Scelidosaurus was a 12 foot long armored dinosaur which lived in Europe (and also possibly in North America) during the early Jurassic Period 200-195 million years ago.

Scelidosaurus is the most well-known European early Jurassic dinosaur because numerous specimens have been found ranging from juveniles to adults, including an extraordinary well-preserved articulated skeleton (collection ID code: BRSMG LEGL 0004) which was found in 2000. The majority of fossils have been found in southern England within the Charmouth Mudstone Formation which dates to the early Jurassic Period 200-195 MYA. Other fossils found here include the pterosaur Dimorphodon, the marine reptiles Ichthyosaurus and Plesiosaurus, and numerous species of insects, fish, and ammonites.

In the 1850s, a rock quarry owner named James Harrison found some fossils within the cliffs on Devon’s southern coast in between the towns of Charmouth and Lyme Regis. These fossils were sent to the eminent British paleontologist Sir Richard Owen to examine, and in 1859, he named it Scelidosaurus (Owen 1859, pages 150-151). Owen had intended to name the dinosaur “hind-limb lizard” in recognition of its sturdy leg bones. However, he mixed up the ancient Greek word σκέλος (skélos) “hind limb” with σκελίδα (skelída) “ribs of beef”. So, the name Scelidosaurus literally means “beef-ribs lizard”…Ugh.

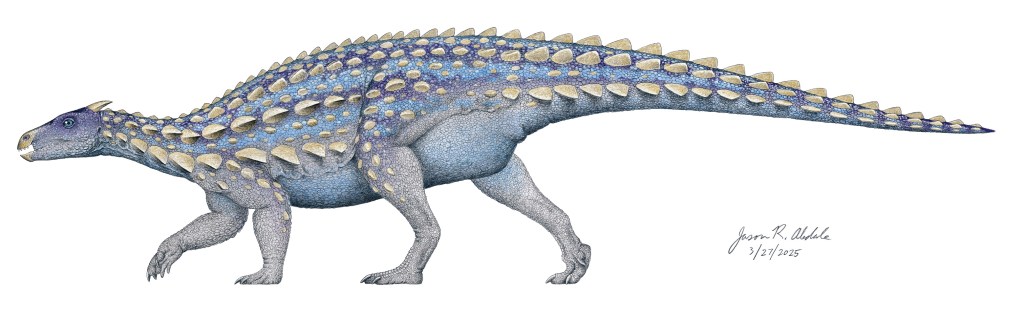

Scelidosaurus harrisoni. © Jason R. Abdale (March 27, 2025).

In addition to fossils found in southern England, at least one partial fossil consisting of the proximal end of a left femur was also found in County Antrim in northern Ireland. The fossil belonged to a scelidosaur, but at the moment it’s not clear if they belonged to Scelidosaurus specifically or to another related genus. For the moment, the remains have been classified as “cf. Scelidosaurus” which means “similar in shape to Scelidosaurus”. Nearby was also the proximal end of a left tibia belonging to an as-yet-unidentifiable meat-eating dinosaur – the scant remains make a positive identification difficult to determine. Both bone fragments were found within rocks dated to the Hettangian Stage at the beginning of the Jurassic Period, 200-195 MYA (Simms et al. 2021, pages 771-779).

Along with physical body fossils, fossilized footprints which might belong to a scelidosaur or maybe a stegosaur have been found in Hettangian-aged deposits within Corgnac-sur-l’Isle, Dordogne, France (Le Loeuff et al. 1999, pages 215-219) and the Świętokrzyskie (Holy Cross) Mountains in southeastern Poland. These footprints are placed within the ichnotaxon Moyenisauropus karaszevskii. Curiously, the footprint trackways in Poland suggested that the animal that made these footprints occasionally moved about on just its hind legs (Gierlinski 1999, pages 231-234).

During the early 1980s, several fossilized osteoderms, or “skin armor”, were discovered in numerous localities spread across the “Rock Head Quadrangle” of north-central Arizona within the rocks of the Kayenta Formation, which is dated from 198-180 MYA. These fossils were found in the lower strata of the Kayenta Formation and are dated to the upper Hettangian to lower Sinemurian Stages of the early Jurassic Period, approximately 195 MYA. At first, the paleontologist Edwin H. Colbert believed that these osteoderms belonged to a late-surviving aetosaur, and he stated as such in reports published in 1981 and 1986 (Colbert 1981; Colbert 1986). However, upon closer examination, they were found to actually belong to an armored dinosaur similar to Scelidosaurus harrisoni of early Jurassic England. In 1989, Kevin Padian ascribed these Arizona osteoderms to Scelidosaurus. These osteoderms are currently held in the collections of the Museum of Northern Arizona and the University of California Museum of Paleontology (collection ID codes: MNA V96; MNA V136; UCMP 130056 (formerly UCMP V82307)) (Padian 1989, pages 439-440). Fieldwork in northeastern Arizona carried out from 1997-2000 by the University of Texas at Austin uncovered more osteoderms which might belong to Scelidosaurus (Breeden III et al. 2021). In 2006, Martin Lockley and Gierlinski reported that Moyenisauropus footprints which were known from Poland had also been found in Arizona and Utah within the Navajo Sandstone Formation and possibly the upper part of the Kayenta Formation (Lockley and Gierlinski 2006, pages 180, 185-187). In 2014, Roman Ulansky ascribed the name Scelidosaurus arizonensis to the osteoderms found in north-central Arizona (Ulansky 2014, page 8). However in 2016, Peter Galton and Ken Carpenter stated that Scelidosaurus arizonensis was a nomen dubium, and instead elected to classify the osteoderms as “basal Thyreophora indet”. (Galton and Carpenter 2016, page 203). In a 2020 lecture, Dr. Jim Kirkland, the Utah state paleontologist, was nevertheless confident that Scelidosaurus or a close relative inhabited the American Southwest during the beginning of the Jurassic Period, saying “We don’t have a scelidosaur skeleton yet, but give us time” (“St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm: Preserving the Early Jurassic World on the Shores of Lake Dixie”).

Other examples of scelidosaurids across the world possibly include Sarcolestes of England, Emausaurus of Germany, and Bienosaurus, Tatisaurus, and Yuxisaurus of China.

I truly enjoy writing my articles and drawing my art, but it’s increasingly clear that I can’t keep this up without your gracious financial assistance. Kindly check out my pages on Redbubble and Fine Art America if you want to purchase merch of my artwork. Consider buying my ancient Roman history books Four Days in September: The Battle of Teutoburg and The Great Illyrian Revolt if you or someone that you know loves that topic. Also, please consider becoming a patron on my Patreon page so that I can afford to purchase the art supplies and research materials that I need to keep posting art and articles onto this website.

Take care, and, as always, keep your pencils sharp.

Bibliography

Breeden III, Benjamin T.; Raven, Thomas J.; Butler, Richard J.; Rowe, Timothy B.; Maidment, Susannah C. R. (2021). “The anatomy and palaeobiology of the early armoured dinosaur Scutellosaurus lawleri (Ornithischia: Thyreophora) from the Kayenta Formation (Lower Jurassic) of Arizona”. Royal Society Open Science, volume 8, issue 7 (July 21, 2021).

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.201676.

Colbert, Edwin H. (1981). “A primitive ornithischian dinosaur from the Kayenta Formation of Arizona”. Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin, volume 53 (1981). Pages 1-60.

Colbert, Edwin H. (1989). “Historical aspects of the Triassic-Jurassic boundary problem”. In Padian, Kevin, ed. The Beginning of the Age of Dinosaurs: Faunal Change across the Triassic-Jurassic Boundary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986. Pages 9-19.

Galton, Peter M.; Carpenter, Kenneth (2016). “The plated dinosaur Stegosaurus longispinus Gilmore, 1914 (Dinosauria: Ornithischia; Upper Jurassic, western USA), type species of Alcovasaurus n. gen.”. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie – Abhandlungen, volume 279, issue 2 (February 2016). Pages 185-208.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/293328275_The_plated_dinosaur_Stegosaurus_longispinus_Gilmore_1914_Dinosauria_Ornithischia_Upper_Jurassic_western_USA_type_species_of_Alcovasaurus_n_gen.

Gierlinski, Gerard Dariusz (1999). “Tracks of a large thyreophoran dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of Poland”. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, volume 44, issue 2 (June 1999). Pages 231-234.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297492832_Tracks_of_a_large_thyreophoran_dinosaur_from_the_Early_Jurassic_of_Poland/.

Le Loeuff, Jean; Lockley, Martin; Meyer, Christian; Petit, Jean-Pierre (1999). “Discovery of a thyreophoran trackway in the Hettangian of central France”. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences – Series IIA – Earth and Planetary Science, volume 328, issue 3 (February 1999). Pages 215-219.

Lockley, Martin G., Gierlinski, Gerard Dariusz (2006). “Diverse vertebrate ichnofaunas containing Anomoepus and other unusual trace fossils from the Lower Jurassic of the western United States: Implications for paleoecology and palichnostratigraphy”. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, issue 37 (2006). Pages 176-191.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/40661849_Diverse_vertebrate_ichnofaunas_containing_Anomoepus_and_other_unusual_trace_fossils_from_the_Lower_Jurassic_of_the_western_United_States_Implications_for_paleoecology_and_palichnostratigraphy.

Owen, Richard (1859). “Palaeontology”. In Encyclopædia Britannica, 8th Edition, Volume 17. Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, 1859.

https://digital.nls.uk/encyclopaedia-britannica/archive/193819046.

Padian, Kevin (1989). “Presence of dinosaur Scelidosaurus indicates Jurassic age for the Kayenta Formation (Glen Canyon Group, northern Arizona)”. Geology, volume 17, issue 5 (May 1989). Pages 438-441.

https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/geology/article-abstract/17/5/438/204877/Presence-of-the-dinosaur-Scelidosaurus-indicates?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

Simms, Michael J.; Smyth, Robert S. H.; Martiall, David M.; Collins, Patrick C.; Byrne, Roger (2021). “First dinosaur remains from Ireland”. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, volume 132, issue 6 (December 2021). Pages 771-779.

Ulansky, Roman E. (2014). “Evolution of the stegosaurs (Dinosauria; Ornithischia)”. Dinologia. Pages 1-35 [in Russian].

https://dinoweb.narod.ru/Ulansky_2014_Stegosaurs_evolution.pdf.

YouTube. Utah Friends of Paleontology. “Jim Kirkland St. George Dinosaur Discovery Talk – ‘St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm: Preserving the Early Jurassic World on the Shores of Lake Dixie’” (March 14, 2020). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ngjvqJWwZI. Accessed on March 25, 2022.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment