Introduction

When one hears the word “dinosaur”, one often imagines the sauropods – the large long-necked long-tailed plant-eaters which came to dominate Earth’s landmasses during the Jurassic Period. The sauropods died out in North America at the end of the Jurassic Period 145 million years ago, and it’s still not clear how or why. However, they continued to survive in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, and especially South America. Some of these South American sauropods reached absolutely enormous sizes during the Cretaceous Period, becoming the largest animals that ever walked on this planet, fully justifying their name “titanosaurs”.

But the titanosaurs didn’t just live in South America. Species belonging to this group have also been found within rocks dating to the middle and late Cretaceous Period in places like France, Romania, Egypt, India, Mongolia, China, Australia, and even the United States. The only titanosaurian sauropod which is conclusively known to have inhabited North America was Alamosaurus, a massive sauropod dinosaur which lived at the end of the Cretaceous Period 70-66 million years ago. Fossils of this giant herbivore have so far been found in the American states of Utah, New Mexico, and Texas, and it’s likely that Alamosaurus roamed throughout the rest of western North America from Alberta to Mexico.

However, despite being known to science for over a hundred years, Alamosaurus remains an enigmatic creature. There is still much that is unknown about it largely due to the fact that it is known from individual bones or handfuls of bones found in a wide range of localities. Putting together an image of what Alamosaurus looked like is like trying to complete a jigsaw puzzle using individual pieces which are scattered across the length and breadth of three different states – a few arm bones here, a leg bone or two there, a handful of vertebrae over here, so forth and so forth. In fact, we’re not 100% sure that all of these bones even belong to the same species. This article will try to tell you as much as we know about Alamosaurus and also what there’s still left to learn.

History of discoveries

In 1916, John B. Reeside Jr. of the United States Geological Survey was prospecting for fossils in northwestern New Mexico within the Ojo Alamo Formation. This geologic formation transcends the Mesozoic/Cenozoic boundary, with the lower rock layers called the Naashoibito Member dating to the Maastrichtian Stage, the very last stage of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 70-66 million years ago, and the upper layers called the Kimbeto Member dating to the Danian Stage of the Paleocene Epoch, the first stage of the Paleogene Period, 65-61 million years ago (Sullivan et al. 2005, pages 395-407). According to Thomas Lehman, the Naashoibito Member’s strata are divided into four units which were deposited by low-sinuosity meandering and braided streams within a floodplain (Lehman 1985, pages 55, 68-71). At a place called Barrel Springs Arroyo one mile south of Ojo Alamo, San Juan County, New Mexico, Reeside discovered a centrum (the drum-like disc which forms the bulk of the vertebra’s body) from a dinosaur’s tail vertebra and a caudal vertebra’s neural spine within a bed of shale three to eight feet above the base of the Ojo Alamo Formation. The bones were sent to Washington, D.C. to the United States National Museum, more commonly known as the Smithsonian Institution, for further study (collection ID code: USNM 15658) (Gilmore 1946, page 30).

In June 1921, John B. Reeside Jr. returned to the same area and discovered a left scapula and right ischium found at a distance of 200 feet from each other. Their size was enormous: the nearly-complete scapula measured 5 feet tall (and would have measured slightly longer if fully complete) and the ischium measured 31.88 inches (81 cm). Their shape clearly identified them as belonging to a sauropod dinosaur. However, following the Jurassic/Cretaceous transition, sauropods went into decline in North America, and it was believed that they had been completely extirpated from the continent during the middle Cretaceous. Yet these two bones were obviously within the uppermost strata of the Cretaceous, a time when sauropod dinosaurs were utterly unknown to inhabit North America. Like the fossils found in 1916, these fossils were also sent to the Smithsonian Institution (Gilmore 1921, page 274; Gilmore 1922, pages 1-2).

In September 1921, the discovery of bones from New Mexico was reported in the scientific literature by Charles W. Gilmore, the head vertebrate paleontologist of the Smithsonian Institution (Gilmore 1921, page 274). The following year, he wrote a more comprehensive description of the finds, and he also gave them a name – Alamosaurus sanjuanensis, “Ojo Alamo Lizard from the San Juan Basin”. Contrary to what some people might believe, Alamosaurus was not named after the famous Alamo in San Antonio, Texas. Instead, it’s named after the Ojo Alamo Formation in northwestern New Mexico. The holotype is housed within the Smithsonian Institution (collection ID codes: USNM 10486 and USNM 10487) (Gilmore 1922, pages 1-9). Gilmore noted that the dating of these sauropod bones to the late Cretaceous was met with skepticism at the time (Gilmore 1938, pages 299-300).

In 1922, Charles Sternberg visited Barrel Springs Arroyo and collected a fragment of the right ilium and three partial sacral vertebrae of a large sauropod. These fossils made their way into the collections of the University of Uppsala in Sweden, where they were forgotten about until the 1970s. Because these fossils were collected from the same locality as the holotype specimen of Alamosaurus, and therefore might belong to the same individual, they were designated as “topotypes” of Alamosaurus (Mateer 1976, pages 93-95).

In 1924, a paleontological expedition from Amherst College led by Prof. Frederic B. Loomis went into the San Juan Basin and found the remains of numerous dinosaurs, including a partial left humerus from an Alamosaurus which was found within the Naashoibito Member of the Ojo Alamo Formation. This bone was eventually put on display in the Springfield Science Museum in Springfield, Massachusetts (collection ID code: SSM 5428) (Dalman and Lucas 2016, pages 61-66).

In June 1937, the Smithsonian Institution sent a paleontological expedition into the Wasatch Plateau of central Utah. On June 15, George B. Pearce discovered another specimen of Alamosaurus (collection ID code: USNM 15660) on the southwestern face of North Horn Mountain in Manti National Forest, Emery County. The bones were found within the lower strata of the North Horn Formation (Gilmore 1946, pages 29-30). The North Horn Formation consists largely of shale interbedded with layers of sandstone and limestone. According to Edmund Spieker, “Units 1 and 3 bear the distinguishing characteristics of lake deposits; units 2 and 4 show dominantly the irregular bedding, nonpersistence of layers, and variety of physical constitution that are typical of flood-plain and channel deposits…In general, the North Horn strata constitute a record of rapidly shifting flood-plain and lacustrine conditions” (Spieker 1946, page 133). Like the Ojo Alamo Formation of New Mexico, the North Horn Formation straddles the late Cretaceous and the Paleocene Epoch of the Paleogene Period, with Edmund Spieker noting that dinosaur bones are only found within the lower third of the formation. With regards to the Cretaceous strata, he said that it was probably equivalent in age to other geologic formations dating to the uppermost Cretaceous including the Ojo Alamo Formation (Spieker 1946, pages 132-135). The sauropod specimen which was found at North Horn Mountain consisted of a left scapula and coracoid, a right humerus, ulna, radius, and five metacarpals, left and right sternal plates, parts of three ribs, left and right ischia, five sacral vertebrae, and a nearly-complete tail consisting of thirty vertebrae and twenty-five chevrons (Gilmore 1946, page 30). Other bones found at the spot were identified as belonging to ceratopsians, hadrosaurs, turtles, and crocodiles (Spieker 1946, page 134). In 1938, Charles W. Gilmore published a brief note about this discovery (Gilmore 1938, pages 299-300). Earlier, when Charles W. Gilmore reported that sauropod bones had been found in North America within rocks dating to the late Cretaceous, his announcement was met with doubt. In answer to his critics, Gilmore satisfactorily retorted “It should be recalled that Alamosaurus was the first sauropod dinosaur to be recognized from the Upper Cretaceous of North America, and the skepticism with which that announcement was received may now be dissipated by this second discovery under circumstances that are even more convincing than the first, if that is necessary. This specimen will be fully described and discussed as soon as the bones have been prepared for study” (Gilmore 1938, pages 299). You can almost see his smug smirk and hear him say “I told you so”. Charles W. Gilmore got to work writing a full description of the sauropod remains from central Utah, and also comparing them to the bones that had been found in New Mexico in 1916 and 1921. This report was published in 1946 after his death. In it, he asserted that all of the bones had to belong to the genus Alamosaurus (Gilmore 1946, pages 29-41).

Excavating the Alamosaurus arm (collection ID code: USNM 15560) within the North Horn Formation of central Utah. Gilmore 1946, Plate 4.

While Gilmore was in the middle of preparing and describing the fossils which were found in Utah, the American Museum of Natural History sent a paleontological expedition to Texas in late July 1940 jointly led by the famed dinosaur hunter Barnum Brown and the up-and-coming paleontologist Roland T. Bird. The party explored the area of Glenn Springs south of the Chisos Mountains, where the rock layers of the Aguja Formation are found. The expedition also explored the areas on and adjacent to Tornillo Flat. Within Big Bend National Park in Brewster County, Texas, the group discovered a multitude of fossils. Afterwards, the party went to the Paluxy River near the town of Glen Rose to examine and collect portions of the famous dinosaur footprint trackway there. The work was wrapped up on November 30, 1940. On December 11, Barnum Brown attended a meeting of the New York Academy of Science in which he discussed his role as a scientific advisor for the “Rite of Spring” segment in the Walt Disney film Fantasia (Brown 1941, pages 102-105; Maxwell et al. 1967, pages 96, 158-159). During this address, he made some remarks about the paleontological expedition that he had undertaken to Texas earlier that year, in which he said the following…

“In all, eleven important specimens were excavated in this region, among which the following are the most noteworthy: An incomplete but enormous crocodile skull having teeth three inches long and one inch in diameter (probably Dinosuchus) (sic), which was as large as a medium-sized dinosaur; A disarticulated skull with associated limb-bones of a small ceratopsian, resembling and closely related to Brachyceratops; Another incomplete ceratopsian skull, tentatively referred to Pentaceratops; A ceratopsian pelvis, sacrum, and part of the dorsal series with ribs attached (probably Pentaceratops) which was the only articulated specimen found; A complete skull of a new genus and species of a plated dinosaur resembling Palaeoscincus. The dinosaurs collected by us and specimens seen in other collections at El Paso and the Oklahoma University represent a faunal facies comparable in age to that of the Judith River and the Mesa Verde Cretaceous of northern states, but most genera and probably all species are new to science. Two very large sauropod bones – a humerus and a cervical vertebra (Alamosaurus) – were excavated from the Tornillo beds, the vertebra being the largest cervical that has been recorded. The sauropod dinosaurs found in the Tornillo beds show that climatic conditions favorable for the life of sauropods persisted in this southern region millions of years after that group of dinosaurs had become extinct in the northern states. From the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic strata examined, many invertebrate specimens were collected, some being of unusual exhibition value” (Brown 1941, page 104).

The “Tornillo beds” has since been renamed to the Javelina Formation (Maxwell et al. 1967, pages 96, 159).

In the 1960s, a single titanosaur tail vertebra (collection ID code: UALP 4005) was found in Adobe Canyon in the Santa Rita Mountains of southern Arizona. The rocks here belong to the Upper Transitional Unit of the Fort Crittinden Formation. This rock layer is dated to the latter part of the Campanian Stage, about 75-74 MYA. Although this vertebra might belong to Alamosaurus, it was noted that titanosaurid caudal vertebrae tend to look similar amongst different genera, so Robert McCord decided to play it safe and ascribe the vertebra to “Titanosauridae, genus and species indeterminate”. It was reported that this tail vertebra was the oldest titanosaurid fossil known from North America (McCord 1997, page 620; Sullivan and Lucas 2000, page 401), but a subsequent report published in 2010 states that these remains actually belonged to a hadrosaur (D’Emic and Wilson 2010, pages 486-490).

In 1965, it was reported by Ross Maxwell and John W. Dietrich that Alamosaurus bones had been found within the Hell Creek Formation in Petroleum County, Montana (Maxwell and Dietrich 1965). This claim was repeated by Maxwell and his colleagues in 1967 (Maxwell et al. 1967, page 96). However, in both instances, no further information was given – no list of bones found, no collection ID codes, nothing – and no other authors have mentioned anything about it since then. Therefore, Maxwell’s claim is of dubious validity. It’s possible that the bones which seem to have been very hurriedly ascribed to Alamosaurus might have belonged to some other genus.

In 1970, Robert Evan Sloan reported an Alamosaurus hind limb which was found in the Lance Formation at Lance Creek, Wyoming back in the 1920s (Sloan 1970, page 431). However, both the identity and the stratum that the bone was found were doubted because of the specimen’s questionable provenance and also because no sauropod bones of any sort had been found within the Lance Formation before this and up to 1989 (Lucas and Hunt 1989, page 78). It’s possible that this bone was actually found within the Morrison Formation, not the Lance Formation, and belongs to the Kimmeridgian-aged dicraeosaurid sauropod Dyslocosaurus (“Your Friends The Titanosaurs, part 33.2: Alamosaurus of Utah and points north?”). If these fossils were mis-identified and actually belonged to a dicraeosaurid, then it’s possible that they could also belong to the dicraeosaurid Suuwassea (Harris and Dodson 2004, pages 197-210) or to the recently-named Tithonian-aged dicraeosaurid Athenar (Whitlock et al. 2025: a50).

In 1981, Spencer G. Lucas wrote of three titanosaur caudal vertebrae which were found in the late 1970s south of Round Mountain in southwestern Wyoming. The rock layer which these bones were found in comes from the Evanston Formation, which straddles the Cretaceous/Paleogene boundary. It was reported in 1981 and 1989 that these vertebrae were housed in the University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP) in Berkeley (Lucas 1981, page 377; Lucas and Hunt 1989, page 76). I wrote to Dr. Patricia A. Holroyd of the UCMP about these fossils, and I received a response e-mail from her on November 5, 2025 in which she stated unequivocally that the museum has no vertebrate fossils of any sort from Wyoming’s Evanston Formation, nor do they have any documentation that any such fossils were ever collected, nor do they have any such fossils labeled under any other late Cretaceous formations. She also stated that I am not the only person who’s been inquiring about these fossils, which makes me wonder what happened to them.

That same year, Richard Lozinsky was conducting a geological survey on the eastern side of the Elephant Butte Reservoir in Sierra County, New Mexico. The rocks here belonged to the McRae Formation, which is divided into the lower Jose Creek Member. During this survey, Richard Lozinsky found fragments of dinosaur bones. That in itself was nothing new, as fossils had been found here before which were believed to come from Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus. Two of the fossils which were found were a sauropod right humerus measuring 96 cm long (collection ID code: TKM007) and a left femur 168 cm long (collection ID code: TKM009), which were tentatively ascribed under Alamosaurus sp., meaning “Alamosaurus, species unknown”. Both fossils were found close to the boundary separating the Jose Creek Member from the Hall Lake Member (Lozinsky et al. 1984, pages 72-77; Wolberg et al. 1986, pages 227-234).

In the summer of 1984, three Alamosaurus vertebrae were collected by Jess Hunley in the San Juan Basin. It was stated that these bones were found within the De-Na-Zin Member of the Kirtland Formation, which dates to the end of the Campanian Stage of the Cretaceous Period approximately 73 MYA (Sullivan and Lucas 2000, pages 400-403; Williamson and Weil 2008, page 1,218), but it’s now believed that the rock layers were mis-identified and actually come from the overlying Naashoibito Member (Williamson and Weil 2008, pages 1,218-1,223). The Naashoibito Member was long-held to belong to the Ojo Alamo Formation, but Williamson and Weil stated that the Ojo Alamo Formation exclusively dates to the Paleocene Epoch of the Paleogene Period, and therefore the Naashoibito Member belongs to the underlying and older Kirtland Formation (Williamson and Weil 2008, page 1,218). “The San Juan Basin preserves terrestrial deposits that were laid down during the final regression of the Western Interior Seaway during the Late Cretaceous. These strata are placed in the Fruitland and overlying Kirtland Formations. In the Bisti/De-na-zin Wilderness Area of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico (Fig. 1), the Kirtland Formation is subdivided into several members; the Hunter Wash, Farmington Sandstone, De-na-zin, and Naashoibito Members. The Paleocene Ojo Alamo Sandstone overlies the Naashoibito Member in the study area. The strata included in the Naashoibito Member were considered to be part of the Ojo Alamo Sandstone by Bauer (1916) and by Reeside (1924), but Baltz et al. (1966) placed them as a separate member within the Kirtland Formation” (Williamson and Weil 2008, page 1,218). The exact stratigraphic placement of the Naashoibito Member is still contentious.

In the 1990s, a partial skeleton of a juvenile Alamosaurus (collection ID code: TTM 43621-1) was found in Big Bend National Park in Texas. It was recovered from the Black Peaks Formation, fifty meters above this formation’s contact with the underlying Javelina Formation, and is also just two meters below the end-Cretaceous boundary. This shows that Alamosaurus persisted in North America right up to the end of the Cretaceous Period (Lehman and Coulson 2002, pages 156-172). In the spring of 1995, a paleontology class from the University of Texas at Dallas (UTD) was on a field trip in Big Bend National Park to examine the late Cretaceous strata which were exposed there. During this excursion, the students discovered sauropod bones within the Javelina Formation. Over a year later in the winter of 1996, a team composed of members of the University of Texas at Dallas and the Dallas Museum of Natural History excavated the bones, which were shown to belong to one adult and two half-sized juveniles. These bones were provisionally identified as belonging to Alamosaurus (Fiorillo 1998, pages 29-31; Carter et al. 1999, page A4; Coulson and Lehman 1999, page A5; Lucas and Sullivan 2000, page 149).

In addition to being found within the United States, Alamosaurus might have also lived south of the border. A partial skeleton of a sauropod dinosaur, measuring about 22 meters (72 feet) long was found within the Javelina Formation in northwestern Chihuahua, Mexico. It was put on display in the Museo de Paleontología de Delicias, in Delicias, Chihuahua. A preliminary study showed that it was a titanosaurid and the vertebrae were similar to those of Alamosaurus, but at the moment it is unclear if this animal was definitely Alamosaurus or some other genus. Further detailed study is needed (Rivera-Sylva and Carpenter 2014, page 152).

Partial skeleton of a sauropod dinosaur (possibly Alamosaurus) in the Museo de Paleontología de Delicias, in Delicias, Chihuahua, Mexico. Rivera-Sylva and Carpenter 2014, page 153.

Anatomy

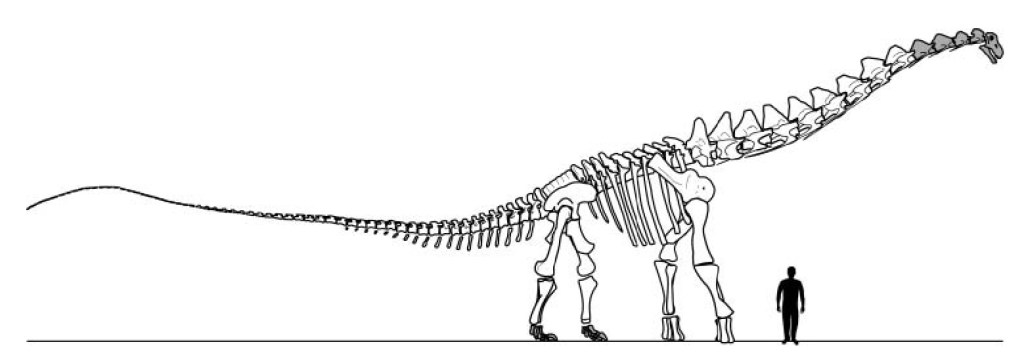

Due to the incompleteness of the remains, size estimates for Alamosaurus range widely from 70 to 100 feet long. In many cases, the size estimates for prehistoric animals start off large, but then steadily get smaller and smaller with subsequent publications. However, with Alamosaurus, the opposite seems to be the case. Sources from the early 1990s give a length estimate of 21 meters (70 feet) (Lambert 1990, page 39; Lessem and Glut 1993, page 12). However, as the years have gone by, Alamosaurus’ size got progressively larger! In 2007, Thomas Holtz Jr. hypothesized that Alamosaurus could have weighed up to 30 tons, but he didn’t provide a length estimate (Holtz Jr. 2007, page 210). In 2011, it was proposed that Alamosaurus might be the largest dinosaur that ever roamed North America during the Cretaceous Period, in the same league as Argentinosaurus and Puertasaurus both of which measured over 100 feet long (Fowler et al. 2011, pages 685-690). In 2013, Scott Hartman hypothesized that Alamosaurus may have reached 28-30 meters (92-98 feet) long (“Assessing Alamosaurus”). A webpage from the National Park Service states that Alamosaurus measured 100 feet long (“Big Bend National Park, Texas”). Gregory Paul said in 2024 that Alamosaurus measured 80 feet long (Paul 2024, page 259).

Yet despite Alamosaurus’ immense size, it may have been surprisingly light on its feet. An examination of the structure of Alamosaurus’ bones show that they were very porous and full of air pockets, even more so than other titanosaurs. This means that despite the creature’s massive size, it actually weighed much less than you would at first suppose (Woodward and Lehman 2009, pages 807-821). That being said, it still likely weighed several dozen tons and you would definitely not like standing in its way!

No skull of Alamosaurus has been found, but we do have several teeth which have been assigned to it. These teeth are very similar to the long peg-like teeth of diplodocid sauropods from the Jurassic Period, which were believed to strip vegetation from stems (Kues et al. 1980, pages 864-869; Sullivan and Lucas 2000, pages 400-403). However, the titanosaurs are not directly related to the diplodocids, but are instead descended from the macronarians, and therefore are actually more closely related to creatures like Camarasaurus and Brachiosaurus. The similarity in titanosaurs’ tooth structure with those of diplodocids is ascribed to convergent evolution (Salgado et al. 1997, pages 3-32). These teeth are also similar in shape to some titanosaurian sauropods like Tapuiasaurus of Brazil and Nemegtosaurus of Mongolia.

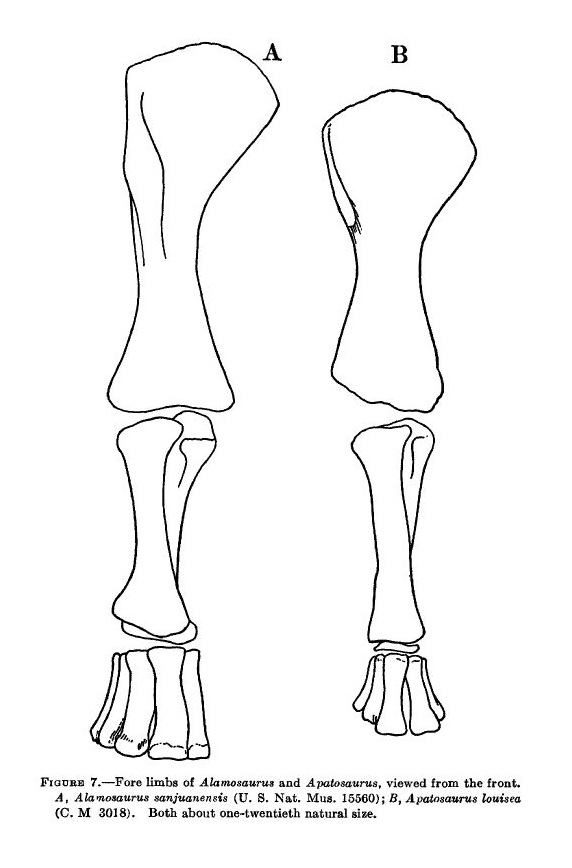

Alamosaurus’ front legs are characteristic of titanosaurs. The humerus was massively built and was longer than the ulna and radius. In other sauropods, such as the diplodocids and the brachiosaurs, the lower arm bones are either the same length as the humerus or they’re longer. Alamosaurus’ metacarpal bones were rather large in proportion to the arm’s overall size, and like other large sauropods like Brachiosaurus, they were arranged into a columnar tube to provide increased weight-bearing support. But the dead giveaway that Alamosaurus was not just a titanosaur but a highly-derived titanosaur was that it had no finger bones, none at all; it walked on its knuckles. Over the years, many sauropods lost the fingers on their hands, being regarded as superfluous. Early titanosaurs like Diamantinasaurus still had some fingers, albeit being reduced to nothing more than small nubs on the end of the hand. However, more derived titanosaurs such as the saltasaurids, which Alamosaurus is believed to have been a member of (more about this later) lost the fingers completely.

The forelimb of Alamosaurus (left) compared with Apatosaurus (right). Note that Alamosaurus’ humerus is substantially larger than its radia and ulnus, and how massively built its manus is. These are proportions that are also seen in the Mongolian late Cretaceous sauropod Opisthocoelicaudia. Gilmore 1946, page 37.

When Saltasaurus was discovered in the late Cretaceous rocks of Argentina, it made a sensation for being the first sauropod dinosaur discovered with body armor. Along its back were a series of small oval-shaped osteoderms which gave it a certain degree of protection against predators. Similar osteoderms were also found in Europe, South America, and Madagascar which were ascribed to titanosaurs from those areas, but no such features were seen in Alamosaurus. Then in 1937, a single osteoderm was found in association with Alamosaurus bones near North Horn Mountain, Utah. This osteoderm had been collected along with the bones, but it had been broken into three pieces and it was embedded within matrix. It wasn’t until the 2010s that researchers realized what these fossil fragments actually were. However, it’s still unknown how extensive these osteoderms were on Alamosaurus’ body (Carrano and D’Emic 2015: e901334).

Skeletal drawing of Alamosaurus sanjuanensis based on BIBE 45854, TMM 41541-1, USNM 15560 and the distal caudal series of an as-yet-unnamed South American titanosaur. Human silhouette represents a 1.8 m tall individual. Grey elements are missing, and are reconstructed based upon other similar titanosaur species. Tykoski and Fiorillo 2017, page 341.

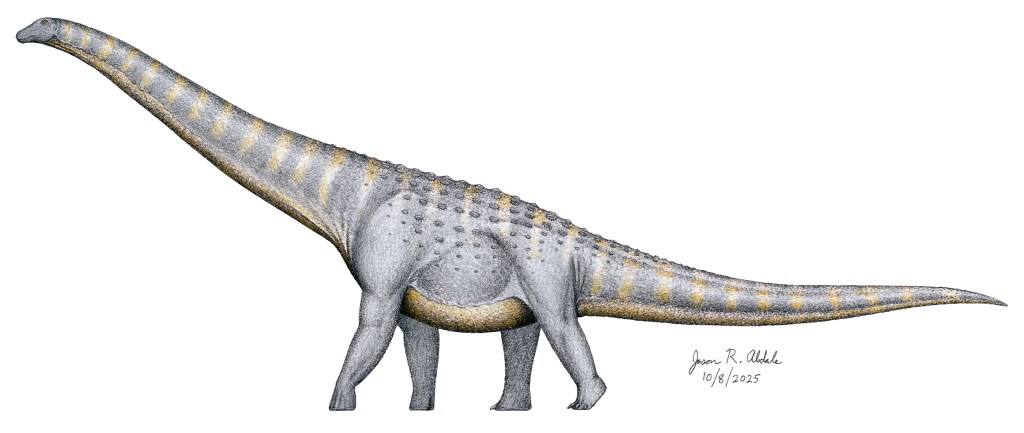

Alamosaurus sanjuanensis. © Jason R. Abdale (October 8, 2025).

Phylogeny and the end of North America’s “sauropod hiatus”

In 1927, the German paleontologist Friedrich von Huene (who is most known for his work on the late Triassic prosauropod dinosaur Plateosaurus) tentatively assigned Alamosaurus to the sauropod family Titanosauridae (Von Huene 1927, page 469). Named after the eponymous Titanosaurus indicus of India, the titanosaurs emerged during the middle Cretaceous Period, and they became the major sauropod group during the late Cretaceous inhabiting South America, Africa, Europe, Asia, and Australia. They include some of the largest dinosaurs that ever lived, such as Argentinosaurus and Patagotitan. However, von Huene provided no evidence for putting Alamosaurus into Titanosauridae. In 1929, von Huene repeated his cautious assignment of Alamosaurus to Titanosauridae (Von Huene 1929, page 118), but also made the following remarks: Sieht man auf die fauna, so ist es in det tat interessant, dass die in Südamerika so zahlreich vorbandenen Titanosauriden in Nordamerika fast unbekannt sind. Nur Alamosaurus in New Mexiko durfte in diese familie gehoren, “Looking at the fauna, it is interesting that the titanosaurids, which are so numerous in South America, are almost unknown in North America. Only Alamosaurus in New Mexico was considered to belong to this family” (Von Huene 1929, page 185). Even so, Von Huene was skeptical that Alamosaurus was a South American titanosaur which migrated north into North America, stating that there was no geological evidence of a land bridge connecting these two continents during the late Cretaceous (Von Huene 1929, page 185).

In 1938, Charles W. Gilmore published a brief note about the Alamosaurus bones found in Utah in which he, like Von Huene, assigned it to the family Titanosauridae (Gilmore 1938, pages 299-300). Gilmore repeated this in 1946 in which he asserted that Alamosaurus belonged to the family Titanosauridae based upon the structure of the vertebrae (Gilmore 1946, pages 29-30).

While it’s agreed that Alamosaurus was a titanosaurian sauropod, there has been dispute as to where exactly it sits within the titanosaurian tree. The prevailing ideas are:

- Placed within the titanosaurid sub-family Titanosaurinae (Kues et al. 1980, page 867).

- Placed outside the titanosaur family Saltasauridae (Upchurch 1998, pages 75-78; Upchurch et al. 2004, page 297; Carballido et al. 2011, page 633; Carballido and Sander 2014, page 40; Simon et al. 2017, page 27; Tykoski and Fiorillo 2017, pages 354-358; Cerda et al. 2021, page 13; Gorscak et al. 2023: e2199810; Filippi et al. 2024, page 10).

- As a basal member of the family Saltasauridae with no affiliation to any particular sub-family (Lacovara et al. 2014, page 4).

- Within the saltasaurid sub-family Saltasaurinae (Mannion et al. 2014, pages 124, 126-128; Navarro et al. 2022, page 344).

- Within the saltasaurid sub-family Opisthocoelicaudiinae (Lucas and Sullivan 2000, page 147; Wilson 2002, page 240; Wilson 2005, page 20; Curry Rogers 2005, page 71; Calvo et al. 2007a, page 533; Calvo et al. 2007b, page 523; Gonzalez Riga et al. 2009, page 144; Zaher et al. 2011: e16663; Gonzalez Riga and Ortiz 2014, page 20; França et al. 2016: e2054).

- In between the sub-families Saltasaurinae and Opisthocoelicaudiinae, located just outside Saltasaurinae (Salgado et al. 1997, page 25; Gonzalez Riga 2003, page 168; Calvo and Gonzalez Riga 2003, page 342; Saegusa and Ikeda 2014, page 54).

At the end of the Jurassic Period 145 MYA, it appears that all of North America’s native sauropods were wiped out. During the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, a few sauropods including turiasaurids and European brachiosaurids seem to have migrated across a land bridge from Europe and to have repopulated North America (Brikiatis 2016, pages 47-57; Kirkland et al. 2016, pages 138, 154). Some of the last sauropods to live within North America include Astrodon, and Sauroposeidon which lived during the Albian Stage approximately 110 MYA and Abydosaurus and Sonorasaurus which lived around 100-95 MYA. However, after this, sauropods disappeared from North America. It is believed that sauropods were totally extirpated from the continent, despite continuing to survive elsewhere, especially in South America. Sauropods don’t appear in the fossil record within North America until the sudden appearance of the titanosaurian Alamosaurus during the Maastrichtian Stage. All of the formations which Alamosaurus is found in date to the Maastrichtian Stage. Claims which were made that titanosaurian sauropods existed in North America during the early Cretaceous were disproven (D’Emic and Foreman 2012, page 897). This roughly thirty million year long gap in the fossil record is referred to as “the sauropod hiatus” (Lucas and Hunt 1989, pages 75-86).

This naturally leads one to ask where Alamosaurus came from. Due to its supposed close affinities with the Mongolian titanosaur Opisthocoelicaudia, it’s possible that Alamosaurus or its ancestors were of Asian ancestry and migrated into North America across the north Pacific land bridge at the end of the Cretaceous Period along with tyrannosaurs and ceratopsians. However, it seems that Alamosaurus was actually more closely related to South American titanosaurs, as was initially supposed (Lucas and Hunt 1989, page 78; Lehman and Coulson 2002, page 169; Cerda et al. 2021, page 13). In particular Fronimos and Lehman stated in 2014 that Alamosaurus bears the closest resemblance to the Brazilian titanosaurs Trigonosaurus pricei, Uberabatitan riberoi, and Baurutitan britoi (Fronimos and Lehman 2014, page 896). Geological evidence suggests that a land bridge connecting North and South America formed during the Campanian or Maastrichtian Stages of the Late Cretaceous Period (Anderson and Schmidt 1983, pages 961-963; Lucas and Hunt 1989, page 83). This would have allowed South American titanosaurs to move northwards, and likewise would have allowed North American hadrosaurs to move southwards, as several hadrosaur genera have been found in South America which are closely related to the North American genus Kritosaurus. This time frame would also explain why no sauropod dinosaurs have been found in North American rocks during the late Cretaceous until the beginning of the Maastrichtian Stage. However, this faunal interchange was short-lived, as the Mesozoic Era came to an end only a few million years afterwards.

Is there more than one North American titanosaur?

For several decades, all sauropod remains which were found in western North America dating to the end of the Cretaceous Period were automatically ascribed to Alamosaurus simply because no other sauropods were known from North America during this time. In 1984, Richard Lozinsky and his colleagues criticized this practice, saying “There is a strong tendency to refer records of Late Cretaceous North American sauropods to Alamosaurus without real justification” (Lozinsky et al. 1984, page 75). Alamosaurus was increasingly running the risk of becoming a “wastebasket taxon”, a genus which fossils of dubious identity tend to get lumped under either as a temporary place-holder or because there are no other options available to choose from.

A large part of the reason why paleontologists did this was because in almost every locality where Alamosaurus remains were found, there were only a few bones here and there. This made it very difficult to cross-reference different bones with each other, especially when there were no duplicates of certain bones; there was only one specimen of this or that bone. How could you be sure if this one-and-only element belonged to Alamosaurus or to some other large sauropod? Well, you couldn’t be sure, that was the problem. By at least the year 2000, it was proposed that the total of titanosaur remains found within North America might belong to more than one species (Lucas and Sullivan 2000, page 150; Fronimos and Leman 2014, page 895). However, until more specimens (preferably reasonably complete ones) could be found, this notion was difficult to prove.

In October 2025, Gregory Paul claimed that the sauropod fossils which were found in central Utah back in the 1930s didn’t come from Alamosaurus after all, and actually belonged to another titanosaurian sauropod which he named Utetitan (Paul 2025, pages 201-220). However, criticisms were immediately raised that the research wasn’t done as thoroughly as it should have been and the arguments which were given in the article were rather lacking. It’s possible that these remains do indeed belong to another sauropod dinosaur which lived in North America at the close of the Cretaceous, but it’s also possible that these fossils belong to Alamosaurus and the noted anatomical differences are purely due to individualistic variation in the shape of the bones. The admittedly unsatisfactory answer that must be given here is “More research is needed”. Personally, I think that every single Alamosaurus bone that has ever been found needs to be analyzed to form a compendium of knowledge about this animal’s anatomy, but that will be an absolutely huge and daunting undertaking. A task for an aspiring paleo PhD, perhaps? Only time will tell.

Conclusion

Regardless of the vague and sometimes contradictory information surrounding Alamosaurus, it cannot be denied that it was a remarkable animal. After a thirty million year absence from North America, the sauropods came back in splendid fashion with a magnificent and thunderous return to the prehistoric stage. Alamosaurus was the largest dinosaur known to inhabit North America during the Cretaceous Period, and it was one of the largest dinosaurs to have existed right at the end of the age of dinosaurs. What a way to go out with a bang.

Bibliography

Books

Holtz Jr., Thomas R. Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. New York: Random House Children’s Books, 2007.

Lambert, David. The Dinosaur Data Book. New York: Avon Books, 1990.

Lessem, Don. Glut, Donald F. The Dinosaur Society Dinosaur Encyclopedia. New York: Random House, Inc., 1993.

Paul, Gregory S. The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Third Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2024.

Articles

Anderson, Thomas H.; Schmidt, Victor A. (1983). “The evolution of Middle America and the Gulf of Mexico-Caribbean Sea region during Mesozoic time”. Geological Society of America Bulletin, volume 94 (1983). Pages 941-966.

https://www.geo.mtu.edu/volcanoes/06upgrade/Seismicity-Rudiger/anderson_schmidt_evolution_central_maerica_mesozoic.pdf.

Brikiatis, Leonidas (2016). “Late Mesozoic North Atlantic land bridges”. Earth-Science Reviews, volume 159 (May 2016). Pages 47-57.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0012825216300794.

Brown, Barnum (1941). “The Methods of Walt Disney Productions. (An extended abstract of an address given at the Annual Dinner and Meeting, December 11, 1940.)”. Transactions of the New York Academy of Science, volume 3, issue 4 (1941). Pages 100-105.

https://archive.org/details/sim_new-york-academy-of-sciences-transactions_1941-02_3_4/page/100/mode/2up?q=Brown.

Calvo, Jorge Orlando; Gonzalez Riga, Bernardo Javier (2003). “Rinconsaurus caudamirus gen. et sp. nov., a new titanosaurid (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina”. Revista Geologica de Chile, volume 30, issue 2 (December 2003). Pages 333-353.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250373494_Rinconsaurus_caudamirus_gen_et_sp_nov_a_new_titanosaurid_Dinosauria_Sauropoda_from_the_Late_Cretaceous_of_Patagonia_Argentina.

Calvo, Jorge Orlando; Porfiri, Juan D.; Gonzalez Riga, Bernardo Javier; Kellner, Alexander Wilhelm Armin (2007a). “A new Cretaceous terrestrial ecosystem from Gondwana with the description of a new sauropod dinosaur”. Anais da Academia Brasiliera de Ciencias, volume 79, issue 3 (2007). Pages 529-541.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6071132_A_new_Cretaceous_terrestrial_ecosystem_from_Gondwana_with_the_description_of_a_new_sauropod_dinosaur.

Calvo, Jorge Orlando; Porfiri, Juan D.; Gonzalez Riga, Bernardo Javier; Kellner, Alexander Wilhelm Armin (2007b). “Anatomy of Futalognkosaurus dukei Calvo, Porfiri, Gonzalez Riga, and Kellner, 2007 (Dinosauria, Titanosauridae) from the Neuquén Group (Late Cretaceous), Patagonia, Argentina”. Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, volume 65, issue 4 (December 2007). Pages 511-526.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237289209_Anatomy_of_Futalognkosaurus_dukei_Calvo_Porfiri_Gonzalez_Riga_Kellner_2007_Dinosauria_Titanosauridae_from_the_Neuquen_Group_Late_Cretaceous_Patagonia_Argentina.

Carballido, Jose L.; Sander, P. M. (2014). “Postcranial axial skeleton of Europasaurus holgeri (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Upper Jurassic of Germany: Implications for sauropod ontogeny and phylogenetic relationships of basal Macronaria”. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, volume 12 (2014). Pages 335-387.

https://www.academia.edu/3394461/Postcranial_axial_skeleton_of_Europasaurus_holgeri_Dinosauria_Sauropoda_from_the_Upper_Jurassic_of_Germany_implications_for_sauropod_ontogeny_and_phylogenetic_relationships_of_basal_Macronaria.

Carballido, Jose L.; Rauhut, Oliver W. M.; Pol, Diego; Salgado, Leonardo (2011). “Osteology and phylogenetic relationships of Tehuelchesaurus benitezii (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Upper Jurassic of Patagonia”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, volume 163 (2011). Pages 605-662.

https://www.academia.edu/1932789/Osteology_and_phylogenetic_relationships_of_Tehuelchesaurus_benitezii_Dinosauria_Sauropoda_from_the_Upper_Jurassic_of_Patagonia_Zoological_Journal_of_the_Linnean_Society_163_605_662.

Carrano, Matthew T.; D’Emic, Michael D. (2015). “Osteoderms of the titanosaur sauropod dinosaur Alamosaurus sanjuanensis Gilmore, 1922”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 35, issue 1 (February 2015): e901334.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272413111_Osteoderms_of_the_Titanosaur_Sauropod_Dinosaur_Alamosaurus_sanjuanensis_Gilmore_1922.

Carter, J. L.; Montgomery, Homer; Biasatti, Dana (1999). “The UTD Alamosaurus sanjuanensis Gilmore find in Big Bend, Texas”. Geological Society of America, Abstracts with Programs, volume 31, issue 1 (1999). Page A4.

Cerda, Ignacio; Zurriaguz, Virginia Laura; Carballido, José Luis; González, Romina; Salgado, Leonardo (2021). “Osteology, paleohistology and phylogenetic relationships of Pellegrinisaurus powelli (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentinean Patagonia”. Cretaceous Research, volume 128 (December 2021). Pages 1-17

Coulson, Alan B.; Lehman, Thomas M. (1999). “A juvenile specimen of Alamosaurus from the Javelina Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Big Bend National Park, Texas”. Geological Society of America, Abstracts with Programs, volume 31, issue 1 (1999). Page A5.

Curry Rogers, Kristina A. (2005). “Titanosauria”. In Curry Rogers, Kristina A.; Wilson, Jeffrey, eds. The Sauropods: Evolution and Paleobiology. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005. Pages 50-103.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Sauropods/X5j2lqAZqwIC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Titanosauria+the+sauropods&pg=PA51&printsec=frontcover.

Dalman, Sebastian; Lucas, Spencer G. (2016). “Frederic Brewster Loomis’ 1924 Amherst College Paleontological Expedition to the San Juan Basin, New Mexico”. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, volume 74 (2016) Pages 61-66.

https://nmdigital.unm.edu/digital/collection/bulletins/id/7088.

D’Emic, Michael D.; Foreman, Brady Z. (2012). “The beginning of the sauropod dinosaur hiatus in North America: Insights from the Lower Cretaceous Cloverly Formation of Wyoming”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 32, issue 4 (July 2012). Pages 883-902.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258567431_The_beginning_of_the_sauropod_dinosaur_hiatus_in_North_America_insights_from_the_Lower_Cretaceous_Cloverly_Formation_of_Wyoming.

D’Emic, Michael D.; Wilson, Jeffrey A.; Thompson, Richard (2010). “The end of the sauropod dinosaur hiatus in North America”. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, volume 297 (September 2010). Pages 486-490.

https://www.geo.arizona.edu/xtal/group/pdf/PPP297_486.pdf.

Filippi, Leonardo S.; Juárez Valieri, Rubén D.; Gallina, Pablo A.; Méndez, Ariel H.; Gianechini, Federico A.; Garrido, Alberto C. (2024). “A rebbachisaurid-mimicking titanosaur and evidence of a Late Cretaceous faunal disturbance event in South-West Gondwana”. Cretaceous Research, volume 154, volume 3 (February 2024). Page 1-14.

Fiorillo, Anthony R. (1998). “Preliminary report of a new sauropod locality in the Javelina Formation (Late Cretaceous), Big Bend National Park, Texas”. In Santucci, V. L.; McClelland, L., eds. National Park Service Paleontological Research, technical report NPS/NRGRD/GRDTR-98/1 (1998). Pages 29-31.

https://npshistory.com/publications/paleontology/grdtr-98-01.pdf.

Fowler, Denver W.; Sullivan, Robert M. (2011). “The First Giant Titanosaurian Sauropod from the Upper Cretaceous of North America”. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, volume 56, issue 4 (2011). Page 685.

https://www.app.pan.pl/archive/published/app56/app20100105.pdf.

França, Marco A. G.; Marsola, Julio C. d A.; Riff, Douglas; Hsiou, Annie S.; Langer, Max C. (2016). “New lower jaw and teeth referred to Maxakalisaurus topai (Titanosauria: Aeolosaurini) and their implications for the phylogeny of titanosaurid sauropods”. PeerJ, volume 4: e2054 (June 8, 2016).

https://peerj.com/articles/2054/.

Fronimos, John A.; Lehman. Thomas M. (2014). “New specimens of a titanosaur sauropod from the Maastrichtian of Big Bend National Park, Texas”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 34, issue 4 (July 2014). Pages 883-899.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264090872_New_Specimens_of_a_Titanosaur_Sauropod_from_the_Maastrichtian_of_Big_Bend_National_Park_Texas.

Gilmore, Charles W. (1921). “Discovery of Sauropod Dinosaur Remains in the Upper Cretaceous of New Mexico”. Science, volume 54, issue 1395 (September 23, 1921). Page 274.

https://archive.org/details/science541921mich/page/n5/mode/2up.

Gilmore, Charles W. (1922). “A new sauropod dinosaur from the Ojo Alamo Formation of New Mexico”. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, volume 72, issue 14 (January 31, 1922). Pages 1-9.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/64/A_new_sauropod_dinosaur_from_the_Ojo_Alamo_Formation_of_New_Mexico.pdf.

Gilmore, Charles W. (1938). “Sauropod dinosaur remains in the Upper Cretaceous”. Science, volume 87, issue 2257 (April 1, 1938). Pages 299-300.

https://archive.org/details/sim_science_1938-04-01_87_2257.

Gilmore, Charles W. (1946). “Reptilian fauna of the North Horn Formation of Central Utah”. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 210-C. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1946. Pages 29-51.

https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/0210a/report.pdf.

Gorscak, Eric; Lamanna, Matthew C.; Schwarz, Daniela; Díez Díaz, Verónica; Salem, Belal S.; Sallam, Hesham M.; Wiechmann, Marc Filip (2023). “A new titanosaurian (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) Quseir Formation of the Kharga Oasis, Egypt”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 42, issue 6: e2199810 (July 20, 2023).

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372540224_A_new_titanosaurian_Dinosauria_Sauropoda_from_the_Upper_Cretaceous_Campanian_Quseir_Formation_of_the_Kharga_Oasis_Egypt.

Gonzalez Riga, Bernardo Javier (2003). “A new titanosaur (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mendoza Province, Argentina”. Ameghiniana, volume 40, issue 2 (June 30, 2003). Pages 155-172.

https://www.ameghiniana.org.ar/index.php/ameghiniana/article/download/951/1714.

Gonzalez Riga, Bernardo Javier; Ortiz, David, L. (2014). “A new titanosaur (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous (Cerro Lisandro Formation) of Mendoza Province”. Argentina. Ameghiniana, volume 51, issue 1 (February 2014). Pages 3-25.

https://bioone.org/journals/Ameghiniana/volume-51/issue-1/AMEGH.26.12.1013.1889/A-New-Titanosaur-Dinosauria-Sauropoda-from-the-Upper-Cretaceous-Cerro/10.5710/AMEGH.26.12.1013.1889.short.

Gonzalez Riga, Bernardo Javier; Previtera, Elena; Pirrone, Cecilia A. (2009). “Malarguesaurus florenciae gen. et sp. nov., a new titanosauriform (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mendoza, Argentina”. Cretaceous Research, volume 30 (2009). Pages 135-148.

https://www.academia.edu/91443868/Malarguesaurus_florenciae_gen_et_sp_nov_a_new_titanosauriform_Dinosauria_Sauropoda_from_the_Upper_Cretaceous_of_Mendoza_Argentina.

Harris, Jerald D.; Dodson, Peter (2004). “A new diplodocoid sauropod dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Montana, USA”. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, volume 49, issue 2 (2004). Pages 197-210.

https://www.app.pan.pl/archive/published/app49/app49-197.pdf.

Kirkland, James I.; Suarez, Marina; Suarez, Celina; Hunt-Foster, ReBecca (2016). “The Lower Cretaceous in East-Central Utah—The Cedar Mountain Formation and its Bounding Strata”. Geology of the Intermountain West, volume 3 (October 2016). Pages 101-228.

https://giw.utahgeology.org/giw/index.php/GIW/article/view/11.

Kues, Barry S.; Lehman, Thomas M.; Rigby Jr., J. Keith (1980). “The teeth of Alamosaurus sanjuanensis, a Late Cretaceous sauropod”. Journal of Paleontology, volume 54, issue 4 (July 1980). Pages 864-869.

Lacovara, Kenneth J.; Lamanna, Matthew C.; Ibiricu, Lucio Manuel; Poole, Jason C.; Schroeter, Elena R.; Ullmann, Paul V.; Voegele, Kristyn K.; Boles, Zachary M.; Carter, Aja M.; Fowler, Emma K.; Egerton, Victoria M.; Moyer, Alison E.; Coughenour, Christopher L.; Schein, Jason P.; Harris, Jerald D.; Martinez, Rubén Darío Francisco; Novas, Fernando E. (2014). “A gigantic, exceptionally complete titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur from southern Patagonia, Argentina”. Nature, Scientific Reports, volume 4, issue 6196 (September 2014). Pages 1-9.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265377777_A_Gigantic_Exceptionally_Complete_Titanosaurian_Sauropod_Dinosaur_from_Southern_Patagonia_Argentina.

Lehman, Thomas M. (1985). “Depositional environments of the Naashoibito Member of the Kirtland Formation, Upper Cretaceous, San Juan Basin, New Mexico”. New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, Circular 195: Contributions to Late Cretaceous Paleontology and Stratigraphy of New Mexico, Part 1 (April 1985). Pages 55-79.

https://geoinfo.nmt.edu/publications/monographs/circulars/downloads/195/Circular-195.pdf.

Lehman, Thomas M.; Coulson, Alan B. (2002). “A juvenile specimen of the sauropod Alamosaurus sanjuanensis from the Upper Cretaceous of Big Bend National Park, Texas”. Journal of Paleontology, volume 76, issue 1 (January 2002). Pages 156-172.

https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/paleosoc/jpaleontol/article-abstract/76/1/156/83378/A-JUVENILE-SPECIMEN-OF-THE-SAUROPOD-DINOSAUR?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

Lozinsky, Richard P.; Hunt, Adrian P.; Wolberg, Donald L.; Lucas, Spencer G. (1984). “Late Cretaceous (Lancian) dinosaurs from the McRae Formation, Sierra County, New Mexico”. New Mexico Geology, volume 6, issue 4 (November 1984). Pages 72-77.

https://geoinfo.nmt.edu/publications/periodicals/nmg/6/n4/nmg_v6_n4_p72.pdf.

Lucas, Spencer G. (1981) “Dinosaur communities in the San Juan Basin: A case for lateral variations in the composition of Late Cretaceous dinosaur communities”. In Lucas, Spencer G.; Rigby Jr., J. Keith; Kues, Barry S., eds. Advances in San Juan Basin Paleontology. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1981. Pages 337-393.

Lucas, Spencer G.; Hunt, Adrian P. (1989). “Alamosaurus and the Sauropod Hiatus in the Cretaceous of the North American Western Interior”. Paleobiology of the Dinosaurs. Geological Society of America Special Papers, 238 (1989). Pages 75-86.

Lucas, Spencer G.; Sullivan, Robert M. (2000). “The Sauropod Dinosaur Alamosaurus from the Upper Cretaceous of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico”. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, no. 17 (2000). Pages 147-156.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Dinosaurs_of_New_Mexico/gV8fCgAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Alamosaurus&pg=PA147&printsec=frontcover.

Mannion, Philip D.; Upchurch, Paul; Barnes, Rosie N.; Mateus, Octavio (2013). “Osteology of the Late Jurassic Portuguese sauropod dinosaur Lusotitan atalaiensis (Macronaria) and the evolutionary history of basal titanosauriforms”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, volume 168 (May 2013). Pages 98-206.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260793820_Osteology_of_the_Late_Jurassic_Portuguese_sauropod_dinosaur_Lusotitan_atalaiensis_Macronaria_and_the_evolutionary_history_of_basal_titanosauriforms.

Mateer, Niall J. (1976). “New topotypes of Alamosaurus sanjuanensis Gilmore (Reptilian: Sauropoda)”. Bulletin of the Geological Institutions of the University of Uppsala, volume 6 (1976). Pages 93-95.

https://paleoarchive.com/literature/Mateer1976-NewTopotypesAlamosaurusSanjuanensisGilmore.pdf.

Maxwell, Ross A.; Dietrich, John W. (1965). “West Texas Geological Society Publication 65-51: Geology of the Big Bend area, Texas – Field trip guidebook with road log and papers on natural history of the area”. Midland: West Texas Geological Society, 1965. Pages 1-196.

Maxwell, Ross A.; Lonsdale, John T.; Hazzard Roy T.; Wilson, John A. (1967). “Geology of Big Bend National Park, Brewster County, Texas”. The University of Texas, publication no. 6711 (June 1, 1967). Pages 1-320.

https://archive.org/details/geologyofbigbend00maxw/mode/2up.

McCord, Robert D. (1997). “An Arizona titanosaurid sauropod and revision of the Late Cretaceous Adobe fauna”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 17, issue 3 (September 4, 1997). Pages 620-622.

Navarro, Bruno A.; Ghilardi, Aline M.; Aureliano, Tito; Díaz, Verónica Díez; Bandeira, Kamila L. N.; Cattaruzzi, André G. S.; Iori, Fabiano V.; Martine, Ariel M.; Carvalho, Alberto B.; Anelli, Luiz E.; Fernandes, Marcelo A.; Zaher, Hussam (2022). “A new nanoid titanosaur (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Brazil”. Ameghiniana, volume 59, issue 5 (September 15, 2022). Pages 317-354.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362978138_A_new_nanoid_titanosaur_Dinosauria_Sauropoda_from_the_Upper_Cretaceous_of_Brazil.

Paul, Gregory S. (2025). “Stratigraphic and anatomical evidence for multiple titanosaurid dinosaur taxa in the Late Cretaceous (Campanian-Maastrichtian) of southwestern North America”. Geology of the Intermountain West, volume 12 (October 7, 2025). Pages 201-220.

https://giw.utahgeology.org/giw/index.php/GIW/article/view/156.

Rivera-Sylva, Hector E.; Carpenter, Kenneth (2014). “Mexican Saurischian Dinosaurs”. In Rivera-Sylva, Hector E.; Carpenter, Kenneth; Frey, Eberhard, eds. Dinosaurs and other Reptiles from the Mesozoic of Mexico. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014. Pages 143-155.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285749512_Mexican_saurischian_dinosaurs.

Saegusa, Haruo; Ikeda, Tadahiro (2014). “A new titanosauriform sauropod (Dinosauria: Saurischia) from the Lower Cretaceous of Hyogo, Japan”. Zootaxa, volume 3848, issue 1 (August 12, 2014). Pages 1-66.

https://www.biotaxa.org/Zootaxa/article/view/zootaxa.3848.1.1.

Salgado, Leonardo; Coria, Rodolfo A.; Calvo, Jorge Orlando (1997). “Evolution of the titanosaurid sauropods. I: phylogenetic analysis based on the postcranial evidence”. Ameghiniana, volume 34, issue 1 (April 15, 1997). Pages 3-32.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283797197_Evolution_of_titanosaurid_sauropods_I_Phylogenetic_analysis_based_on_the_postcranial_evidence.

Simon, Edith; Salgado, Leonardo; Calvo, Jorge Orlando (2017). “A New Titanosaur Sauropod from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, Neuquén Province, Argentina”. Ameghiniana, volume 55, issue 1 (January 2017). Pages 1-29.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318931668_A_New_Titanosaur_Sauropod_from_the_Upper_Cretaceous_of_Patagonia_NeuqueN_Province_Argentina.

Sloan, R. E. (1970). “Cretaceous and Paleocene terrestrial communities of western North America”. In Yochelson, Ellis L., ed. Proceedings of the North American Paleontological Convention, Chicago, September 5-7, 1969, volume 1, part E. Lawrence: Allen Press, 1970. Pages 427-453.

Spieker, Edmund M. (1946). “Late Mesozoic and early Cenozoic history of central Utah”. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 205-D. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1946. Pages 134-135.

https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/0205d/report.pdf.

Sullivan, Robert M.; Lucas, Spencer G. (2000). “Alamosaurus (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Late Campanian of New Mexico and its significance”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 20, issue 2 (June 2000). Pages 400-403.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232676153_Alamosaurus_Dinosauria_Sauropoda_from_the_late_Campanian_of_New_Mexico_and_its_significance.

Sullivan, Robert M.; Lucas, Spencer G.; Braman, Dennis R. (2005). “Dinosaurs, pollen, and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary in the San Juan Basin, New Mexico”. 56th Fall Field Conference Guidebook, New Mexico Geological Society (January 2005). Pages 395-407.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266228740_Dinosaurs_pollen_and_the_Cretaceous-Tertiary_boundary_in_the_San_Juan_Basin_New_Mexico.

Tykoski, Ronald S.; Fiorillo, Anthony R. (2017). “An articulated cervical series of Alamosaurus sanjuanensis Gilmore, 1922 (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from Texas: New perspective on the relationships of North America’s last giant sauropod”. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, volume 15, issue 5 (2017). Pages 339-364.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/14772019.2016.1183150?needAccess=true.

Upchurch, Paul (1998). “The phylogenetic relationships of sauropod dinosaurs”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, volume 124 (1998). Pages 43-103.

https://doc.rero.ch/record/14454/files/PAL_E1644.pdf.

Upchurch, Paul; Barrett, Paul M.; Dodson, Peter (2004). “Sauropoda”. In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmolska, Halszka, eds. The Dinosauria, 2nd Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. Pages 259-322.

https://archive.org/details/epdf.pub_the-dinosauria-2nd-edition.

Von Huene, Friedrich (1927). “Sichtung der Grundlagen der jetzigen Kenntnis der Sauropoden”. Eclogae Geologicae Helveticae, volume 20 (1927). Pages 444-470.

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/43660279.pdf.

Von Huene, Friedrich (1929). “Los saurisquios y ornitisquios del Cretáceo Argentino”. Anales del Museo de La Plata, volume 3 (1929). Pages 1-196.

https://dinodata.de/bibliothek/pdf_l/1929/001_vonHuene_camplo_dd.pdf.

Whitlock, John A.; Garderes, Juan Pablo; Gallina, Pablo; Lamanna, Matthew C. (2025). “Athenar bermani, a new species of dicraeosaurid sauropod from Dinosaur National Monument, Utah, U.S.A.”. Palaeontologia Electronica, volume 28, issue 3: a50 (October 27, 2025).

https://palaeo-electronica.org/content/2025/5682-athenar-bermani-new-dicraeosaurid-sauropod.

Williamson, Thomas E.; Weil, Anne (2008). “Stratigraphic distribution of sauropods in the Upper Cretaceous of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico, with comments on North America’s Cretaceous ‘Sauropod Hiatus’”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 28, issue 4 (December 1, 2008). Pages 1,218-1,223.

Wilson, Jeffrey A. (2002). “Sauropod dinosaur phylogeny: Critique and cladistic analysis”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, volume 136, issue 2 (September 13, 2002). Pages 217-276.

https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/items/6b6b8257-3d83-4d28-a999-450ff423baab.

Wilson, Jeffrey A. (2005). “Overview of sauropod phylogeny and evolution”. In Curry Rogers, Kristina A.; Wilson, Jeffrey, eds. The Sauropods: Evolution and Paleobiology. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005. Pages 15-49.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Sauropods/X5j2lqAZqwIC?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Wolberg, Donald L.; Lozinsky, Richard P.; Hunt, Adrian P. (1986). “Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian–Lancian) vertebrate paleontology of the McRae Formation, Elephant Butte area, Sierra County, New Mexico”. In Clemons, Russell E.; King, William E.; Mack, Greg H.; Zidek, Jiri, eds. New Mexico Geological Society Fall Field Conference Guidebook 37: Truth or Consequences Region (1986). Pages 227-334.

https://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/downloads/37/37_p0227_p0234.pdf.

Woodward, Holly N.; Lehman, Thomas M. (2009). “Bone histology and microanatomy of Alamosaurus sanjuanensis (Sauropoda: Titanosauria) from the Maastrichtian of Big Bend National Park, Texas”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 29, issue 3 (September 2009). Pages 807-821.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233733738_Bone_Histology_and_Microanatomy_of_Alamosaurus_sanjuanensis_Sauropoda_Titanosauria_from_the_Maastrichtian_of_Big_Bend_National_Park_Texas.

Zaher, Hussam; Pol, Diego; Carvalho, Alberto B.; Nascimento, Paulo M.; Riccomini, Claudio; Larson, Peter; Juarez-Valieri, Ruben; Pires-Domingues, Ricardo; da Silva, Nelso Jorge; Campos, Diógenes de Almeida (2011). “A complete skull of an Early Cretaceous sauropod and the evolution of advanced titanosaurians”. PLoS ONE, volume 6, issue 2: e16663 (February 7, 2011).

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0016663.

Websites

Equatorial Minnesota. “Your Friends The Titanosaurs, part 33.2: Alamosaurus of Utah and points north?”, by Justin Tweet (February 13, 2021).

https://equatorialminnesota.blogspot.com/2021/02/your-friends-titanosaurs-part-332-alamosaurus-utah.html. Accessed on October 17, 2025.

National Park Service. “Big Bend National Park, Texas” (April 27, 2020).

https://www.nps.gov/bibe/learn/nature/alamosaurus.htm. Accessed on October 18, 2015.

Skeletal Drawing. “Assessing Alamosaurus”, by Scott Hartman (June 21, 2013).

https://www.skeletaldrawing.com/home/2013/6/21/assessing-alamosaurus. Accessed on October 18, 2015.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment