Challaia was a genus of prehistoric freshwater fish which lived in South America during the early and middle Triassic Period 240-230 million years ago. Its fossils have been found within several geological formations in western Argentina.

Challaia belonged to the extinct fish family Acrolepidae, meaning “high/tall scales”, referring to the lines of prominent ridges which decorate the scales’ outer surface (López-Arbarello et al 2006, page 255). The group Acrolepidae was named by the German geologist Hermann Aldinger in 1937 (Aldinger 1937, pages 32, 250). The acrolepids are mostly known from the Paleozoic Era; the group first appeared during the late Devonian Period around 370-365 million years ago, and persisted until the middle of the Triassic Period around 230 MYA (Paleobiology Database. “Acrolepis Agassiz 1833”; Paleontology Database. “Oryol (Devonian of Russian Federation)”). Challaia appears to have been one of the last surviving members of this group.

The first specimen of this animal was discovered during the early 1940s in San Juan Province in western Argentina within the rock layers of the Los Rastros Formation, which dates to the middle of the Triassic Period 235-234 million years ago. When it was found, it was originally classified as a species of the genus Myriolepis. This genus had been named by the British geologist Sir Philip Egerton back in 1846, but up to the 1940s, fossils of Myriolepis had only been found in Australia (Egerton 1846, pages 1-5). It would be unusual if one suddenly turned up in South America. However, since all of the continents were joined together during the Triassic Period, having a genus being present across the Southern Hemisphere was not outside the realm of possibilities. The Argentinian species Myriolepis elongata was coined in 1944 by the Spanish naturalist Angel Cabrera (Cabrera 1944, pages 569-576).

At around the same time, a fragmentary specimen (collection ID code: MCNAM-PV 49) featuring rows of ridged diamond-shaped fish scales was discovered 5 kilometers outside of the village of El Challao within Mendoza Province in western Argentina. In 1946, the Argentine paleontologist Carlos Rusconi named the genus Challaia, named after the village near where it was discovered. The species name was C. striata, named in reference to the striated texture of the scales. Rusconi dated the specimen to the Rhaetian Stage, at the very end of the Triassic Period. It was later determined to have been found within the Potrerillos Formation, dated to the middle of the Triassic 239-230 MYA (Rusconi 1946, page 148; Spaletti et al 2008, page 267; López-Arbarello et al 2010, page 265-266).

Holotype specimen of Challaia striata (collection ID code: MCNAMPV49) from El Challao, Departamento de Las Heras, Mendoza Province, Argentina. It’s likely that C. striata is another specimen of C. magna. Rusconi, Carlos (1946). “Peces triasicos de Mendoza”. Sociedad Cientifica Argentina, Anales, volume 141 (1946). Page 149.

According to López-Arbarello et al (2010), Challaia is distinguished from other acrolepid genera by possessing the following combination of features: “large maxilla with slender suborbital portion and large trapezoidal postorbital plate with large posteroventral expansion overlapping the lower jaw; preoperculum very inclined and narrow; at least one suborbital bone; numerous anteopercular bones, among them a very slender element laying on the dorsal border of the preoperculum; operculum narrowing upwards and much deeper, but narrower than suboperculum; two types of conical teeth on jaws, one type being much larger than the other one; scales ornamented with longitudinal ganoine ridges irregularly anastomosing posteriorly and not reaching the posterior margin of the scale” (López-Arbarello et al 2010, page 254).

Since the name Challaia first appeared in print in 1946, several species of this genus have been named: C. striata (1946), C. magna (1949), C. multidentata (1949), C. cacheutensis (1950), and C. elongata (2006). However, at present, only C. magna and C. elongata are regarded by paleontologists as valid (López-Arbarello et al 2010, page 255).

The species Challaia magna was named by Carlos Rusconi in 1949 (collection ID code: MCNAM-PV 2790) (Rusconi 1949-A, pages 221-230). The type specimen of this animal was found within the Cerro de Las Cabras Formation, which dates to the late Ladinian and early Carnian Stages of the Triassic Period, approximately 240-235 MYA. The specimen is missing part of the tail, but the animal is estimated to have attained a total length of 27.5 inches (70 cm) (López-Arbarello et al 2010, pages 254-255).

Holotype specimen of Challaia magna (collection ID code: MCNAM-PV 2790) from the Cerro de Las Cabras Formation within the Cuyana Basin north of the Cerro Bayo, Departamento de Las Heras, Mendoza Province, Argentina. Scale bar = 10 cm. López-Arbarello, Adriana; Rauhut, Oliver W. M.; Cerdeño, Esperanza (2010). “The Triassic fish faunas of the Cuyana Basin, Western Argentina”. Palaeontology, volume 53, issue 2 (March 16, 2010). Pages 249-276.

Skull of Challaia magna, based upon MCNAM-PV 2790. © Jason R. Abdale (July 26, 2024).

The species C. multidentata was also named by Rusconi in 1949 (collection ID code: MCNAM-PV 2792) (Rusconi 1949-B, pages 231-236). Unfortunately, that specimen has since been lost. However, based upon the description which Rusconi gave of it, it appears to have been another specimen of C. magna and therefore C. multidentata is relegated to being a “junior synonym” (López-Arbarello et al 2010, page 266).

The following year in 1950, Carlos Rusconi named the species Challaia cacheutensis (collection ID code: MCNAM-PV 768) based on some isolated rhomboid scales ornamented with 12 to 14 longitudinal ridges that had been found near the village of Cacheuta in Mendoza Province, Argentina. Like the type specimen of C. multidentata, the type specimen of C. cacheutensis has been lost. However, based upon Rusconi’s description, it’s now believed to be just another specimen of C. elongata (Rusconi 1950, pages 3-8; López-Arbarello et al 2010, page 266).

In 2006, it was determined that Myriolepis elongata was mis-identified and was actually a species of Challaia, so the name was changed to Challaia elongata. Although the specimen of C. elongata is incomplete, based upon the size of the specimen and comparing it with the anatomy of other acrolepid fish species that we know more about, Challaia elongata is estimated to have measured 30 inches long. This would make it one of the largest fish (or possibly THE largest fish) within its environment (López-Arbarello et al 2006, pages 238, 250-255).

Holotype specimen of Challaia elongata (collection ID code: MLP 44-VII-16-3) from the Los Rastros Formation within the Bermejo Basin near Agua de La Peña Creek, San Juan Province, Argentina. Scale bar = 5 cm. López-Arbarello, Adriana; Rogers, Raymond R.; Puerta, Pablo (2006). “Freshwater actinopterygians of the Los Rastros Formation (Triassic), Bermejo Basin, Argentina”. Fossil Record, volume 9, issue 2 (August 2006). Page 251.

According to López-Arbarello et al (2010), Challaia magna and Challaia elongata differ from each other in the following ways (López-Arbarello et al 2010, page 255):

- The lower jaw of C. magna is more robustly-built compared to the lower jaw of C. elongata.

- C. magna possesses 3 anteopercular bones instead of 5 which are seen in C. elongata.

- C. magna possesses a shallower anterior border of the preoperculum, which is only half the depth of the anterior portion of the post-orbital plate of the maxilla.

- C. magna’s scales are shallower than the scales of C. elongata.

- Th scales of C. magna have fewer ridges on their surface compared to the scales of C. elongata.

- The ridges on the scales of C. magna are much thicker compared to the ridges on the scales of C. elongata.

The scales of Challaia striata and C. magna are nearly identical, and it’s likely that they are the same animal (López-Arbarello et al 2006, page 255). Technically, since C. striata was named first, this name should have priority. However, it was presumably decided that the fragmentary specimen of this animal wasn’t sufficient enough to serve as the type specimen of a species, and so the type specimen of C. magna was declared to be the type specimen of the genus.

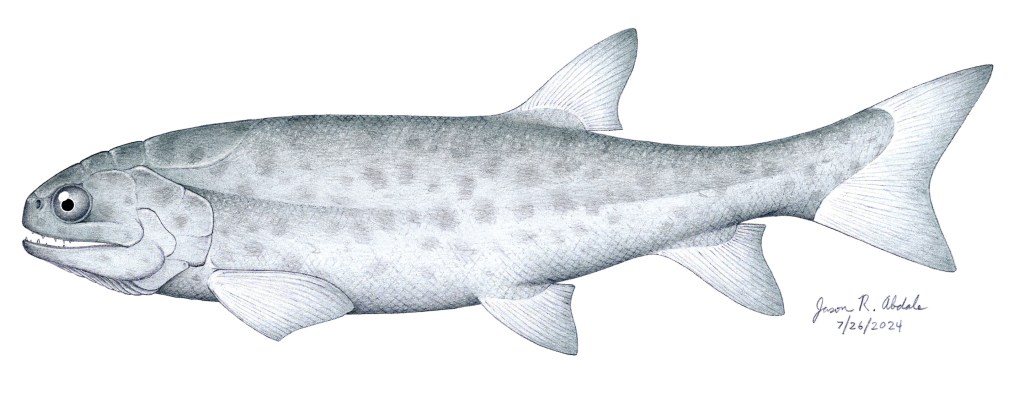

One of the most obvious features of Challaia is its large eyes. The holotype of Challaia elongata had been found within dark grey siltstone, suggesting that it lived in still or slow-moving murky muddy water (López-Arbarello et al 2006, page 241). Having unusually large eyes would be a definite advantage in such a poor-visibility environment. The eyes are also positioned very forwards on the head, and it’s possible that Challaia possessed heightened binocular vision. The numerous longitudinal ridges on its scales would help to reduce the sheen of sunlight bouncing off of the scales’ surface, very similar to how buttons on many military uniforms have a roughened bumpy texture to prevent them from having a shiny appearance and thus giving your position away to the enemy. Challaia’s teeth were also very large in proportion to its jaws, giving Challaia a formidable profile. Other fish were found within the same rocks as Challaia, such as Rastrolepis and Gualolepis, but they were only half the size of their fang-toothed neighbor, and they likely would have made a tasty snack. To protect themselves from attack, Rastrolepis was covered in rows of thick enameled scales like medieval chain-mail armor. Gualolepis had smaller thinner scales, but each one was reinforced with a thick central rib to provide increased durability. Challaia’s unusually large conical teeth might have been specially-designed to punch through the tough armored covering of these smaller fish species. All told, Challaia must have been a very impressive hunter.

However, Challaia was by no means the top predator within its Triassic underwater world. That title was reserved to the large amphibians like Promastodonsaurus and Pelorocephalus which occupied the same ecological niche that crocodiles and alligators do today.

Life reconstruction of Challaia elongata. © Jason R. Abdale (July 26, 2024).

If you enjoy these drawings and articles, please click the “like” button, and leave a comment to let me know what you think. Subscribe to this blog if you wish to be immediately informed whenever a new post is published. Kindly check out my pages on Redbubble and Fine Art America if you want to purchase merch of my artwork. Also, please consider becoming a patron on my Patreon page so that I can afford to purchase the art supplies and research materials that I need to keep posting art and articles onto this website. And, as always, keep your pencils sharp.

Bibliography

Aldinger, Hermann (1937). “Permische Ganoidfische aus Ostgrönland”. Meddelelser om Grønland, volume 102, issue 3. Pages 1-392.

Cabrera, Angel (1944). “Dos nuevos peces ganoideos del Triásico Argentino”. Notas del Museo de La Plata, Paleontologia, volume 9, issue 81 (1944). Pages 569-576.

Egerton, Sir Philip de Malpas Grey (1846). “On some Ichthyolites from New South Wales”. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, volume 20 (1846). Pages 1-5.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/111261#page/89/mode/1up.

López-Arbarello, Adriana; Rauhut, Oliver W. M.; Cerdeño, Esperanza (2010). “The Triassic fish faunas of the Cuyana Basin, Western Argentina”. Palaeontology, volume 53, issue 2 (March 16, 2010). Pages 249-276.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00931.x.

López-Arbarello, Adriana; Rogers, Raymond R.; Puerta, Pablo (2006). “Freshwater actinopterygians of the Los Rastros Formation (Triassic), Bermejo Basin, Argentina”. Fossil Record, volume 9, issue 2 (August 2006). Pages 238-258.

https://rogerslab.weebly.com/uploads/9/1/9/3/91932718/los_rastros_fish2.pdf.

Rusconi, Carlos (1946). “Peces triasicos de Mendoza”. Sociedad Cientifica Argentina, Anales, volume 141. Pages 148-153.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48954902#page/160/mode/1up.

Rusconi, Carlos (1949-A). “Sobre un pez pérmico de Mendoza”. Revista del Museo de Historia Natural de Mendoza, volume 3 (1949). Pages 221-230.

Rusconi, Carlos (1949-B). “Acerca del pez pérmico Neochallaia minor y otras especies”. Revista del Museo de Historia Natural de Mendoza, volume 3 (1949). Pages 231-236.

Rusconi, Carlos (1950). “Presencia de laberintodontes en varias regiones de Mendoza”. Revista del Museo de Historia Natural de Mendoza, volume 4 (1950). Pages 3-8.

Spaletti, L. A.; Fanning, C. M.; Rapela, C. W. (2008). “Dating the Triassic continental rift in the southern Andes: the Potrerillos Formation, Cuyo Basin, Argentina”. Geologica Acta, volume 6, issue 3 (September 2008). Pages 267-283.

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/13313765.pdf.

Paleobiology Database. “Acrolepis Agassiz 1833”. https://paleobiodb.org/classic/basicTaxonInfo?taxon_no=34964.

Paleontology Database. “Oryol (Devonian of Russian Federation)”. https://paleobiodb.org/classic/displayCollResults?taxon_no=34964&max_interval=Devonian&country=Russian%20Federation&is_real_user=1&basic=yes&type=view&match_subgenera=1.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment