There are many iconic predators of the Seven Seas: the Great White Shark, the Killer Whale, the Giant Squid, and others. In prehistoric times, the list of “epic marine killers” was much longer. One of those who definitely deserves a place on this list is Xiphactinus, a massive 18 foot long carnivorous fish which swam the world’s oceans during the middle and late Cretaceous Period 100-66 million years ago.

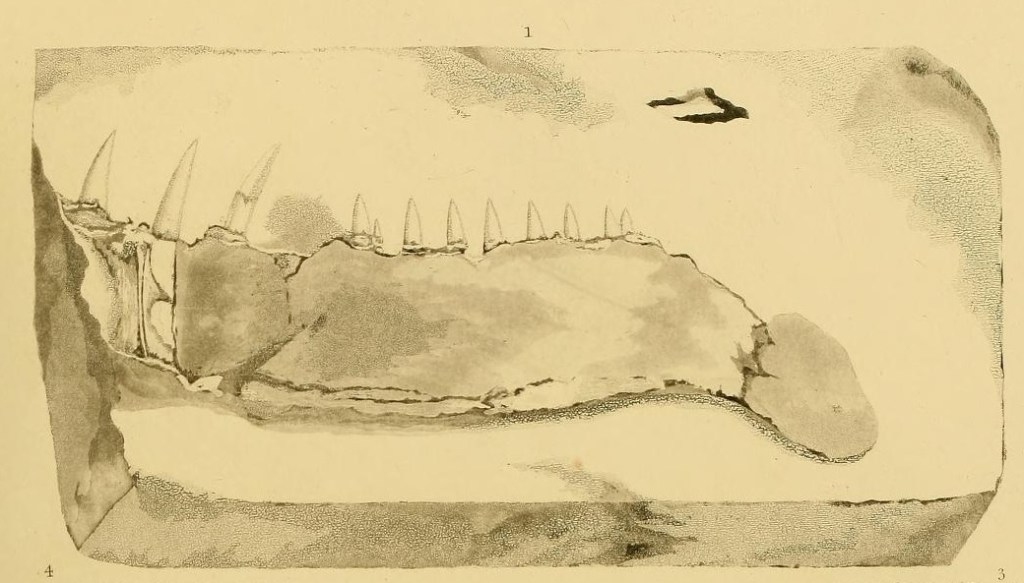

Fossils of this fish were first discovered during the 1700s in the vicinity of Mount Saint-Pierre near Maastricht, Netherlands. The rock layers here date to the end of the Cretaceous Period 72-66 million years ago (Willems and Rodet 2018, page 177). In 1799, the French geologist Barthélemy Faujas-de-St.-Fond (1741-1819) was the first person to both write about and illustrate these fossils, consisting of a fragmentary jaw and some very formidable looking teeth. The fossil was quickly described as Dents et portion de machoire d’un poisson inconnu (“Teeth and portion of jaw of an unknown fish”) and Un morceau de pierre figuré de grandeur naturelle avec un reste de mâchoire osseuse et des dents luisantes et comme cornées, de couleur gris foncé, d’un animal inconnu (“A life-sized figure of a piece of stone with the remnant of a jawbone and shiny horn-shaped dark grey teeth of an unknown animal”) (Faujas-de-St.-Fond 1799, Pages 112-113). He concluded these remarks by stating that this partial jaw and all of the other fossils found with it were in the collection of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, France (Faujas-de-St.-Fond 1799, Page 113).

This is the oldest-known illustration of a Xiphactinus fossil – a fragmentary jaw discovered in the chalk at Mount Saint-Pierre near Maastricht, Netherlands. Faujas-de-St.-Fond, Barthélemy. Histoire Naturelle de la Montagne de Saint-Pierre de Maestricht. Paris: H. J. Jansen, 1799. Table XIX.

https://archive.org/details/histoirenaturel00fauj/page/112/mode/2up.

During the early 1820s, another partial specimen was uncovered within southern England in a region called the South Downs, which is a vast area of countryside within the English counties of Hampshire and Sussex extending for 260 square miles in area. This region is renowned for its astounding ancient Roman archaeological sites, such as the spectacular Roman villas located at Bignor and Fishbourne. However, it is also a rich site for marine fossils dating to the Cretaceous Period. In 1822, Dr. Gideon Mantell, a medical doctor and avid rockhound (who would later earn scientific immortality as the man who named Iguanodon) wrote a book entitled The Fossils of the South Downs. In its pages is an illustration of a fish’s lower jaw measuring 5 and a half inches long featuring some truly vicious-looking teeth which was found in the Lower Chalk near the Sussex town of Lewes (Mantell 1822, page 241). Of this find, Dr. Mantell says the following:

“The lower jaw; vertebra, &c. of an unknown fish?…The fossils delineated in this plate were imbedded in the same block of chalk, and most probably belonged to the same individual. They consist of part of the lower jaw, several tusks or defences, a vertebra, and a cylindrical bone. The jaw, fig. 1, of which the right side only remains, is attached to the chalk, by its inner surface, the exterior being exposed. It is 5.5 inches long; 1.2 inch wide; and 0.5 inch thick in front: it contains twelve smooth pointed teeth. These are slightly convex, very brittle, and possess a glossy surface. The three anterior ones are gently curved; their fangs are hollow, and placed in sockets that extend almost to the base of the jaw. The nine posterior teeth are of a lanceolate form, and probably destitute of fangs, appearing as if attached to the jaw by anchylosis. The two anterior and posterior teeth of this set, are placed close to each other; one of them is very small and delicate. A fragment of bone is imbedded immediately above the posterior part of the jaw; and although it is too imperfect to admit of any satisfactory conjecture of its nature, yet there seems reason to suppose, that it may be the remains of a palate bone. The specimens figs. 3, and 4, are corresponding portions, and were by accident broken from the front of the jaw; but the edges of the respective pieces were so much mutilated, that I have been unable to ascertain the precise situation they originally occupied. They consist of a portion of the jaw, with the remains of five tusks or defences, only one of which is entire; these resemble the teeth in the fossil figured by Faujas St. Fond, Hist. Nat. de la Montagne de St. Pierre, Tab. xix. fig. 10; which that distinguished naturalist describes as ‘Portion de machoire d’un poisson imconnu’. The vertebra (fig. 2.) is deeply concave on both sides, and the inner surface is marked with numerous annular ridges; a small portion of the spinous process still remains. The bone (fig. 5.) is cylindrical in the centre, but the two extremities are nearly flat, and extend in opposite directions. These parts have suffered so much from compression, that it is scarcely possible to ascertain their original shape. It seems probable that they were once convex, and formed articulating surfaces; if this opinion be correct, the bone may, perhaps, have been a humerus. Of the nature of the original animal, I must confess myself incapable of offering any satisfactory conjectures: the fangs of the anterior teeth, like those of the crocodile, are hollow, fixed in sockets, and not attached to the jaw; but their smooth polished surface, and flattened form, separate them most decidedly from the animals of that tribe. The posterior teeth are affixed to the edge of the jaw, a mode of dentature observable in many kinds of fishes. The structure of the vertebra is decidedly that of a fish, the conical cavities being very deep; and it possesses the annular markings so constantly observable in the vertebrae of fishes. The cylindrical bone is too much injured to allow of any correct inference being drawn from it. From these circumstances it seems probable, that the remains before us are those of an osseous fish, of a species, and perhaps genus, distinct from any previously known” (Mantell 1822, pages 241-242).

The lower jaw found near the town of Lewes in Sussex, England. Mantell, Gideon. The Fossils of the South Downs, or, Illustrations of the Geology of Sussex. London: Lupton Relfe, 1822. Table XLII.

https://archive.org/details/fossilsofsouthdo00mant/page/n425/mode/1up.

Afterwards, Gideon Mantell seemed to have second thoughts about his original identification of this jaw belonging to a large fish and supposed that it might actually belong to some prehistoric reptile. In 1830, the eminent Swiss ichthyologist Louis Agassiz christened it Megalodon sauroides, “lizard-like big tooth” (Hartmann 1830, page 51). Three years later, Agassiz recognized the fossil jaw from Lewes as indeed belonging to a fish, as Mantell had initially supposed. Furthermore, Agassiz pointed out that the genus name Megalodon had already been coined by James Sowerby for a genus of prehistoric mollusk, and therefore couldn’t be used again. Consequently, Agassiz renamed the fish jawbone from Lewes to Hypsodon lewesiensis. The genus name Hypsodon means “height tooth” in ancient Greek (ὕψος / hypsos, “height/summit/peak”; ὀδών / odon, “tooth”) due to the teeth’s great size (Roberts 1839, page 81). The fossil is held in the British Museum of Natural History (collection ID code: BMNH 4066) (PaleoBio Database. “Cladocyclus lewesiensis”). He cursorily described is as Très-grande espèce à dents formidables, “Very large species with formidable teeth”. Additionally, he named two other species, H. toliapicus and H. oblongus which were De l’argile de Londres de Sheppy, “From the London Clay of Sheppy” (Agassiz 1833, page 8), and then later on gave a more thorough description of the finds, and hypothesized that the creature belonged to the family Sphyraenoides (mis-spelling of Sphyraenidae; barracudas and their relatives) due to the teeth being similar in shape to those of a modern-day barracuda (Agassiz 1833, pages 99-101).

As stated above, two of the three specimens were found within the London Clay at the Isle of Sheppey, which is a sizeable island located immediately south of the mouth of the Thames River. However, the London Clay is dated to the early part of the Eocene Epoch of the Paleogene Period, while the area near Lewes has fossils which date to the late Cretaceous Period. The species Hypsodon toliapicus and Hypsodon oblongus were later renamed to Megalops, which had been named in 1803 (Woodward 1901, pages 24, 26).

In 1848, Gideon Mantell classified the teeth of Hypsodon as “sauroid” or “lizard-like” due to their similarity to reptile teeth (Mantell 1848, page 343). This similarity was especially noted when comparing the teeth of Hypsodon to those of the Cretaceous pliosaur Polyptychodon, but the famous British paleontologist Sir Richard Owen noticed some key differences in the teeth’s internal and external structure (Owen 1842, pages 156-157). However, aside from some teeth and a few fragmentary lower jaws, not much was known about this animal. However, that would change with some spectacular discoveries made across the Atlantic within the American West.

Within Cretaceous-aged deposits in Kansas, Dr. George Sternberg found a large spine from a pectoral fin measuring 16 inches long (collection ID code: USNM V52). In 1870, Dr. Joseph Leidy gave it the name Xiphactinus audax, “the audacious sword-ray”. He suspected that it belonged to “some huge siluroid fish” (Leidy 1870, page 12). The family Siluridae is a group of catfish native to Europe and Asia, the largest of them being the Wels Catfish (Silurus glanis). However, all members of Siluridae inhabit freshwater, and the fin ray found by George Sternberg was found within marine deposits. Professor Edward D. Cope stated that the name Xiphactinus was a junior synonym of Saurocephalus, and Ferdinand V. Hayden agreed with him (Cope 1870, page 530; Hayden 1871, page 418). To be fair, the two animals were related, as both belong to the broader order Ichthyodectiformes, but belong to different families.

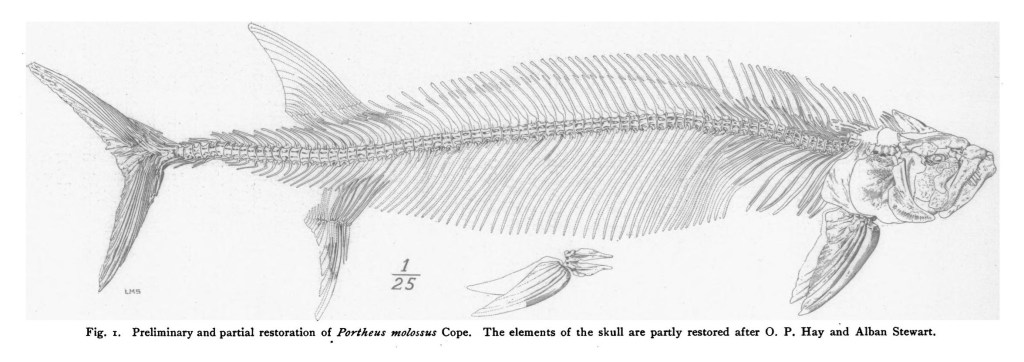

In 1871, at Fox Creek Canyon in Kansas, Martin V. Hartwell, who served as one of the guides to Prof. Edward D. Cope, discovered “almost the entire skeleton of a large fish, furnished with an uncommonly powerful offensive dentition”. In 1871, Edward D. Cope gave it the name Portheus molossus. Cope also commented that he and his men found several individuals of this animal, leading him to suspect that it was quite abundant within its environment, and that “it was probably the dread of its contemporaries among the fishes as well as the smaller saurians” (Cope 1871, pages 174-175). Multiple species were ascribed to this genus based upon slight variations in their anatomy, including P. molossus (type species), P. arctuatus, P. gladius, P. lestrio, P. mudgei, and P. thaumas. All of these species were found within the Niobrara Formation of Kansas (Hayden 1875, pages 273-274), which dates from 87-82 MYA, and this naturally leads one to suspect if these different species might all be the same taxon.

Skeletal reconstruction of Xiphactinus audax (formerly known as Portheus molossus). Osborn, Henry Fairfield (1904). “The Great Cretaceous Fish Portheus molossus Cope”. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, volume 20 (1904). Page 378.

https://archive.org/details/bulletin-american-museum-natural-history-20-377-381/page/2/mode/2up?view=theater.

In 1875, Edward D. Cope alleged that some of the specimens which had previously been referred to as Hypsodon were actually Portheus based upon the size and shape of the teeth. Cope differentiated the two by saying that Hypsodon had teeth in its lower jaw which were all of equal height, while Portheus had lower teeth which were of varying sizes (Cope 1875, pages 23, 189-190). In 1877, Edwin T. Newton stated Hypsodon and Portheus were different genera due to differences in the shape of their skulls (Newton 1877, pages 508-509). Newton then went on to create several new species of Portheus (P. daviesii, P. gaultinus, and P. mantelli) based upon very minor differences in anatomy (Newton 1877, pages 510-520).

There were some shake-ups to Hypsodon’s status in the late 1880s and into the 1890s. In 1887, it was stated that the fossil jaw which had been found in Lewes in the early 1800s and had been designated as the holotype specimen of Hypsodon lewesiensis actually belonged to the genus Cladocyclus (hitherto known only from Brazil) and it was redesignated Cladocyclus lewesiensis (PaleoBio Database. “Cladocyclus lewesiensis”). In 1889, Arthur S. Woodward said that the specimen named Hypsodon by Agassiz was later found to be a chimera of two different genera, one of which was determined to belong to Pachyrhizodus, and the other being Portheus. Therefore, the name Hypsodon was invalid (Woodward 1889, pages 310-311). In 1890, Arthur S. Woodward and Charles Sherborn stated that Hypsodon lewesiensis was a synonym of Portheus mantelli, and further stated that the genus Portheus was only divided into four species: P. daviesi, P. gaultinus, P. mantelli, and an indeterminate fourth species (Woodward and Sherborn 1890, page 160).

Then in 1898 came another bombshell. Oliver P. Hay stated that he compared the fossils remains ascribed to Portheus to those ascribed to Xiphactinus, had he found no discernable differences between them, and therefore the two genera were actually the same. Since Xiphactinus was named first, that name ought to have priority, and therefore all of the species formerly ascribed to Portheus were now redesignated as species of Xiphactinus (Hay 1898a, page 27; Hay 1898b, pages 229-230). That same year, Alban Stewart said that the multitude of species which were ascribed to Xiphactinus and its various synonyms were not entirely different species but were actually slight anatomical differences amongst individuals. He concluded his article with the following statement: “I would seem that X. molossus and X. thaumas are synonymous, and as Cope has admitted that X. thaumas and X. audax are synonyms, this form should be known in the future as Xiphactinus audax” (Stewart 1898, pages 115-119). Thus, all specimens of Hypsodon, Portheus, and Xiphactinus were lumped into the species Xiphactinus audax.

In 1901, Arthur S. Woodward stated that he did not consider the name Hypsodon a valid name for any fish since the name didn’t apply to any species in particular. In 1915, Theodore Cockerell suggested that Hypsodon was the senior synonym of Pachyrhizodus, which had been named by Frederick Dixon in 1850. This was re-iterated in 1965 by David Bardack who stated that the genus Hypsodon was actually a pachyrhizodid, not an ichthyodectid as Agassiz had stated: “By priority Hypsodon should apply to a pachyrhizodid, for the first specimen mentioned by Agassiz when he described the single species of Hypsodon is the pachyrhizodid that Woodward (1901) named Thrissopater magnus” (Bardack 1965, page 37). Due to all of these confusions, specimens which have previously been lumped under Hypsodon have since been reclassified into several new species, including Xiphactinus audax, Xiphactinus mantelli, Ichthyodectes minor, Gillicus arcuatus, and Cladocyclus lewesiensis, and the name Hypsodon fell out of usage (Cockerell 1919, pages 177-179; Bardack 1965, pages 11, 37, 52, 61-62).

In 1917, Theodore Cockerell said of Hypsodon, “that generic name appears to belong properly to the fishes usually called Portheus” (Cockerell 1917, page 62). He also stated that the European specimens which were ascribed to the genus Cladocyclus (including C. lewesiensis) were different from those of South America, and therefore they ought to be given a different genus name, but Cockerell shied away from doing so himself (Cockerell 1917, page 62).

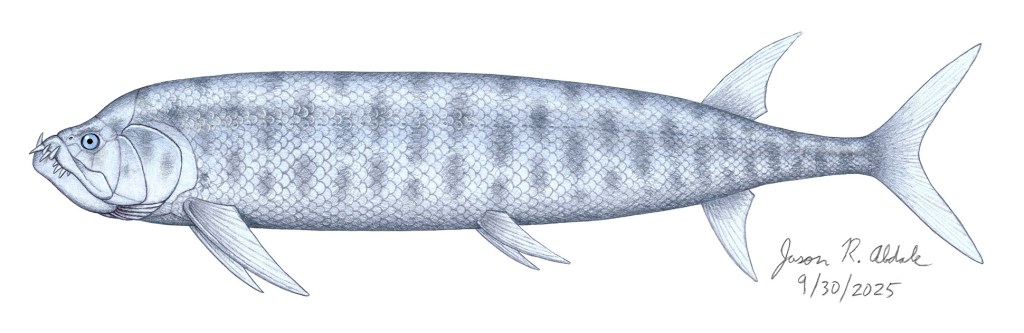

Xiphactinus belonged to an order of prehistoric fish called Ichthyodectiformes, which included genera like Ichthyodectes, Occithrissops, Cladocyclus, and Gillicus. It was also by far the largest member of that group. Oliver P. Hay remarked how similar Xiphactinus was in overall appearance to a modern-day tarpon, and he spent a considerable amount of time thoroughly comparing the two (Hay 1898a, pages 27-54). However tarpons don’t measure 18 feet long and have a mouth packed with huge teeth. No wonder that Mike Everhart nicknamed it “the bulldog fish” (“Xiphactinus audax Leidy 1870 (…not Portheus molossus Cope 1872): Largest Bony Fish of the Late Cretaceous Seas”). Edward D. Cope surmised that this mighty fish had a monstrous appetite to match its equally monstrous size and appearance, and fossil evidence showed that he was right. One fossil specimen known as “the fish within a fish” is of a 14 foot long Xiphactinus which swallowed (and choked to death on) a 6 foot long Gillicus. In fact, we have found several instances of Xiphactinus biting off far more than it could chew, and possibly rupturing its stomach open in the process.

The geologically oldest specimen of Xiphactinus which I’ve been able to find was discovered in the early 1900s within the Mowry Shale of Wyoming, dated to the Cenomanian Stage of the middle Cretaceous about 100 MYA. This was tentatively classified by Theodore Cockerell as Hypsodon(?) granulosus, though Cockerell also confusingly stated the name was synonymous with Xiphactinus audax (Cockerell 1919, pages 171, 177-179). Another Cenomanian-aged specimen was found within the La Aguada Member of the La Luna Formation in western Venezuela (Carrillo-Briceño et al. 2012, pages 327-335). The youngest specimens of Xiphactinus audax are found at Maastricht, Netherlands – the first specimen of the animal to be found, as mentioned at the start of this article – and also from Patagonia, Argentina within rocks dating to the very end of the Cretaceous Period 66 MYA (De Pasqua et al. 2020, pages 327-331). It seems that the species Xiphactinus audax was exceptionally long-lived. While the vast multitude of Xiphactinus fossils have been found within the center of the United States, particularly in Kansas, fossils of this great fish have also been found in Canada (Vavrek et al. 2016, pages 89-100), America’s Gulf Coast and eastern seaboard (Schwimmer et al. 1997, pages 610-615), Venezuela, Argentina, England, the Netherlands, and in Queensland, Australia (Woodward 1894, pages 444-447). It seems clear that Xiphactinus had a worldwide distribution during its life, and the geographic range of fossils found and the wide range of dates, not to mention the sheer abundance of fossils that have been found, are testament to how successful Xiphactinus was.

Xiphactinus audax. © Jason R. Abdale (September 30, 2025).

I truly enjoy writing my articles and drawing my art, but it’s increasingly clear that I can’t keep this up without your gracious financial assistance. Kindly check out my pages on Redbubble and Fine Art America if you want to purchase merch of my artwork. Consider buying my ancient Roman history books Four Days in September: The Battle of Teutoburg and The Great Illyrian Revolt if you or someone that you know loves that topic, or my ancient Egyptian novel Servant of a Living God if you enjoy action and adventure.

Please consider becoming a patron on my Patreon page so that I can afford to purchase the art supplies and research materials that I need to keep posting art and articles onto this website. Professional art supplies are pricey, and many research articles are “pay to read”, and some academic journals are rather expensive. Patreon donations are just $1 per month – that’s it. If everyone gave just $1 per month, it would go a long way to purchase the stuff that I need to keep my blog “Dinosaurs and Barbarians” running.

Keep your pencils sharp.

Bibliography

Books

Agassiz, Louis. Recherches des Poissones Fossiles, Volume V. Neuchatel: Imprimerie de Petit Pierre, 1833-1845.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Recherches_sur_les_poissons_fossiles/_yc_AAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Cope, Edward D. The Vertebrata of the Cretaceous Formations of the West. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1875.

https://darwin-online.org.uk/converted/pdf/1875_Cope_vertebrata_A3851.pdf.

Faujas-de-St.-Fond, Barthélemy. Histoire Naturelle de la Montagne de Saint-Pierre de Maestricht. Paris: H. J. Jansen, 1799.

https://archive.org/details/histoirenaturel00fauj/page/n7/mode/2up.

Hartmann, Friedrich. Systematische Uebersicht der Versteinerungen Würtembergs. Tübingen: Heinrich Lanpp, 1830.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Systematische_Uebersicht_der_Versteineru/XQAtvJ9RTB8C?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Hayden, F. V. Preliminary Report of the United States Geological Survey of Wyoming, and Portions of Contiguous Territories. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1871.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Preliminary_Report_of_the_United_States/FAm_Ml1aW98C?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Hayden, F. V. Report of the United States Geological Survey of the Territories, Volume II. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1875.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Report_of_the_United_States_Geological_S/Vviojjc4UrkC?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Mantell, Gideon. The Fossils of the South Downs, or, Illustrations of the Geology of Sussex. London: Lupton Relfe, 1822.

https://archive.org/details/fossilsofsouthdo00mant/page/n9/mode/2up.

Mantell, Gideon Algernon. The Wonders of Geology, Volume I, Sixth Edition. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1848.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Wonders_of_Geology/lmmunXBFL9EC?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Roberts, George. An Etymological and Explanatory Dictionary of the Terms and Language of Geology. London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1839.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/An_etymological_and_explanatory_dictiona/PXcEAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Woodward, Arthur Smith; Sherborn, Charles Davies. A Catalogue of British Fossil Vertebrata. London: Dulau & Co., 1890.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_Catalogue_of_British_Fossil_Vertebrata/F2ksAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Woodward, Arthur Smith. Catalogue of the Fossil Fishes in the British Museum (Natural History), Part IV. London: Longmans & Co., 1901.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Catalogue_of_the_Fossil_Fishes_in_the_Br/ZtEKAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Articles

Bardack, David (1965). “Anatomy and evolution of Chirocentrid fishes”. University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions – Vertebrata, article 10. Pages 1-88.

https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/handle/1808/3814.

Carrillo-Briceño, Jorge; Alvarado-Ortega, Jesús; Torres, Carlos (2012). “Primer registro de Xiphactinus Leidy, 1870, (Teleostei: Ichthyodectiformes) en el Cretácico Superior de América del Sur (Formación La Luna, Venezuela)”. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia, volume 15, issue 3 (September-December 2012). Pages 327-335.

https://www.sbpbrasil.org/revista/edicoes/15_3/08_CarrilloBriceno_et_al.pdf.

Cockerell, T. D. A. (1917). “European Fossil Fish Scales”. The American Naturalist, volume 51, issue 601 (1917). Pages 61-63.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/279587.

Cockerell, T. D. A. (1919). “Some American Cretaceous Fish Scales, with Notes on the Classification and Distribution of Cretaceous Fishes”. U.S. Geological Survey. Shorter Contributions to General Geology, professional paper 120. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1919. Pages 165-203.

https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/0120i/report.pdf.

Cope, Edward D. (1870). “On the Saurodontidae”. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, volume 11 (November 18, 1870). Pages 529-538.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/981509.pdf.

Cope, Edward D. (1871). “Stated Meeting – October 20, 1871”. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, volume 12 (1871). Pages 173-176.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/108737#page/187/mode/1up.

De Pasqua, Julieta J.; Agnolin, Federico L.; Bogan, Sergio (2020). “First record of the ichthyodectiform fish Xiphactinus (Teleostei) from Patagonia, Argentina”. Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology, volume 44, issue 2 (March 2020). Pages 327-331.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/figure/10.1080/03115518.2019.1702221?scroll=top&needAccess=true.

Hay, O. P. (1898a). “Observations on the genus of fossil fishes called by Professor Cope, Portheus, by Dr. Leidy, Xiphactinus”. Zoological Bulletin, volume 2, issue 1 (July 1898). Pages 25-54.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Zo%C3%B6logical_Bulletin/f-jzAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=hypsodon+portheus&pg=PA25&printsec=frontcover.

Hay, O. P. (1898b). “Notes on species of Ichthyodectes, including the new species I. cruentus, and on the related and herein established genus Gillicus”. The American Journal of Science, volume 6, issue 33 (September 1898). Pages 225-232.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_American_Journal_of_Science/bQ3SAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Portheus+Xiphactinus&pg=PA230&printsec=frontcover.

Leidy, Joseph (1870). “Remarks on Ichthyodorulites and on certain fossil Mammalia”. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, volume 22 (March 1870). Pages 12-13.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/84763#page/22/mode/1up.

Newton, E. T. (1877). “On the remains of Hypsodon, Portheus and Ichthyodectes from British Cretaceous strata, with descriptions of a new species”. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, volume 33 (1877). Pages 505-529, Pl. XXII.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Quarterly_Journal_of_the_Geological/stwGAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Cope+Portheus&pg=RA1-PA509&printsec=frontcover.

Osborn, Henry Fairfield (1904). “The Great Cretaceous Fish Portheus molossus Cope”. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, volume 20 (1904). Pages 377-381.

https://archive.org/details/bulletin-american-museum-natural-history-20-377-381/page/2/mode/2up?view=theater.

Owen, Richard (1841). “On British Fossil Reptiles, Part II”. Report of the Eleventh Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, held at Plymouth in July 1841. London: John Murray, 1842.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Report_of_the_Annual_Meeting/3XVRAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Schwimmer, David R.; Stewart, J. D.; Williams, G. Dent (1997). “Xiphactinus vetus and the Distribution of Xiphactinus Species in the Eastern United States”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 17, issue 3 (September 1997). Pages 610-615.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254314020_Xiphactinus_vetus_and_the_distribution_of_Xiphactinus_species_in_the_eastern_United_States.

Stewart, Alban (1898). “Individual Variations in the genus Xiphactinus Leidy”. Kansas University Quarterly, volume 7, issue 3 (July 1898). Pages 115-119.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Collected_papers/Z3pGAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Vavrek, Matthew J.; Murray, Alison M.; Bell, Phil R. (2016). “Xiphactinus audax Leidy, 1870 from the Puskwaskau Formation (Santonian to Campanian) of northwestern Alberta, Canada and the distribution of Xiphactinus in North America”. Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Palaeontology, volume 1, issue 1 (February 4, 2016). Pages 89-100.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292983703_Xiphactinus_audax_Leidy_1870_from_the_Puskwaskau_Formation_Santonian_to_Campanian_of_northwestern_Alberta_Canada_and_the_distribution_of_Xiphactinus_in_North_America.

Willems, Luc; Rodet, Joël (2018). “Karst and Underground Landscapes in the Cretaceous Chalk and Calcarenite of the Belgian-Dutch Border—The Montagne Saint-Pierre”. In Demoulin, Alain, ed. Landscapes and Landforms of Belgium and Luxembourg. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018. Pages 177-192.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Landscapes_and_Landforms_of_Belgium_and/qrsyDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Woodward, Arthur Smith (1894). “On some fish remains of the genera Portheus and Cladocyclus from the Rolling Downs Formation (lower Cretaceous) of Queensland”. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, volume 14, issue 84 (1894). Pages 444-447.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/24343450#page/476/mode/1up.

Woodward, Arthur Smith (1889). “A Synopsis of the Vertebrate Fossils of the English Chalk”. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, volume 10 – 1887-1888 (1889). Pages 273-338.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Proceedings_of_the_Geologists_Associatio/GVnzAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=hypsodon+portheus&pg=RA1-PA311&printsec=frontcover.

Websites

Oceans of Kansas. “Xiphactinus audax Leidy 1870 (…not Portheus molossus Cope 1872): Largest Bony Fish of the Late Cretaceous Seas”, by Mike Everhart (August 1, 2013).

https://oceansofkansas.com/xiphac.html. Accessed on October 3, 2025.

PaleoBio Database. “Cladocyclus lewesiensis”.

https://paleobiodb.org/classic/checkTaxonInfo?taxon_no=263479&is_real_user=1#:~:text=Cladocyclus%20lewesiensis%20was%20named%20by%20Agassiz%20(1887).,and%20it%20is%20a%203D%20body%20fossil. Accessed on October 3, 2025.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment