Segisaurus was a 3 foot long theropod dinosaur which lived in northern Arizona during the early Jurassic Period 180 million years ago. Only one fragmentary skeleton has been found, discovered in 1933 within the Navajo Sandstone in Tsegi Canyon on the lands of the Navajo Indian Reservation. The partial nature of this skeleton makes determining its identity problematic.

In 1933, Ansel F. Hall, a naturalist working for the United States Forest Service, was conducting a survey of the area of Rainbow Bridge and Monument Valley within the Navajo Indian Reservation. On July 27, 1933, about one mile north of Keet Seel Ruin on the western side of Keet Seel Canyon, which is the name given to the northern branch of Tsegi Canyon, Robert Thomas (a member of Ansel Hall’s expedition) and Max Littlesalt (a Navajo guide from Kayenta) found a partial skeleton of a small dinosaur. The fossils were found within the Navajo Sandstone, which dates to the early Jurassic Period. It was, in fact, the first fossil vertebrate found within the Navajo Sandstone, which made it crucially important for both geology and paleontology. The specimen was quickly collected by Lloyd Lowry and Milton Wetherill (the dinosaur Dilophosaurus wetherilli is named after his uncle John). In October 1933, Milton Wetherill and Prof. Vertress Lawrence Vanderhoof of the University of California returned to the locality to collect the remaining fragments. The skeleton was sent to Charles Lewis Camp, Director of the University of California’s Museum of Paleontology, to analyze and describe (Hall 1934, page 21). In 1936, Camp named the animal Segisaurus halli, “Ansel Hall’s lizard from Tsegi Canyon” (Hall 1934, page 21; Camp 1936, page 39). The fossil is currently housed within the collections of the University of California’s Museum of Paleontology (collection ID code: UCMP 32101) (Carrano et al. 2005, page 835).

The Navajo Sandstone was believed to represent a vast desert of heaving sand dunes measuring hundreds of square miles in area (Camp 1936, page 40). Most professional papers which address the Navajo Sandstone broadly state that it dates to the early Jurassic Period, but exact dates are seldomly given. In 1989, Kevin Padian stated that the Navajo Sandstone dates to the Pliensbachian and Toarcian Stages of the early Jurassic Period (Padian 1989, page 438). In 2005, Spencer Lucas and his colleagues stated that the Navajo Sandstone dated to approximately 195-174 MYA (Lucas et al. 2005, page 100). In 2019, Judith Parrish and her colleagues stated that the beginning of the formation dates to around 200-195 MYA, but they couldn’t narrow it down further (Parrish et al. 2019, page 1,017). The general dates of approximately 200-174 MYA are concurrent with both the Moenave Formation (210-195 MYA) and the Kayenta Formation (198-180 MYA), and it also overlies the Kayenta Formation. In fact, the lower part of the Navajo Sandstone inter-fingers the upper part of the underlying Kayenta Formation (Parrish et al. 2019, page 1,015), indicating times when the desert expanded southwards and inundated the lands of the Kayenta Formation, and then retreated. This back-and-forth advance-and-retreat of the desert apparently occurred several times until the desert expanded southwards to such an extent that it swallowed up the Kayenta Formation completely.

The rock stratum that the fossil skeleton was found in was recorded by Charles Camp as 500 feet above the base of the Navajo Sandstone and 100 feet below its upper level (Camp 1936, page 39). If the Navajo Sandstone truly dates to 200-174 MYA, and if the bones of Segisaurus were found five-sixths of the way up the thickness of this formation as Charles Camp attests, this would therefore date the fossils to approximately 180 MYA. However, it is currently unknown if the locality at Tsegi Canyon where the fossils were found encompasses the full breadth of the Navajo Formation’s geologic timespan. In fact, in some parts of northern Arizona, the Navajo Sandstone can measure a whopping 750 meters thick (Lucas et al. 2005, page 96). Therefore, the date which I’ve given above needs to be taken with caution until the rock strata where the fossils were found can be scientifically tested using U-Pb dating.

The position of the bones suggests that the dinosaur was sitting down like a bird when it died. Possibly buried in a sandstorm? That was certainly the hypothesis put forward by Camp: “Apparently the animal had been covered by shifting sand before death, or soon after…The articulations of the knee and ankle joints and the position of the skeleton when found indicate an ability to squat on the sand in the manner of a sitting hen; perhaps as protection against sand blasts in storms, during sleep, and to elude enemies” (Camp 1936, pages 41, 50).

Charles Camp estimated that Segisaurus was the same size as Compsognathus – the famed chicken-sized meat-eating dinosaur from Jurassic Germany – and he even considered that the two might be related to each other. However, due to the limited information which he had on Segisaurus’ anatomy, and due to prevailing beliefs at the time about the anatomy of small theropod dinosaurs in general, Charles Camp elected to place Segisaurus into its own family which he named Segisauridae (Camp 1936, pages 39, 49-50). In the mid 1980s, it was proposed that Segisaurus was actually a relative of the famous Triassic dinosaur Coelophysis. In 1999, Paul Sereno suggested that Segisaurus may have been related to Procompsognathus due to similarities in the pelvis structure. This was confirmed by Matt Carrano and his colleagues in 2005 when a phylogenic analysis showed that Segisaurus was indeed a member of the super-family Coelophysoidea and it was very closely related to Procompsognathus (Carrano et al. 2005, pages 843-845).

The sole specimen of Segisaurus is believed to be a sub-adult (Carrano et al. 2005, page 843). If true, then Segisaurus might have grown slightly larger than the commonly-given estimate of 3 feet.

Charles Camp remarked at how unusually long the cervical ribs were, and he posited that they might have supported “a frill, fringe, or patagium extending along the sides of the neck”, like a cobra’s hood (Camp 1936, pages 42, 52). Before you dismiss this idea as fanciful, having a Draco volans-like membrane would be helpful for a desert-dwelling animal, as being able to extend the neck’s skin laterally to enlarge the surface area would enable it to dissipate excess heat the same way that an African elephant’s enlarged ear flaps do today. Such a structure could also be used to flash threat displays like a cobra when in conflict with others of its kind. However, Matt Carrano and his colleagues commented “There is certainly no compelling evidence to infer the presence of a cervical patagium in Segisaurus as Camp fancifully did; elongate cervical ribs are common in basal theropods and other archosaurs” (Carrano et al. 2005, page 837). Not gonna lie – I’m a bit disappointed about the lack of a cobra-like hood, but that’s the way it is.

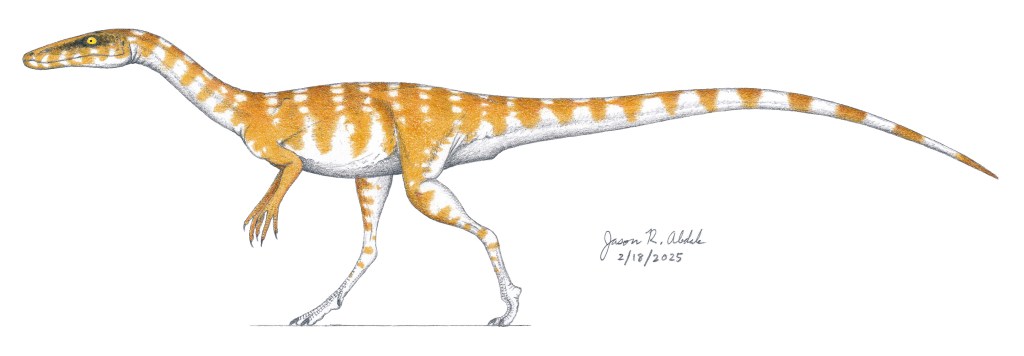

The reconstruction that you see below is based upon Procompsognathus and Podokesaurus. If Segisaurus lived in the desert, then it likely had a desert-like coloration of sandy earth tones with a lightly-colored underside.

Segisaurus halli. © Jason R. Abdale (February 18, 2025).

I truly enjoy writing my articles and drawing my art, but it’s increasingly clear that I can’t keep this up without your gracious financial assistance. Kindly check out my pages on Redbubble and Fine Art America if you want to purchase merch of my artwork. Consider buying my ancient Roman history books Four Days in September: The Battle of Teutoburg and The Great Illyrian Revolt if you or someone that you know loves that topic. Also, please consider becoming a patron on my Patreon page so that I can afford to purchase the art supplies and research materials that I need to keep posting art and articles onto this website.

Take care, and, as always, keep your pencils sharp.

Bibliography

Camp, Charles L. (1936). “A new type of small bipedal dinosaur from the Navajo sandstone of Arizona”. University of California Publications in Geological Sciences, volume 24, issue 2 (1936). Pages 39-56.

https://azmemory.azlibrary.gov/nodes/view/126405.

Carrano, Matthew T.; Hutchinson, John R.; Sampson, Scott D. (2005). “New information on Segisaurus halli, a small theropod dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of Arizona”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 25, issue 4 (December 2005). Pages 835-849.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230808545_New_information_on_Segisaurus_halli_a_small_theropod_dinosaur_from_the_Early_Jurassic_of_Arizona.

Hall, Ansel Franklin. General Report on the Rainbow Bridge-Monument Valley Expedition of 1933. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1934.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b30096&seq=5.

Lucas, Spencer G.; Heckert, Andrew B.; Tanner, Lawrence H. (2005). “Arizona’s Jurassic Fossil Vertebrates and the Age of the Glen Canyon Group”. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, issue 29 (2005). Pages 94-103.

https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=dPj5CQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA94&dq=navajo+toarcian+age&ots=C6Su_2zTyO&sig=m_nS5eFPzHSFudBmZ0nzH84IpkQ#v=onepage&q=navajo%20toarcian%20age&f=false.

Padian, Kevin (1989). “Presence of dinosaur Scelidosaurus indicates Jurassic age for the Kayenta Formation (Glen Canyon Group, northern Arizona)”. Geology, volume 17, issue 5 (May 1989). Pages 438-441.

https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/geology/article-abstract/17/5/438/204877/Presence-of-the-dinosaur-Scelidosaurus-indicates?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

Parrish, Judith Totman; Rasbury, E. T.; Chan, Marjorie A.; Hasiotis, Stephen T. (2019). “Earliest Jurassic U-Pb ages from carbonate deposits in the Navajo Sandstone, southeastern Utah, USA”. Geology, volume 47, issue 11 (September 4, 2019). Pages 1,015-1,019.

https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/geology/article/47/11/1015/573442/Earliest-Jurassic-U-Pb-ages-from-carbonate.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment