Introduction

An infantryman is only as good as his rifle and his feet, and nowhere was this truer than in the jungles and rice paddies of Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War. While much has been written about American firepower and issues with its weaponry, notably the problems plaguing the early-issue M-16 assault rifles, something which has not faced as much scrutiny but which was just as important were problems with footwear.

The Vietnam War lasted from 1956 to 1975, but the United States did not become “officially” involved until the signing of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in August 1964. When the military deployed the first “boots on the ground” in March 1965, the troops often marched off to battle with out-dated obsolete clothing and equipment which were better suited to fighting in eastern Europe against the Red Army. However, the men quickly learned that slugging it out in the hot humid tropical jungles of Southeast Asia would be a different story. In many cases, their gear just didn’t make the cut.

Among the equipment worn and carried by these young green troopers which was in serious need of revamping were their boots. American military personnel first deployed to Vietnam during the late 1950s to serve as advisors and assistants to the South Vietnamese military in its fight against the Viet Cong, and the shoes which they wore in the field quickly showed themselves to have serious short-comings. By the early 1960s, it was clear that some serious changes needed to be made to the fighting man’s footwear. Even after American ground troops landed in March 1965, the military kept examining and evaluating uniforms and equipment to make sure that the troops had the optimal gear, and this resulted in the soldiers’ boots undergoing numerous revisions over the duration of the conflict.

Model 1945 Tropical Combat Boot

During the late 1930s and into the early 1940s, American troops were issued short leather boots and canvas gaiters which covered the ankle and extended halfway up the shin. The troops disliked this arrangement for several reasons: the laces on the gaiters would wear out and break, the canvas fabric needed to be replaced due to the constant-wear-and-tear of combat operations, and the large number of laces and eyelets made the leggings a pain to put on and take off. In fact, rather than go through this fussy aggravating task, the soldiers simply never took their boots and leggings off, which would inevitably lead to the men suffering from foot problems (Risch 1953, pages 103-104).

Shortly after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, four infantry platoons were activated and tasked with patrolling the jungles around the Panama Canal, which the United States controlled (and would continue to until 1999). Under Captain Cresson H. Kearny, experiments were carried out in Panama which tested various pieces of military kit for jungle warfare operations, and these experiments concluded that the all-leather service boots which were worn by the men deteriorated quickly in the hot humid jungle climate (Risch 1953, page 109).

In the middle of 1942, the Research and Development Branch of the US Army’s Quartermaster Corps expressed interest in a boot which would replace the standard-issue boot-and-gaiter combination. At the same time, the Desert Training Center had requested a boot that was suited for desert warfare conditions. Meanwhile, in July 1942, Gen. Douglas MacArthur pressured the Quartermaster Corps to invent a new boot which was better suited to jungle warfare (Risch 1953, pages 103-104, 109).

Attempts were made by some soldiers in the field to improve their footwear, but with varying success. For example, the men of the US Army’s 32nd Infantry Division, which saw action in New Guinea against the Japanese, affixed metal hobnails to their leather soles in order to make the soles have better grip and traction. However, over time, these metal studs would wiggle their way out (interestingly, this was also a problem faced by the ancient Roman legionnaires, as hobnails from their caligae sandals are frequently found in Roman military sites). Another problem was that the boots’ all-leather construction quickly deteriorated in the hot humid climate, sometimes in just ten days! The leather rotted and cracked when exposed to perpetual moisture, and the fabric stitching which held the various pieces of the boots together (known as “welt”) snapped and frayed and the boots literally fell apart (Stauffer 1956, page 296).

A new design for a jungle boot was clearly needed. This new boot needed to have its leather sole replaced with a rubber sole, which was more resistant to moisture and could better grip surfaces. Furthermore, this rubber sole needed protruding cleats to provide increased grip and traction, and it all had to be molded as a single piece rather than having a flat sole with the cleats nailed or glued on. Due to the poor survivability of leather, it was decided to substitute some parts of the boot’s construction with canvas. The jungle boot design that the Quartermaster Corps came up with had a corrugated rubber sole and an upper made of cotton duck canvas which reached halfway up the shin, measuring a total of 11.5 inches in height. On August 31, 1942, the Quartermaster Corps finalized its design for a new jungle boot and requested 200,000 pairs. However, a series of problems meant that production would be delayed. The first examples of these boots were issued to men serving in New Guinea and Guadalcanal towards the end of the campaign to take possession of that island. The boot was light and airy and it could be quickly dried out if saturated with moisture, but it was uncomfortable to wear. It provided minimal arch support which resulted in many complaints of sore feet, and the poor fit frequently caused blisters. Additionally, the cotton canvas uppers shrank when wet, and soldiers complained about how the upper edge of the canvas upper would roughly rub against the skin causing stinging red rashes. The men also complained that the cleats on the soles were packed too closely together with only narrow gaps in between them. This allowed mud and dirt to accumulate in these spaces which would be difficult to clean out. Over time, the sediment would get compacted and compressed, and would make the underside of the boot completely smooth and flat, offering no grip or traction at all (Risch 1953, page 109; Stauffer 1956, pages 296-297).

On February 1, 1943, General George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff of the US Army, reported that he had returned from an inspection tour of units serving in North Africa, and he asserted that the boots which were currently worn by troops serving in that theater were unfit for use in the field, being too light and not rugged enough for the hard-wearing wear-and-tear of combat operations. He requested that a new boot be designed and issued to the men. One of the potential designs which the Quartermaster Corps investigated was one worn by Canadian troops which was a heavy-duty boot with a buckled strap near the top. The Quartermaster Corps ordered the Boston Depot to produce samples of this boot for testing, which were then presented to Gen. Marshall on February 5. By July 1943, experimentation was underway, and after field testing yielded positive results, the Quartermaster Corps published a report on November 16, 1943 requesting that this new boot be the standard-issue boot of American combat troops. The request was approved, and in January 1944, mass production of this new combat boot began (Risch 1953, pages 103-104). As good as they were, these new boots had one flaw – they weren’t waterproof. According to a history of the US Army’s Quartermaster Corps published in 1953, “Since leather is a permeable material, no leather boot is waterproof, no matter how carefully designed. The major leaking occurred at the seams and could not be eliminated by the use of dubbing, which furthermore inhibited drying” (Risch 1953, page 106). To solve or at least to mitigate this problem, the Quartermaster Corps advised frequent changing of socks or wearing rubber overshoes (Risch 1953, page 106).

Field Combat Boot, issued to men fighting in Europe. The Model 1945 jungle boot looked similar, except the upper was made of cotton duck canvas instead of leather. Risch, Erna. The Quartermaster Corps: Organization, Supply, and Service, Volume I. Chapter 3 – “The Development of Army Clothing”. Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1953. Page 105.

Regarding the complaints that soldiers in the Pacific Theater had made concerning their jungle boots, the Quartermaster Corps replaced the canvas fabric with nylon. The upper was fastened with a pair of horizontal leather straps and brass buckles. The boot had a leather mid-sole, a full-length cleated rubber outer sole, and a molded cleated rubber heel. Soles were stitched onto the boot’s body, which was made of brown leather. To aid in drainage, a pair of brass eyelets were sunken into the inside arch. The size of the boot was also changed from 11.5 inches to 10.5 inches. By February 1944, the new prototype was ready and was sent out for field testing. After receiving favorable reports, the Quartermaster Corps declared that this was now the new standard-issue jungle boot in November 1944. However, actual production didn’t begin until the summer of 1945, and by that time, battles had shifted northward away from the hot humid tropical jungles to more temperate settings where jungle boots were not needed. Even so, those soldiers who received these new-and-improved jungle boots generally gave them favorable reviews. The war ended a few months later, and all orders for jungle boots were cancelled (Risch 1953, page 110; Stauffer 1956, pages 297-298).

Model 1945 jungle boot. Photograph courtesy of Moore Militaria.

https://www.mooremilitaria.com/combat-boots.html.

https://www.mooremilitaria.com/media/wysiwyg/Okinawa_Boot.jpg.

Model 1945 jungle boot. Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots”. https://www.vietnamgear.com/kit.aspx?kit=217.

During the 1950s and early 1960s, these boots were issued to American military advisors serving in South Vietnam, but these boots soon proved to be inadequate for the task at hand. The leather buckle straps kept getting caught on vegetation, the cotton canvas fabric quickly wore out, and the thread stitching which held the different components together rapidly deteriorated in the humid climate (often in just four or five weeks) to the point where the boots literally fell apart (“Natick Pamphlet Details Vietnam Support”, page 26; Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots”). A better jungle boot was needed.

Leather Combat Boot, 1st Pattern

The all-black all-leather combat boot was the standard-issue footwear for men of the United States military during the 1950s and the first half of the 1960s. These were the boots which were worn by US Army ground troops and US marines in Vietnam until early 1966.

Throughout the 1950s and into the early 1960s, the US military anticipated going to war with the Soviet Union in central Europe. Consequently, many soldiers were sent to Vietnam wearing uniforms which were much better suited to the temperate climate of western Germany rather than the burning hot chronically wet chronically humid conditions of Southeast Asia. In such conditions, the thread stitching which held the sole to the rest of the boot frayed and rotted, often within four to five weeks. The leather boots were heavy and uncomfortable to wear for prolonged periods in the hot humid climate. The leather also deteriorated and cracked from being constantly exposed to moisture. When submerged underwater, they took a long time to dry out, and the ability to retain moisture inside the boot made many soldiers susceptible to trenchfoot. Finally, the relatively flat all-leather sole didn’t provide much traction to men trapsing up and down slippery muddy surfaces.

1st Pattern leather combat boot. Photograph courtesy of Moore Militaria.

https://www.mooremilitaria.com/combat-boots.html.

https://www.mooremilitaria.com/media/wysiwyg/Combat_Boot_Leather2.jpg.

Even after they ceased being used by front-line troops, these leather boots continued to be worn by rear personnel, as numerous photos can attest. Furthermore, aircraft crews were ordered to continue using the all-leather boots instead of the nylon jungle boots which were adopted afterwards because of the danger that the plastic nylon fabric would melt onto their skin in the event of a fire (Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots DMS Spike Protective”).

DMS (direct molded sole) Jungle Boot, 1st Pattern. Also unofficially known as the Model 1960 jungle boot

In January 1960, a new pattern of jungle boot was invented. The cotton duck canvas fabric was changed to nylon plastic, which was able to hold up to more wear-and-tear. The inward side of the shoe had a pair of perforated brass disks which were sunken into the surface of the leather. The cleated rubber sole was the so-called “Vibram pattern”, which had originally been developed for mountain climbing (Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots DMS”). The sponginess of the cushioning absorbed and retained water for prolonged periods of time. To reduce the likelihood of this happening, all forms of cushioning were removed. This wasn’t bad when walking on soft ground, but when you were walking on hard surfaces like concrete, each step was especially jarring – ask me how I know.

The 1st Pattern DMS jungle boot was first issued to the men of the US Army Special Forces, also known as the Green Berets, in August 1960. For a while, this model was used exclusively by the Special Forces while the remainder of US Army troops continued to use the all-leather service boots (Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots DMS”).

The first non-Special Forces unit to receive the 1st Pattern DMS jungle boot was the 3rd Marine Recon Battalion, which was issued the boot in 1963. For six months, the marines put these boots through the ringer at the testing grounds on Okinawa, at Camp Fiji in Japan, and in the thick jungles outside of Subic Bay in the Philippines. At the end of this six-month testing session, the troops of the 3rd Marine Recon Battalion were interviewed on what they thought of this new boot. Only 54% of the men thought that the boot was a good design. Their principal complaint was the addition of a metal insert into the boot to reduce puncture by punji sticks, but this made the boot extremely uncomfortable to wear. However, 93% responded that they thought that the boot was lighter and cooler than the all-leather service boots that they had been wearing up to that point. When asked how the boot could be further improved, the marines responded that the boot needed better ankle support, metal hooks-and-eyes instead of flimsy plastic ones which could easily break, and metal heels and toes. In the end, the marines decided to pass on the 1st Pattern DMS jungle boot (“The Green Suede Boot”. Marine Corps Gazette, volume 47, issue 1 (January 1963). Page 19).

1st Pattern DMS jungle boot. Photograph courtesy of Moore Militaria.

https://www.mooremilitaria.com/combat-boots.html.

https://www.mooremilitaria.com/media/wysiwyg/_First_Pattern_Jungle_Boot.jpg.

1st Pattern DMS jungle boot. Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots DMS”. https://www.vietnamgear.com/kit.aspx?kit=584.

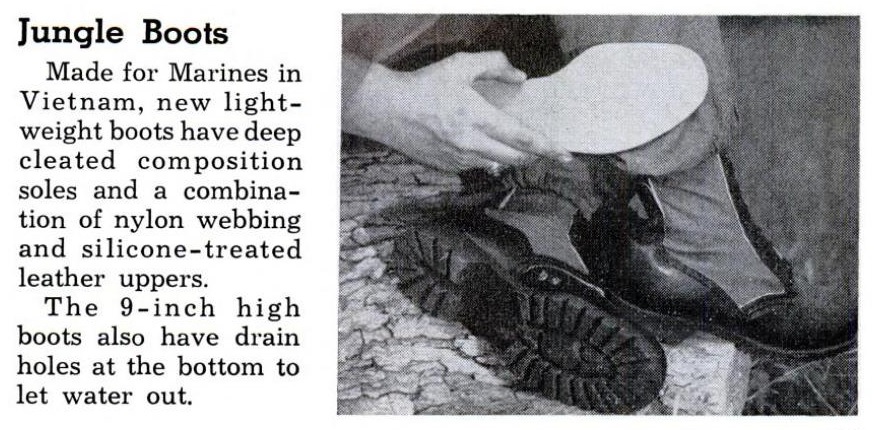

A vignette showing the 1st Pattern DMS jungle boot being adopted by the US Marine Corps. Note the black leather backstrap and the lack of reinforcing ankle straps, which would be seen on the 3rd Pattern. However, contrary to what the paragraph suggests, these boots were not made specifically for the Marines – they were made for the US Army Special Forces first, then afterwards adopted by the rest of the US Army, and after that adopted by the Marines. Popular Mechanics, volume 124, issue 4 (October 1965), page 139.

DMS Jungle Boot, 2nd Pattern. Also unofficially known as the Model 1965 jungle boot

At Fort Benning, Georgia in January 1962, tests were carried out to determine the suitability of a new version of the direct-molded sole (DMS) jungle boot. A gusset was added to the boot to prevent leeches from crawling inside. The tests showed that this design was unsatisfactory and it was rejected (U.S. Government Research Reports, volume 37, issue 9 (May 5, 1962). Page 110). $225,000 were allocated for R&D for creating and testing the new model. Development was carried out jointly by the US Army’s Natick Laboratories and the civilian shoe industry (House of Representatives Committee on Armed Forces 1966, page 8,177). The boots were undergoing R&D testing until April 1965 (“Hearings, Part 3: Operations and Maintenance” 1966, page 789).

The leather upper cuff and backstrap was changed to olive green nylon, just like the rest of the boot’s fabric structure. Also, the shape of the drainage holes was slightly changed so that they would be in-flush with the boot’s surface rather than being recessed into the leather (Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots DMS 2nd Pattern”).

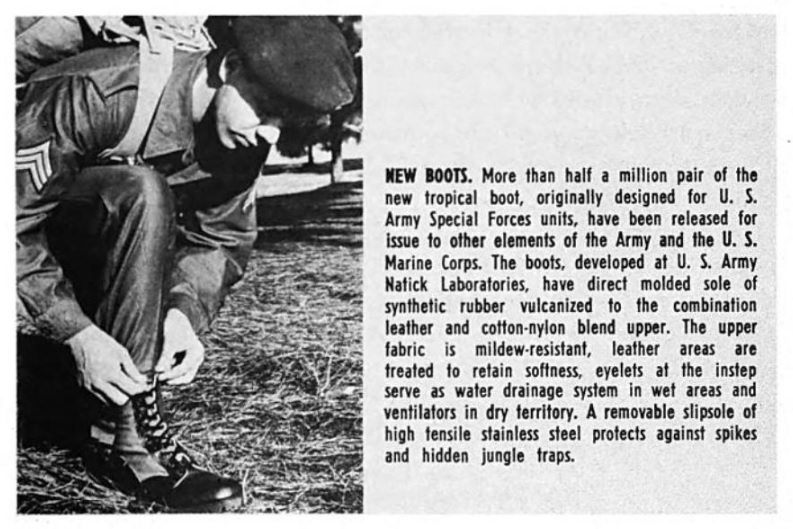

A sergeant of the US Army Special Forces, also known as “the Green Berets”, puts on his 2nd Pattern DMS jungle boots. Image from “ROTC Scholarships”. Army Information Digest, volume 20, issue 11 (November 1965). Page 31.

2nd Pattern DMS jungle boot. Photograph courtesy of Moore Militaria.

https://www.mooremilitaria.com/combat-boots.html.

https://www.mooremilitaria.com/media/wysiwyg/Second_Pattern_Jungle_Boot.jpg.

2nd Pattern DMS jungle boot. Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots DMS 2nd Pattern”. https://www.vietnamgear.com/kit.aspx?kit=138.

In January 1965, the 2nd Pattern DMS jungle boot was declared by the US Army to be its new standard-issue jungle boot (Eustis 1966, page 49). Four shoe companies were tasked with manufacturing these boots for the US military (House of Representatives Committee on Armed Forces 1966, page 8,177). On March 25, 1965, Brigadier-General Melvin D. Henderson, Assistant Chief of Staff for Logistics, Headquarters Office, US Marine Corps, recommended that the Marines (who had just begun combat operations in Vietnam barely three weeks earlier) ought to adopt the new 2nd Pattern DMS jungle boot too (Department of Defense Appropriations for 1966. Part 4: Procurement (1965), page 342). By October 1965, the 2nd Pattern DMS jungle boot was adopted by the US Marine Corps (Popular Mechanics, volume 124, issue 4 (October 1965), page 139).

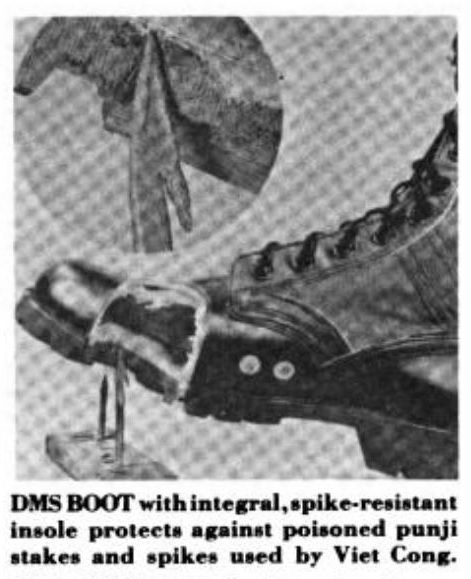

Punji sticks – sharpened pieces of wood or bamboo – were a favored booby trap used by the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese, and they became a big problem for American troops in Vietnam. These spikes were so sharp that they could go right through the thick rubber soles of GI jungle boots. To add insult to injury, the communists often coated these sharpened sticks with feces to cause infection (The Vietnam War, episode 5 – “The Elusive Enemy”). To prevent sharpened spikes from penetrating through the sole and stabbing the foot, an insert of steel sheeting was created to be placed inside the boot (“Hearings, Part 3: Operations and Maintenance” 1966, page 789). However, complaints quickly mounted that slipping a sheet of steel into your shoe, and then putting your foot in, made the shoe extremely uncomfortable to wear and also caused blisters (“Natick Pamphlet Details Vietnam Support”, page 26).

Although the 2nd Pattern DMS jungle boot was adopted by the US Army and the US Marines in 1965, they were issued in very limited numbers at first. In fact, it’s been stated that many soldiers who acquired these boots did so by buying them on the Vietnamese black market rather than waiting for them to be issued. For much of 1965, both soldiers and marines wore the older all-leather black service boots.

By the end of 1965, jungle boots were being adopted with greater frequency amongst the troops in South Vietnam (“Annual Report of the Secretary of Defense: July 1, 1965 to June 30, 1966”, page 34). One report stated “Since their characteristics were particularly well suited to Vietnam and the addition of steel inserts in the boots protects against poisonous spikes planted by the enemy, they are now being furnished for all of our combat forces there” (“Supply Line to Vietnam”, page 37). One report in January 1966 said that Gen. William Westmoreland, the supreme commander of all American military forces in South Vietnam, credited the 2nd Pattern DMS jungle boot as one of the most important pieces of gear to be used by soldiers in Vietnam since the war began (House of Representatives Committee on Armed Forces 1966, page 8,177).

Yet despite being declared the new standard-issue footwear for the US Army and the US Marines, it was proving difficult to supply the number of jungle boots needed for service in Southeast Asia (Subcommittee on Federal Procurement and Regulation of the Joint Economic Committee 1966, pages 104-105). Demand far exceeded supply, and suppliers had a hard time providing the requested number of jungle boots to troops serving in Vietnam according to testimony given on March 9, 1966. For the time being, many soldiers had to just make do with being issued the all-leather service boots instead (“Hearings, Part 3: Operations and Maintenance” 1966, pages 226, 788). A Congressional hearing held on March 23, 1966 reported “All of our requirements in Vietnam are being very well met with respect to all clothing items. In the case of one or two new items such as the jungle boot, we have to use substitutes yet, for a period of time, because the boot is brand new. When I last checked on the figure, we had shipped almost 400,000 pairs of the new combat boot, so we have a great many of them out there. We also use the regular leather in addition…We have experienced some shortages. None of these affect Vietnam itself except the newly developed jungle boot and the recently developed lightweight combat fatigue uniforms, and we are getting substantial deliveries of these and have been for almost a full year. But supply has not quite caught up with demand and we are having to make up the deficits out of the regular items of both combat boots and combat fatigues” (Subcommittee on Federal Procurement and Regulation of the Joint Economic Committee 1966, pages 83, 106).

Robert McNamara, Secretary of Defense, reported in a Senate hearing on April 20, 1966 that “The typical [leather] army boot is not nearly as effective as the new jungle boot which was originally designed for use only by the Special Forces, so we are rushing to equip all men with the new jungle boot” (United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations 1966, page 207). Even so, these new boots weren’t perfect. With the constant wear-and-tear of combat operations, it was said that a pair of jungle boots would last for only six months until they had to be replaced (“Hearings, Part 3: Operations and Maintenance” 1966, page 789).

DMS Jungle Boot, 3rd Pattern. Also unofficially known as the Model 1966 jungle boot

The 3rd Pattern DMS jungle boot, which was designed in February 1966, was a slight improvement on the 2nd Pattern. The most obvious change was the addition of a 2-inch wide diagonal strip of nylon on each side to serve as an ankle reinforcement (Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots DMS Spike Protective”). However, even with this addition, ankle support was still minimal – I can speak from direct personal experience on this. There were many times where I lost my balance while wearing a backpack and wearing jungle boots, and my feet simply buckled inwards. After the second or third time, you become very conscious of your posture, your stride, your footsteps, and the exact orientation of your legs, ankles, and feet to prevent this unpleasant experience from happening again.

In addition to adding the ankle reinforcing strap, the steel shank was shorter in order to reduce breaking of the outsole, and the ventilation holes were placed higher up. The new jungle boot was being tested by the US Army Rangers at Fort Benning, Georgia, at Dahlonega, Florida, and near Elgin Air Force Base, Florida as well as at Fort Clayton’s Tropic Test Center in the Panama Canal Zone (“The Infantry Board”, page 29).

During the Korean War and the Vietnam War, landmines resulted in a large number of foot and leg amputations. This led to Natick Laboratories researching how to make combat boots more blast resistant. The solution was to incorporate an investment-cast stainless steel wedge filled with an aluminum honeycomb into the new model for the jungle boot. (Reed 1966, pages 43-44; “Natick Pamphlet Details Vietnam Support”, page 26). A less obvious addition was adding a thin steel plate inside the sole of the boot to guard against punji sticks. Earlier, a separate steel plate could be slipped into the shoe, but the 3rd Pattern DMS jungle boot had a steel plate incorporated directly into the boot’s sole (“Natick Pamphlet Details Vietnam Support”, page 26).

3rd Pattern DMS boot. Photograph courtesy of Moore Militaria.

https://www.mooremilitaria.com/combat-boots.html.

https://www.mooremilitaria.com/media/wysiwyg/Third_Pattern_Jungle_Boot_Vibram_Sole_2.jpg.

A cut-away photo showing the integral steel plate inside the rubber sole of the 3rd Pattern DMS jungle boot. Image from “Natick Pamphlet Details Vietnam Support”. Army Research and Development News Magazine, volume 8, issue 9 (October 1967). Page 26.

The 3rd Pattern DMS boot was officially adopted by the US military in May 1966 (Imperial War Museums. “Boots, Combat, Tropical, DMS (3rd Pattern): US Army”).

In the second half of 1966, all Special Forces personnel, front-line combat troops, and military advisers were issued two pairs of jungle boots. In November 1966, jungle boots began to be issued to all rear military personnel, which were to replace the older all-leather service boots. In December 1966 and January 1967, a total of 340,980 pairs of jungle boots were shipped to South Vietnam (Preparedness Investigating Subcommittee 1967, page 15).

Even so, some troops had a hard time getting these boots sent to them, including the marines. This was because the boots were shipped to the US Army first and the US Marine Corps afterwards. On March 2, 1967, General Wallace M. Greene Jr., Commandant of the United States Marine Corps, testified before the Senate that Marines stationed in South Vietnam were not getting the sufficient number of jungle boots that they requested: “There had been developed a new combat boot which had a metal liner in the bottom which would protect your foot from the punji stick, if you fell into a punji trap…We asked to get this new boot and the production was accelerated” (“Worldwide Military Commitments” 1967, page 264). By January 1, 1967, the Marines in I Corps had 214,500 pairs of these boots, out of a desired inventory of 410,200 pairs, and acquiring them proved to be slow. It was estimated that the total allotment of jungle boots for the US marines in South Vietnam wouldn’t be fulfilled until July 1, 1968 (“Worldwide Military Commitments” 1967, page 265).

Leather Combat Boot, 2nd Pattern (DMS)

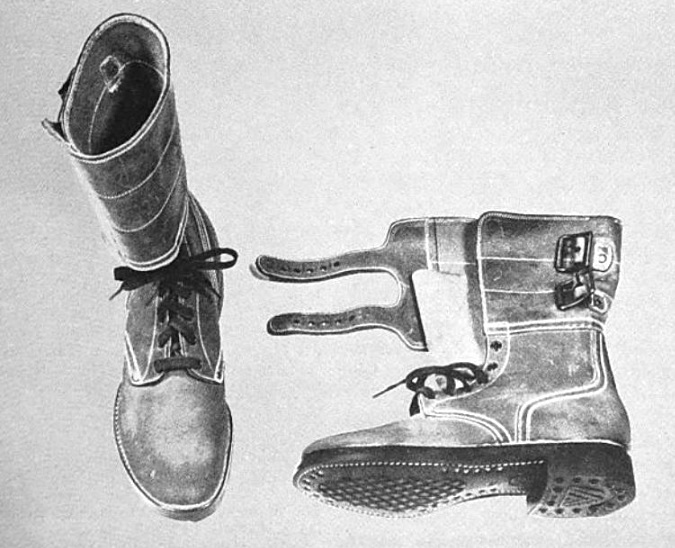

Even after fabric-and-leather jungle boots were adopted by ground troops, many military personnel in Vietnam continued to be issued the all-leather service boot. However, an updated version was developed which attempted to correct some of the problems with the earlier 1st Pattern version. The major change was replacing the stitched leather sole with a directly-molded rubber sole featuring a zig-zag cleat pattern, known as a “ripple pattern sole”. This sole had superior grip and lasted longer than the leather-soled 1st Pattern leather boots. They also weighed 6 ounces less than the all-leather boots (Vietnam Gear. “Leather Combat Boots DMS”).

“The new standard combat boot, complete with DMS, built-in spike shield and a combination of hooks and eyes (a Marine exclusive for fast donning and doffing) will be phased into supply systems as sizes of the old boot run out. The new boot is black, is 1 1/2″ lower than the current boot, comes in half sizes through 14, but in three widths only: narrow, medium, and wide. If your foot is average size (9D) you should be wearing the new boot within two years. Bigger feet may don it sooner” (“The Green Suede Boot”. Marine Corps Gazette, volume 47, issue 1 (January 1963). Page 19).

2nd Pattern leather combat boot (DMS). Photograph courtesy of Moore Militaria.

https://www.mooremilitaria.com/combat-boots.html.

https://www.mooremilitaria.com/media/wysiwyg/Combat_Boot_Leather3.jpg.

In May 1966, the US Marine Corps published their evaluation of the new DMS leather boots, which read as follows: “Tests and evaluation of the Direct Molded Sole (DMS) Boot were conducted to determine suitability for the Marine Corps use. Results of the testing showed the DMS Boot to be superior to the Standard combat boot relative to comfort, maintenance and troop preference and suitability for Marine Corps use. It is recommended that the DMS Boot be adopted for use as a replacement for the current standard combat boot” (Ronco 1967, page 518).

The 2nd Pattern leather combat boot was officially adopted by the US Army on January 5, 1967. It was principally used by aircraft crews, vehicle crews, and rear personnel (“Natick Pamphlet Details Vietnam Support”, page 26; Vietnam Gear. “Leather Combat Boots DMS”).

DMS Jungle Boot, 4th Pattern. Also unofficially known as the Model 1968 jungle boot

The 4th Pattern DMS jungle boot is the boot that’s most often associated with American troops serving in the Vietnam War because it was the one which saw the longest length of service, beginning in 1968 and continuing up to the end of America’s involvement in Southeast Asia in 1975.

The “Panama sole” had been invented in 1944 by Sgt. Raymond Dobie, but it was not subjected to official testing by the military until 1967 when forty pairs of boots were sent to be tested at the Tropic Test Centers in the Panama Canal Zone (Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots DMS Spike Protective Panama Sole”).

In early 1968, the first batch of 4th Pattern DMS jungle boots was sent to the US Army’s 9th Infantry Division serving in the Mekong Delta to undergo field testing. The soldiers of the 9th loved this new version. They liked how the Panama-pattern rubber sole was able to grip onto surfaces a lot better than the older Vibram-pattern sole, and they also liked how the newer soles were a lot easier to clean and didn’t get clogged up full of dirt and mud. The word was passed to the Pentagon – the troops like the new boots (Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots DMS Spike Protective Panama Sole”).

On April 9, 1968, Army Material Command directed that the 4th Pattern DMS jungle boot was to be the standard-issue jungle boot for all combat troops serving in Southeast Asia (Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots DMS Spike Protective Panama Sole”). This would be the jungle boot worn by all US Army ground troops and US marines in Vietnam from 1968 until the end of American involvement in 1973. However, examples of the earlier 3rd Pattern jungle boots continued to be used by some troops until they were phased out of service by 1969.

4th Pattern DMS jungle boot showing the “Panama-pattern” sole, which is still used on jungle boots today. Photograph courtesy of Moore Militaria.

https://www.mooremilitaria.com/combat-boots.html.

DMS Jungle Boot, 5th Pattern. Also unofficially known as the Model 1970 jungle boot

In July 1969, Lieutenant-General George I. Forsythe, Commandant of the Infantry School, requested that the Infantry School’s assistant commandant, the commanding officer of the Combat Development Command Infantry Agency, and the president of the US Infantry Board to examine the gear which was currently used by American military forces in Southeast Asia and to recommend improvements. This body concluded that the pieces of equipment which needed improvement were footwear, individual load equipment, tropical uniforms, helmets, and body armor – so, basically everything. These people agreed that the people who were most qualified to assess the equipment and make recommendations for improvement were the infantrymen themselves. Therefore, a board was set up consisting of senior and junior NCOs who were well-experienced in infantry operations. This board was tasked with examining the five categories mentioned and forwarding their findings and recommendations (Fraser 1969, page 27). Concerning the subject of jungle boots, “The board suggested retention of the tropical combat boot issued for Vietnam with added protection in the soles and sides of the boot… The board suggested that a zipper replace the boot laces, with laces as a backup closure system. The zipper would provide an easier means of putting the boot on and taking it off” (Fraser 1969, page 28). Being able to quickly take boots off would help to mitigate the risks of trenchfoot.

The 5th Pattern DMS jungle boot was adopted by the US Army in March 1970 (Allen 1977, pages 81-82). It was issued predominantly to US Army Special Forces and to troops operating in flood-prone areas like the Mekong Delta. However, these boots gradually found their way to other areas-of-operation (Vietnam Gear. “Tropical Combat Boot Lace-in Zipper”).

5th Pattern DMS jungle boot. Note that it has the earlier Vibram-pattern sole instead of the Panama-pattern sole. Vietnam Gear. “Tropical Combat Boot Lace-in Zipper”. https://www.vietnamgear.com/kit.aspx?kit=662.

In 1971, a UH-1 Huey is ready to lift a downed OH-6 Cayuse helicopter. The man in front is wearing 5th Pattern DMS jungle boots, which had a zipper instead of laces. Notice that he has rigged a grenade ring onto the zipper to make it easier to grab onto. Image from Daugherty, Leo J.; Mattson, Gregory Louis. Nam: A Photographic History. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2001. Page 477.

Yet by that time, America’s military commitment to the war in Southeast Asia was on the wane. The previous year on June 8, 1969, Pres. Richard Nixon attended a conference with Pres. Nguyen Van Thieu of South Vietnam on Midway Island, and Nixon announced that American troops would be gradually withdrawn from South Vietnam as part of the new “Vietnamization” policy. The idea behind “Vietnamization” was that South Vietnamese troops would gradually take over the lion’s share of the fighting as the American troops were pulled out piece-by-piece. Nixon promised that 25,000 American troops would be pulled out of South Vietnam by the end of August 1969 (“Vietnamization”). The first to go were the 814 men of the 3rd Battalion of the 60th Infantry Regiment of the US Army’s 9th Infantry Division, which departed Saigon on July 8, 1969 aboard nine C-141 Starlifter cargo-transport planes and landed at McChord Air Force Base near Tacoma, Washington (“This Day In History: July 8, 1969 – First U.S. troops withdrawn from South Vietnam”; “Soldiers returning from Vietnam are welcomed with parade, barbecue in Seattle on July 10, 1969”).

However, just because American troops were departing South Vietnam for good, that didn’t mean that the fighting was winding down. Battles were still being waged up and down the length and breadth of the country, and there was no sign of the fighting letting up. More sobering than that, just because American troops were being removed from South Vietnam, that didn’t necessarily mean that Americans would stop being sent overseas to fight and die. Despite President Nixon’s public promise that he would reduce America’s military presence in South Vietnam and bring the troops back home, young men were still being drafted and they were still being forced into military service and they were still being sent overseas to do their tours-of-duty in Vietnam where they would fight and possibly die in a war that the majority of the American public considered all but over. On top of that, Nixon dramatically expanded the war. In 1969, Nixon gave orders to secretly bomb communist locations within neutral Cambodia under the code-name “Operation Menu”. The year afterwards, American and South Vietnamese troops penetrated into Cambodia, but advanced only 19 miles before being ordered to halt. In 1971, American and South Vietnamese troops carried out an operation into Laos. By this point, most Americans both in and out of uniform were sick and tired of this war where there seemed to be no end in sight.

On March 29, 1973, the last remaining American combat troops which were still left in South Vietnam departed the country and went back to the United States. Two years later on April 30, 1975, the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the communists, and the Vietnam War officially came to an end.

The Vietnam War resulted in many hard-learned lessons for the American military, some more obvious than others. Many of those lessons were taught under the brutal and unforgiving tutor of warfare in the hot humid tropics. Drain out and dry out your jungle boots at every opportunity, air your boots out to prevent mold or fungus, keep an extra pair of dry socks in your pack (two pairs if you’ve got them), change your socks regularly, and try to keep your feet dry as much as possible. After all, an infantryman is only as good as his rifle and his feet.

Bibliography

Books

Allen, Lieutenant Colonel Alfred M. Internal Medicine in Vietnam, Volume 1: Skin Diseases in Vietnam, 1965-72. Washington, DC: United States Army, 1977.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Skin_Diseases_in_Vietnam_1965_72/bclsAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Risch, Erna. The Quartermaster Corps: Organization, Supply, and Service, Volume I. Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1953.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Quartermaster_Corps/gsFGpcp71pEC?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Ronco, Paul G. Human Factors and Engineering, Bibliographic Series, Volume 4 – 1966 Literature. Aberdeen: U.S. Army Human Engineering Laboratories, 1967.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Human_Factors_Engineering_Bibliographic/7S4nAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Stauffer, Alvin P. The Quartermaster Corps: Operations in the War against Japan. Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1956.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Quartermaster_Corps_Operations_in_th/CotQAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Articles

Eustis, Major Thomas B. (1966). “To the End of the Line”. Army Digest, volume 21, issue 6 (June 1966). Pages 48-50.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Army_Information_Digest/0QvjQgqOCrwC?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Fraser, Colonel Bruce H. (1969). “Burrs Under the Saddle”. Infantry, volume 59, issue 6 (November-December 1969). Pages 26-29.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Infantry/CO1FJO3F8G0C?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Johnston, Colonel Walter F. (1969). “The Infantry Board”. Infantry (May-June 1969), pages 28-30.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Infantry/CO1FJO3F8G0C?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=jungle+boot&pg=RA2-PA29&printsec=frontcover.

Reed, N. L. (1966). “New Materials for the Modern Army”. Army Digest, volume 21, issue 10 (October 1966). Pages 42-45.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Army_Information_Digest/0QvjQgqOCrwC?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Department of Defense Annual Report for Fiscal Year 1966. “Annual Report of the Secretary of Defense: July 1, 1965 to June 30, 1966”. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1967. Pages 1-67.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Annual_Report_for_Fiscal_Year_Including/Xxz0AAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Department of Defense Appropriations for 1966. Part 4: Procurement. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1965.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Department_of_Defense_Appropriations_for/wXxRAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations House of Representatives. Part 3: Operations and Maintenance. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1966.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Operation_and_maintenance_Monday_March_7/MAREAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

House of Representatives Committee on Armed Forces (1966). “Hearings on Fiscal Year 1967 Defense Research, Development, Test and Evaluation Program” (January 24, 1966). Pages 8,167-8,215.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Hearings_Before_and_Special_Reports_Made/DunR65Cph6YC?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Popular Mechanics, volume 124, issue 4 (October 1965), page 139.

https://books.google.com/books?id=X-MDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA139&dq=Vietnam+jungle+boot+marines+Popular+Mechanics+October+1965&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjD54Hl3-SMAxWzGFkFHZaTKkoQ6AF6BAgGEAM#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Preparedness Investigating Committee, Committee on Armed Forces, United States Senate (1967). “Investigation of the Preparedness Program”. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1967.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_U_S_Army_in_Vietnam/R4Itmsetq_MC?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Preparedness Investigating Committee, Committee on Armed Forces, United States Senate (1967). “Worldwide Military Commitments” (March 2, 1967). Pages 239-276.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Worldwide_Military_Commitments_Hearings/CAZvLqiLcnMC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Vietnam+tropical+combat+boot&pg=PA264&printsec=frontcover.

Subcommittee on Federal Procurement and Regulation of the Joint Economic Committee (1966). “Economic Impact of Federal Procurement” (March 23, 1966). Pages 65-141.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Hearings_Reports_and_Prints_of_the_Joint/0Cc4AAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations (April 20, 1966). Pages 159-227.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Hearings_Reports_and_Prints_of_the_Senat/Rpk3AAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

U.S. Government Research Reports, volume 37, issue 9 (May 5, 1962). Page 110.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/U_S_Government_Research_Reports/No2jaBICn5kC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=panama+sole+boot&pg=RA1-PA111&printsec=frontcover.

“Natick Pamphlet Details Vietnam Support”. Army Research and Development News Magazine, volume 8, issue 9 (October 1967). Page 26.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Army_Research_and_Development/tCPcAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

“ROTC Scholarships”. Army Information Digest, volume 20, issue 11 (November 1965). Pages 29-31.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Army_Information_Digest/b5Dy7vrVW0MC?hl=en&gbpv=1.

“Supply Line to Vietnam”. Department of Defense Cost Reduction Journal, volume 3, issue 2 (Spring 1967). Pages 36-38.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Defense_Management_Journal/d3j7TX9iA98C?hl=en&gbpv=1.

“The Green Suede Boot”. Marine Corps Gazette, volume 47, issue 1 (January 1963). Page 19.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Marine_Corps_Gazette/lhtoylXTfS0C?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Websites

History. “This Day In History: July 8, 1969 – First U.S. troops withdrawn from South Vietnam”.

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/july-8/first-u-s-troops-withdrawn-from-south-vietnam.

History Link. “Soldiers returning from Vietnam are welcomed with parade, barbecue in Seattle on July 10, 1969”, by Cassandra Tate (September 23, 2012).

https://www.historylink.org/File/10184.

Imperial War Museums. “Boots, Combat, Tropical, DMS (3rd Pattern): US Army”.

https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30110276.

The Miller Center. “Vietnamization”.

https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/educational-resources/vietnamization.

Moore Militaria. “Tropical Combat Boots”.

https://www.mooremilitaria.com/combat-boots.html.

Vietnam Gear. “Leather Combat Boots”.

https://www.vietnamgear.com/kit.aspx?kit=75.

Vietnam Gear. “Leather Combat Boots DMS”.

https://www.vietnamgear.com/kit.aspx?kit=76.

Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots”.

https://www.vietnamgear.com/kit.aspx?kit=217.

Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots DMS”.

https://www.vietnamgear.com/kit.aspx?kit=584.

Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots DMS 2nd Pattern”.

https://www.vietnamgear.com/kit.aspx?kit=138.

Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots DMS Spike Protective”.

https://www.vietnamgear.com/kit.aspx?kit=136.

Vietnam Gear. “Jungle Boots DMS Spike Protective Panama Sole”.

https://www.vietnamgear.com/kit.aspx?kit=137.

Vietnam Gear. “Tropical Combat Boot Lace-in Zipper”.

https://www.vietnamgear.com/kit.aspx?kit=662.

Videos

The Vietnam War. Episode 5 – “The Elusive Enemy”. Hosted by Walter Cronkite. CBS, 1985.

https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x8o84z0.

Categories: History, Uncategorized

This was so interesting! Thanks for posting!