. London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1850.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/51324#page/9/mode/1up.

Frickhinger, Karl Albert. Fossil Atlas: Fishes. Translated by R. P. S. Jefferies. Blacksburg: Tetra Press, 1995.

Articles

Cockerell, T. D. A. (1919). “Some American Cretaceous Fish Scales, with Notes on the Classification and Distribution of Cretaceous Fishes”. U. S. Geological Survey. Shorter Contributions to General Geology, professional paper 120. Pages 165-203.

https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/0120i/report.pdf.

Cope, Edward D. (1871). “On the Fossil Reptiles and Fishes of the Cretaceous Rocks of Kansas”. In Hayden, F. V., ed. Preliminary Report of the United States Geological Survey of Wyoming and Portions of Contiguous Territories. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1871. Pages 385-424.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Preliminary_Report_of_the_United_States/_khEAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Apsopelix+1871&pg=PA423&printsec=frontcover.

Cope, Edward D. (1874). “The Vertebrata of the Cretaceous Period Found West of the Mississippi River”. Bulletin of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, no. 2 (April 9, 1874). Pages 5-48.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Pamphlets_on_Biology/MkUXAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Pelecorapis&pg=RA4-PA39&printsec=frontcover.

Cope, Edward D. (1877). “Report on the Geology of the Region of the Judith River, Montana, and on Vertebrate Fossils obtained on or near the Missouri River”. Bulletin of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, volume 3. Pages 565-598.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/98702#page/7/mode/1up.

Cope, Edward D.; Yarrow, H. C. (1875). “Chapter 6 – Report on the collections of fishes made in portions of Nevada, Utah, California, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona during the years 1872, 1873, and 1874”. In Yarrow, H. C.; Henshaw, H. W.; Cope, E. D., eds. Report upon Geographical and Geological Explorations and Surveys West of the One Hundredth Meridian, Volume 5 – Zoology. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1875. Pages 635-704.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Report_Upon_United_States_Geographical_S/Piw-DT6HPWgC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=apsopelix&pg=PA702&printsec=frontcover.

Cragin, F. W. (1901). “A Study of Some Teleosts from the Russell Substage of the Platte Cretaceous Series”. Colorado College Studies, volume IX (May 1901). Pages 25-41.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Colorado_College_Studies/95c-AAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Dunkle, David H. (1958). “Three North American Cretaceous Fishes”. Proceedings of the United States National Museum, volume 108, issue 3401 (1958). Pages 269-277.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/partpdf/7090.

Forey, Peter L. (1977). “The osteology of Notelops Woodward, Rhacolepis Agassiz, and Pachyrhizodus Dixon (Pisces: Teleostei)”. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Geology, volume 28, issue 2 (February 24, 1977). Pages 125-204.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/2251874#page/151/mode/1up.

Hay, Oliver Perry (1902). “Bibliography and Catalogue of the Fossil Vertebrata of North America”. Bulletin of the United States Geological Survey, number 179. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1902. Pages 7-868.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Bulletin_of_the_United_States_Geological/hyIMAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Pelecorapis+berycinus+Pierre&pg=RA1-PA399&printsec=frontcover.

Hussakof, Louis (1908). “Catalogue of the Type and Figured Specimens of Fossil Vertebrates in the American Museum of Natural History. Part I: Fishes”. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, volume 25 (June 1908). Pages 1-103.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Catalogue_of_the_Type_and_Figured_Specim/KzssAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Jordan, David Starr (1924). “A Collection of Fossil Fishes in the University of Kansas, from the Niobrara Formation, of the Cretaceous”. The Kansas University Science Bulletin, volume 15, issue 2 (December 1924). Pages 219-245.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Kansas_University_Science_Bulletin/-6IzAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Meek, F. B.; Hayden F. V. (1862). “Descriptions of new Lower Silurian, (Primordial), Jurassic, Cretaceous, and Tertiary Fossils, collected in Nebraska, by the Exploring Expedition under the command of Capt. Wm. F. Raynolds, U.S. Top. Engrs.; with some remarks on the rocks from which they were obtained”. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, volume 13 (1862). Pages 415-447.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044107306102&seq=1.

Parris, David C.; Grandstaff, Barbara Smith; Gallagher, William B. (2007). “Fossil fish from the Pierre Shale Group (Late Cretaceous): Clarifying the biostratigraphic record”. The Geological Society of America, special paper 427 (January 2007). Pages 99-109.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287691272_Fossil_fish_from_the_Pierre_Shale_Group_Late_Cretaceous_Clarifying_the_biostratigraphic_record.

Patterson, Colin; Rosen, Don Eric (1977). “Review of ichthyodectiform and other Mesozoic teleost fishes and the theory and practice of classifying fossils”. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, volume 158, article 2 (February 23, 1977). Pages 83-172.

https://digitallibrary.amnh.org/items/c6bfdc09-7d7c-482c-9241-c805ca2567ed.

Reeside, Jr., John B. (1944). “Maps showing thickness and general character of the Cretaceous deposits in the Western Interior of the United States”. U.S. Geological Survey Oil and Gas Investigations Preliminary Map, OM-10, 1 sheet, scale 1:13,939,200.

https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/Prodesc/proddesc_5244.htm.

Schwarzhans, Werner; Beckett, Hermione T.; Schein, Jason D.; Friedman, Matt (2018). “Computed tomography scanning as a tool for linking the skeletal and otolith-based fossil records of teleost fishes”. Palaeontology, volume 61, issue 4 (July 2018). Pages 469-636.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/pala.12349.

Shimada, Kenshu; Fielitz, Christopher (2006). “Annotated Checklist of Fossil Fishes the Smoky Hill Chalk of the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) in Kansas”. In Lucas, S. G.; Sullivan, R.M., eds. Late Cretaceous Vertebrates from the Western Interior. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 35 (2006). Pages 193-213.

https://www.academia.edu/70620060/Annotated_checklist_of_fossil_fishes_from_the_Smoky_Hill_Chalk_of_the_Niobrara_Chalk_Upper_Cretaceous_in_Kansas?uc-sb-sw=21829760.

Teller-Marshall, Susan; Bardack, David (1978). “The Morphology and Relationships of the Cretaceous Teleost Apsopelix“. Fieldiana: Geology, volume 41, issue 1 (September 29, 1978). Pages 1-35.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/21643#page/9/mode/1up.

Woodward, Arthur Smith. Catalogue of the Fossil Fishes in the British Museum (Natural History), Volume 4. London: British Museum (Natural History), 1901. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/213418#page/5/mode/1up.

Websites

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. “Use A Ruler To Weigh Your Fish”.

https://dec.ny.gov/things-to-do/freshwater-fishing/learn-to-fish/tips-skills/use-ruler-to-weigh.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment