Introduction

Thanks to the 2002 movie Windtalkers starring Adam Beach and Nicolas Cage, many people have become aware of the Navajo code-talkers who served with the US Marines in the Pacific Theater against the Japanese during World War II. Numerous books have been written about these men, which certainly helps to raise historical awareness, but it also gives the impression that the Navajo were the only Native American personnel serving in the American armed forces in WWII using their native language to elude enemy spies and code-breakers. However, this is not true – the Navajo were not the only code-talkers serving in the US military, nor were they the first to use their language as a weapon in the war effort.

The US Army, fighting in Europe against the Nazis, used their own Native American code-talkers to communicate orders and information to different Allied units. These men were not Navajos but Comanches from Oklahoma, assigned to the US Army’s 4th Infantry Division, who fought their way through northern France and into Germany in 1944 and 1945.

The First Code-Talkers

The first Native American “code-talkers” served in the US Army during the First World War. These were Choctaw Indians who served with the US Army’s 36th Infantry Division on the Western Front. During the closing months of the war, men from other Native American tribes also served as code-talkers, including Cherokees, Osages, Comanches, and Cheyennes (1).

Private Tobias Frazier, a Choctaw Indian code-talker who served with the US Army’s 36th Infantry Division on the Western Front during World War I. Photo 22190, from the Photograph Collection of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Training

In 1940, with the situation in Europe and the Pacific becoming increasingly violent, the United States realized that it would likely get sucked into the fighting sooner or later, despite the prevailing isolationist sentiment at that time. Tanks, ships, and aircraft began to be produced with much greater urgency, and tens of thousands of men were trained for combat in a war that they hoped they wouldn’t have to take part in. They remembered what happened the last time that America went to war – 53,402 “doughboys” were killed-in-action on the Western Front in 1917 and 1918 – and this new “blitzkrieg” war seemed to be far worse (2).

However, the United States was still technically neutral – it wouldn’t get officially involved in WWII until the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, but that would be over a year into the future. Even so, President Franklin D. Roosevelt saw that the writing was on the wall – war was coming, and the US had better prepare for it now. In September 1940, Pres. Roosevelt signed the “Selective Service and Training Act”. This was a law which would allow US citizens to be drafted into the military during peacetime; previously, drafts had only occurred after hostilities had already begun. It was a way to quickly increase the size of the US Army prior to the United States’ inevitable involvement overseas (3).

One problem that the military anticipated was the enemy intercepting radio or telegraph messages. Remembering that the employment of Native American code-talkers had worked in WWI, the military decided to do it again. However, finding a particular language to use was problematic. During the 1800s and even into the late 1930s, German scholars, most of them being anthropologists and linguists, had visited the United States and had extensively studied many of the Native American tribes, describing their appearance, customs, religious beliefs, and languages. Yet, one of the tribes which these German academics had relatively ignored were the most powerful tribe of the American southwest – the Comanche. In fact, the Germans knew hardly anything about them (4).

In the 1930s, the Germans began to pay more attention to the Comanche, probably due to them realizing that they had very little information about these people. In 1932, the German anthropologist Gunther Wagner did a study of the Comanche people. In 1939, a group of Germans claiming to be students came to the Comanche territory. The FBI believed that these people (who were too old to be students) were actually spies and arrested all of them on a charge of espionage (5).

The US Army decided that it was going to employ Comanches as code-talkers, while the US Marine Corps decided to use Navajos. While there were already several Comanche men serving in the military, the upper brass decided that it would be better to find fresh recruits for this job rather than go through the effort of re-training soldiers who were already in uniform. Consequently, in December 1940 and January 1941, the US Army recruited a total of seventeen Comanche men from the Comanche reservation in western Oklahoma to serve as code-talkers. These men were (6):

- Charles Chibitty

- Haddon Codynah

- Robert Holder

- Forrest Kassanavoid

- Wellington Mihecoby

- Perry Noyabad

- Clifford Otitivo

- Simmons Parker

- Melvin Permansu

- Elgin Red Elk

- Roderick Red Elk

- Albert Nahquaddy Jr.

- Larry Saupitty

- Morris Tabbyetchy

- Anthony Tabbytite

- Ralph Wahnee

- Willie Yacheschi

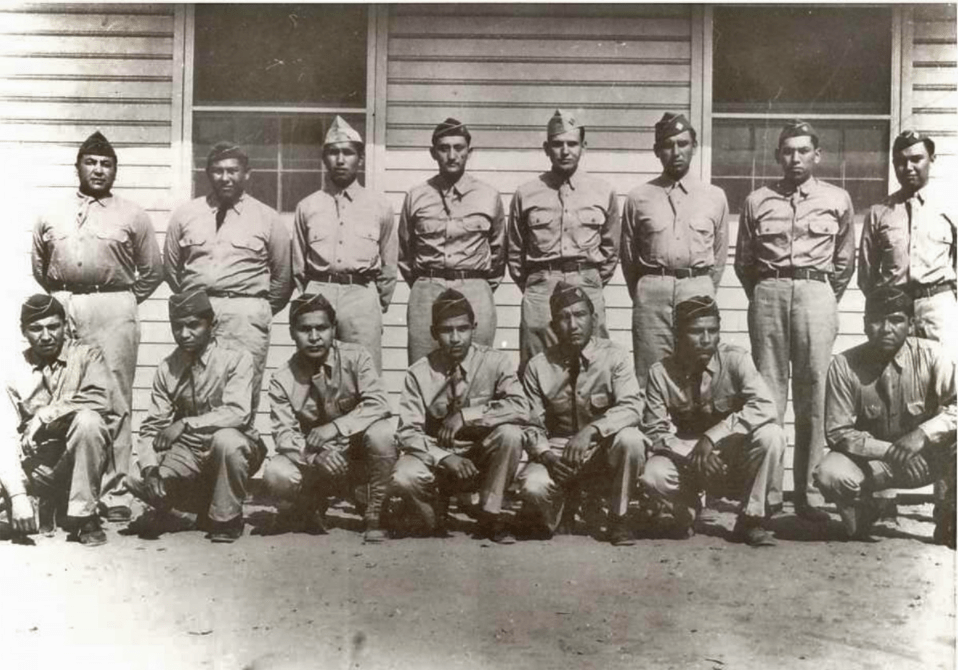

These men were assigned to the 4th Signal Company, 4th Infantry Division, US Army, and were put under the direction of Lieutenant Hugh F. Foster. The preliminary stages of the training took place at Fort Benning, Georgia where they were trained in basic military duties as well as in radio and telephone operations, Morse code, and semaphore flag signaling. Approximately 250 code-terms needed to be memorized. They completed their language and communication training on October 30, 1941, and afterwards were dispatched to Louisiana to carry out field exercises (7).

The Comanche code-talkers of the 4th Signal Company, 4th Infantry Division. Photograph taken at Fort Benning, Georgia during their training. US Army. “Comanche language helped win World War II”, by Cindy McIntyre. https://www.army.mil/article/178195/comanche_language_helped_win_world_war_ii. Accessed on March 19, 2022.

In January 1944, the 4th Infantry Division set sail for England in preparation of the Allied invasion of France. For the next four months, the men underwent even more rigorous training to prepare them as much as possible for breaking through “the Atlantic Wall” and waging war across Nazi-occupied Europe (8).

Of these seventeen original recruits, three were discharged after training at Fort Benning, and one was transferred to a different unit just a few days before the D-Day invasion, leaving thirteen left to serve in the 4th Signal Company (9).

Combat in the European Theater

On June 6, 1944, “D-Day”, the thirteen Comanche code-talkers landed in Normandy at Utah Beach. Brigadier-General Theodore Roosevelt Jr., the son of the former president and the deputy commander of the 4th Infantry Division, hit the beaches along with his men. By his side was one of the Comanche code-talkers, PFC Larry Saupitty, who not only served as the general’s radioman but also his orderly and chauffeur. The 4th Infantry Division had mistakenly landed in the wrong place on the beach, landing several thousand yards away from where they were supposed to land. General Roosevelt needed to inform the other troops who were still waiting on board the transport ships, and since he didn’t want the Germans to intercept the message, he had Saupitty transmit it in Comanche code. It was he who sent the first encoded message in the Comanche language – “We made a good landing. We landed at the wrong place” (10).

Soldiers of the 4th Infantry Division land on Utah Beach during the D-Day invasion of June 6, 1944.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:US_4th_ID_landing_in_Utah_Beach.jpg.

The Comanche code-talkers of the 4th Infantry Division saw action in some of the toughest battles in the European Theater of Operations: D-Day, Cherbourg, St. Lo, the liberation of Paris, the Hurtgen Forest, and the Battle of the Bulge (11).

Calling the Comanches who served in the 4th Signal Company “code-talkers” is slightly inaccurate because this designation creates the impression that this was the only job that these men did. While it’s true that part of their job was to create and relay encoded messages, the majority of their work consisted of laying, repairing, and retrieving communication wire, often while under enemy fire (12).

Although several of the US Army’s Comanche code-talkers were wounded-in-action, none of them were killed. The Germans were never able to break the Comanche code (13).

Post-Script

Throughout the course of World War II, approximately 44,000 Native Americans served in the American military (14). Not just code-talkers, either. It also must be stated that there were other Native Americans who served both in Europe and the Pacific, who belonged to tribes other than the Navajo and the Comanche, who used their languages to communicate encoded messages to one another (15):

- Four Choctaws – Forrester Baker, Schlicht Billy, Andrew Perry, and Davis Pickens – who served in Company K, 180th Infantry Regiment, 45th Infantry Division.

- Three Kiowas – Leonard Cozad, James Paddlety, and John Tsatoke – who served in the 689th Field Artillery Battalion.

- Two Pawnees – Henry Stoneroads and Enoch Jim – who fought in the Philippines.

- Edmund Harjo (Seminole) and Leslie Richards (Muscogee Creek), who served in the Aleutian Islands campaign against the Japanese.

Charles Chibitty, the last surviving Comanche code-talker of World War II, died on July 20, 2005.

Source citations

- Robert Daily, The Code Talkers: American Indians in World War II. New York: F. Watts, 1995. Page 13; Oklahoma Historical Society. “Code Talkers”, by William C. Meadows.

- Oklahoma Historical Society. “Code Talkers”, by William C. Meadows.

- Tom Holm, Code Talkers and Warriors: Native Americans and World War II. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2007. Page 31.

- Tom Holm, Code Talkers and Warriors: Native Americans and World War II. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2007. Page 110; Oklahoma Historical Society. “Code Talkers”, by William C. Meadows.

- Tom Holm, Code Talkers and Warriors: Native Americans and World War II. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2007. Pages 110-111; Oklahoma Historical Society. “Code Talkers”, by William C. Meadows.

- Tom Holm, Code Talkers and Warriors: Native Americans and World War II. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2007. Page 110; Oklahoma Historical Society. “Code Talkers”, by William C. Meadows; Comanche National Museum and Cultural Center. “Comanche Code Talkers”.

- Robert Daily, The Code Talkers: American Indians in World War II. New York: F. Watts, 1995. Page 50; Tom Holm, Code Talkers and Warriors: Native Americans and World War II. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2007. Pages 111, 114-115; Oklahoma Historical Society. “Code Talkers”, by William C. Meadows.

- Tom Holm, Code Talkers and Warriors: Native Americans and World War II. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2007. Page 115.

- US Army. “Comanche language helped win World War II”, by Cindy McIntyre.

- Tom Holm, Code Talkers and Warriors: Native Americans and World War II. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2007. Pages 115-118; US Army. “Comanche language helped win World War II”, by Cindy McIntyre.

- Robert Daily, The Code Talkers: American Indians in World War II. New York: F. Watts, 1995. Page 52; Tom Holm, Code Talkers and Warriors: Native Americans and World War II. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2007. Pages 101-106, 118; Oklahoma Historical Society. “Code Talkers”, by William C. Meadows.

- Tom Holm, Code Talkers and Warriors: Native Americans and World War II. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2007. Page 118; US Army. “Comanche language helped win World War II”, by Cindy McIntyre.

- Oklahoma Historical Society. “Code Talkers”, by William C. Meadows.

- Tom Holm, Code Talkers and Warriors: Native Americans and World War II. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2007. Page 30.

- Oklahoma Historical Society. “Code Talkers”, by William C. Meadows.

Bibliography

Daily, Robert. The Code Talkers: American Indians in World War II. New York: F. Watts, 1995.

Holm, Tom. Code Talkers and Warriors: Native Americans and World War II. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2007.

Comanche National Museum and Cultural Center. “Comanche Code Talkers”. http://www.comanchemuseum.com/code_talkers.html. Accessed on April 7, 2022.

Interviews with German Anthropologists. “Short Portrait: Günter Wagner”. http://www.germananthropology.com/short-portrait/gnter-wagner/288. Accessed on April 7, 2022.

Oklahoma Historical Society. “Code Talkers”, by William C. Meadows. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=CO013#:~:text=In%20December%201940%20the%20army,Albert%20Nahquaddy%20Jr.%2C%20Larry%20Saupitty. Accessed on March 19, 2022.

US Army. “Comanche language helped win World War II”, by Cindy McIntyre. https://www.army.mil/article/178195/comanche_language_helped_win_world_war_ii. Accessed on March 19, 2022.

Categories: History, Uncategorized

Leave a comment