Muraenosaurus, “the moray eel lizard”, was a medium-sized plesiosaur which lived in the sea which once covered southern England and northern France during the middle of the Jurassic Period 165-164 million years ago.

In the 19th Century, a partial skeleton of a plesiosaur (collection ID code: BMNH R.2421) (Andrews 1910, page 78) was found within the lower part of the Oxford Clay within the district of Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, England (Seeley 1874, page 197). The Oxford Clay Formation is a geological formation found throughout much of southern England which dates to the middle of the Jurassic Period 165-160 MYA. This formation is divided into three units called “members”: the lower Peterborough Member, the middle Stewartby Member, and the upper Weymouth Member (“Oxford Clay Formation”). The fossils consisted of a partial skull, 79 vertebrae (44 cervical, 3 pectoral, 20 dorsal, 4 sacral, and 8 caudal), coracoids, scapulae, pelvic bones, and front and hind flippers. They were discovered, excavated, and prepared by Charles Edward Leeds, Esquire of Exeter College and his brother Alfred N. Leeds. In 1874, the British paleontologist Harry Seeley officially named it Muraenosaurus leedsi in honor of the two Leeds brothers who found it (Seeley 1874, pages 197-208).

The nearly-complete skeleton which was found in Huntingdon by the two Leeds brothers was designated as the holotype specimen for Muraenosaurus leedsi. Since its discovery, over a dozen more specimens have been found in southern England and northern France (Evans 1999, pages 191, 193-194; “Muraenosaurus”). Unfortunately, none of these specimens were complete. Particularly troubling is the fact that we have yet to find a complete tail. David S. Brown estimated in 1981 that Muraenosaurus leedsi measured somewhere between 14.76-17 feet (4.5-5.2 meters) long (Brown 1981, page 284).

Although Muraenosaurus seems to have been the same overall length as its contemporary Cryptoclidus, both of them measuring around 15 feet long, their physical proportions were very different to each other. The combination of a small skull and long neck made Harry Seeley suspect that Muraenosaurus was an early member of the plesiosaur family Elasmosauridae (Seeley 1892, page 134). Then in 2001, Frank Robin O’Keefe argued that Muraenosaurus was actually a cryptoclidid (O’Keefe 2001, page 20). However, Muraenosaurus had a much longer neck in proportion to body size compared to its cousin Cryptoclidus. Muraenosaurus’ vertebrae also had different proportions (Andrews 1910, pages 92-105; Brown 1981, page 289), and its flippers were narrower and pointier than those seen in Cryptoclidus (Andrews 1910, page 111).

Skeleton of Muraenosaurus leedsi. Illustration from Andrews (1910), page 118.

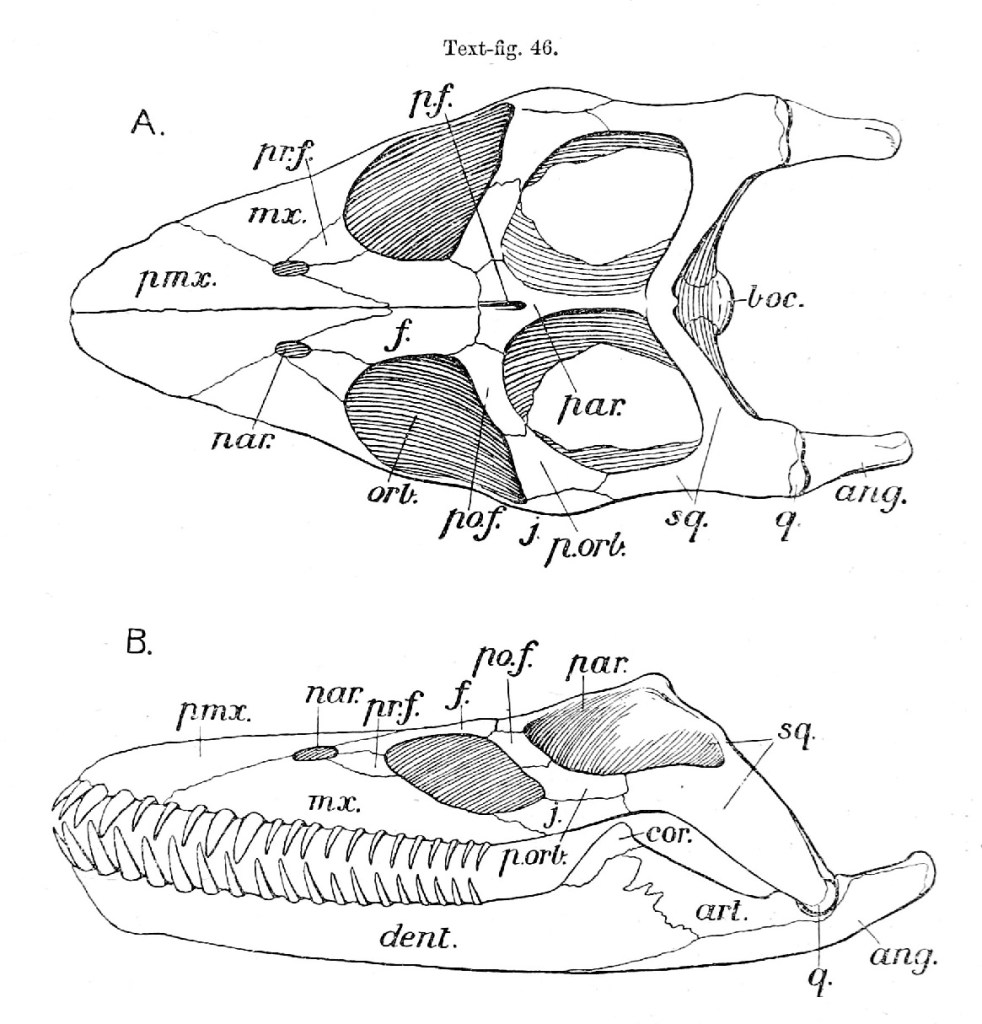

Skull of Muraenosaurus leedsi. Illustration from Andrews (1910), page 85.

Charles W. Andrews’ 1910 drawings of Muraenosaurus’ skeleton and skull were reproduced in numerous academic and popular publications on prehistoric life for decades, and they came to define the archetypal plesiosaur shape. Then in 1999, the skull of Muraenosaurus leedsi was re-examined, and it was shown that it wasn’t as flat as Charles W. Andrews had reconstructed it. The skull was more triangular in profile, with larger eye sockets, the eyes themselves being more forward-facing, and the jaws would have had more powerful muscles giving it a stronger bite. Then again, the reason why Andrews reconstructed Muraenosaurus with a flat head was because the skull had been subjected to immense pressure, making the skull appear flatter than it actually had been in life (Evans 1999, pages 191-196).

Skull of Muraenosaurus leedsi, based upon the specimens LEICT G18.1996 and BMNH R.2861. Scale bar = 100 mm. Illustration from Evans (1999), page 195.

Reconstructions of the cranium and mandible of the plesiosaur Muraenosaurus leedsi. Image from Noè et al. (2017), page 142.

During the middle of the Jurassic Period 165 MYA, southern England was covered by the Tethys Sea, a warm shallow sea which inundated much of Europe during the Jurassic and Cretaceous, and the climate would have been similar to the modern-day Caribbean. Muraenosaurus shared its mid-Jurassic marine habitat with many other species of aquatic reptiles including the plesiosaurs Cryptoclidus and Picrocleidus, the pliosaurs Liopleurodon, Peloneustes, and Simolestes, the ichthyosaur Ophthalmosaurus, and the marine crocodylomorphs Suchodus, Thalattosuchus, Gracilineustes, and Tyrannoneustes.

Muraenosaurus leedsi. © Jason R. Abdale (July 15, 2025).

Although known from numerous specimens found in western Europe, there’s also a possibility that Muraenosaurus could have inhabited other places around the world during the middle Jurassic. Plesiosaur vertebrae identified as Elasmosauridae (collection ID code: LACM 56073) were found by George P. Kanakoff within the Bedford Canyon Formation in Orange County, California (Hilton 2003, pages 101, 233, 272). According to an e-mail which I received on July 24, 2025 from Maureen Walsh, Collections Manager at the Dinosaur Institute of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, the fossils were collected on December 24, 1974 within the Santa Ana Mountains near Modjeska Peak. The original note accompanying the fossils states that they might be from the Bedford Canyon Formation, but this wasn’t definitely proven. The Bedford Canyon Formation dates from the middle of the Bajocian Stage to the early Callovian Stage of the middle Jurassic Period (Imlay 1980, page 61) approximately 169-165 MYA. These curious vertebrae might be a specimen of Muraenosaurus, since they date to the same time that Muraenosaurus was alive and because Muraenosaurus was formerly classified as an elasmosaurid before being reclassified as a cryptoclidid in the early 2000s. However, somebody more knowledgeable in plesiosaur anatomy than myself will have to do a comparative analysis between these bones from California and bones found in England and France to see if they match up. The age of the specimens will also need to be checked to see if they do indeed come from the Bedford Canyon Formation or if they date to another time.

Plesiosaur vertebrae found in 1974 near Modjeska Peak, Orange County, California (collection ID code: LACM 56073). Photographs courtesy of the Dinosaur Institute, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (July 24, 2025). Images used with permission.

I truly enjoy writing my articles and drawing my art, but it’s increasingly clear that I can’t keep this up without your gracious financial assistance. Kindly check out my pages on Redbubble and Fine Art America if you want to purchase merch of my artwork. Consider buying my ancient Roman history books Four Days in September: The Battle of Teutoburg and The Great Illyrian Revolt if you or someone that you know loves that topic, or my ancient Egyptian novel Servant of a Living God if you enjoy action and adventure.

Please consider becoming a patron on my Patreon page so that I can afford to purchase the art supplies and research materials that I need to keep posting art and articles onto this website. Professional art supplies are pricey, and many research articles are “pay to read”, and some academic journals are rather expensive. Patreon donations are just $1 per month – that’s it. If everyone gave just $1 per month, it would go a long way to purchase the stuff that I need to keep my blog “Dinosaurs and Barbarians” running.

Take care, and, as always, keep your pencils sharp.

Bibliography

Books

Andrews, Charles William. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Marine Reptiles of the Oxford Clay. Based on the Leeds Collection in the British Museum (Natural History), London, Part 1. London: The British Museum, 1910.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/125533#page/7/mode/1up.

Hilton, Richard P. Dinosaurs and Other Mesozoic Reptiles of California. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Articles

Brown, D. S. (1981). “The English Upper Jurassic Plesiosauroidea (Reptilia) and a review of the phylogeny and classification of the Plesiosauria”. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Geology, volume 35, issue 4 (December 17, 1981). Pages 253-347.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/33428283#page/277/mode/1up.

Evans, Mark (1999). “A new reconstruction of the skull of the Callovian elasmosaurid plesiosaur Muraenosaurus leedsii Seeley”. Mercian Geologist, volume 14, issue 4 (1999). Pages 191-196.

https://www.emgs.org.uk/uploads/1/4/9/1/149143154/mg14_4_1999_complete.pdf#page=41.

Imlay, Ralph W. (1980). “Jurassic paleobiogeography of the conterminous United States in its continental setting”. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper, number 1062. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1980. Pages 1-134.

https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/1062/report.pdf.

Noè, Leslie F.; Taylor, Michael A.; Gómez-Pérez, Marcela (2017). “An integrated approach to understanding the role of the long neck in plesiosaurs”. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, volume 62, issue 1 (2017). Pages 137-162.

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/cf8e/cba90a7a60d4483c1c51625d8a736be9449e.pdf.

O’Keefe, Frank Robin (2001). “A cladistics analysis and taxonomic revision of the Plesiosauria (Reptilia: Sauropterygia)”. Acta Zoologica Fennica, volume 213 (December 11, 2001). Pages 1-63.

https://mds.marshall.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1051&context=bio_sciences_faculty.

Seeley, Harry G. (1874). “On Muraenosaurus Leedsii, a Plesiosaurian from the Oxford Clay. Part I”. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, volume 30 (1874) Pages 197-208.

https://ia600805.us.archive.org/view_archive.php?archive=/13/items/crossref-pre-1909-scholarly-works/10.1144%252Fgsl.jgs.1873.029.01-02.46.zip&file=10.1144%252Fgsl.jgs.1874.030.01-04.35.pdf.

Seeley, Harry G. (1892). “The nature of the shoulder girdle and clavicular arch in Sauropterygia”. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, volume 51 (308-314). Pages 119-151.

Websites

British Geological Survey. “Oxford Clay Formation”.

https://webapps.bgs.ac.uk/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?pub=OXC. Accessed on July 8, 2025.

Paleofile. “Muraenosaurus”.

http://www.paleofile.com/Sauropterygia/Muraenosaurus.asp. Accessed on July 9, 2025.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment