Introduction

Cimoliopterus was pterosaur with a supposed wingspan of 16 feet or thereabouts, which inhabited Europe and North America during the middle of the Cretaceous Period approximately 100-94 million years ago. There are presently two species of this pterosaur genus: Cimoliopterus cuvieri of southern England, and Cimoliopterus dunni of northern Texas. Fragmentary remains found elsewhere in North America might also belong to the latter species.

The European Species

The first specimen of this animal was discovered in 1851 within the Burham Chalk Pit (also called the Lower Culand Pit), located approximately 4.6 miles north-by-northwest of the town of Maidstone, Kent, England (Bowerbank 1851, page 2; Owen 1859, page 100; Owen 1884, page 244; Myers 2015, page 1) (note that Jukes-Brown and Hill state that the fossil was actually found at the village of Newtimber, located in the far eastern part of West Sussex, England (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, page 70), but this can be discounted). The rock layers at the Burham Chalk Pit belong to the Chalk Formation of southeast England, and more specifically, to the Grey Chalk Member which is the lowest/oldest geological unit of the Chalk Formation (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, pages 3-6, 9). The Grey Chalk Member, which dates to the Cenomanian Stage of the middle Cretaceous and spans 100-94 MYA (Myers 2015, page 1), is further sub-divided into “zones” based upon which particular species of invertebrate is most commonly found within a particular layer: the lower Ammonites varians zone, and the upper Holaster subglobulosus zone (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, pages 17-23). Cimoliopterus cuvieri was found within the Ammonites varians zone (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, page 70), which dates to approximately 100-97 MYA. This zone is further sub-divided into five different stratigraphic layers called “beds” (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, pages 36-40). Unfortunately, it wasn’t recorded from which particular bed within the Ammonites varians zone of the Grey Chalk Member that the specimen of this pterosaur was recovered from.

In the year 1851, within the Burham Chalk Pit, the front end of an upper jaw was discovered. This specimen was largely toothless, despite the presence of multiple tooth sockets, except for a single tooth protruding from the front right. This jaw fragment was determined to belong to a pterosaur, and in 1851, James Scott Bowerbank named this fossil Pterodactylus cuvieri (Bowerbank 1851, pages 1-7).

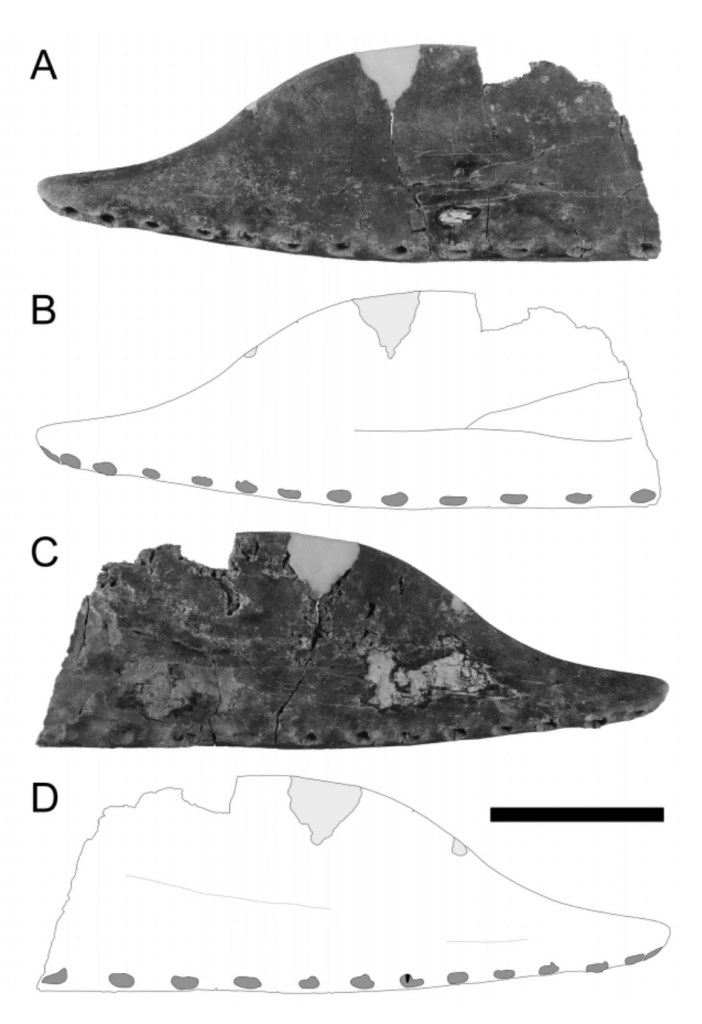

The front of the upper jaw of Cimoliopterus cuvieri. Scale bar = 1 cm. Rodrigues, Taissa; Kellner, Alexander Wilhelm Armin (2013). “Taxonomic review of the Ornithocheirus complex (Pterosauria) from the Cretaceous of England”. Zookeys, volume 308 (June 12, 2013).

Because this animal is known only from partial remains, its exact placement upon the pterosaur tree has been shuffled around hither and thither since its discovery. In 1870, Harry Seeley re-classified it as a species of Ornithocheirus (Seeley 1870, page 113). The ornithocheiraeans were medium-to-large pterosaurs with wingspans ranging 10-25 feet in width (and some paleontologists have asserted that they could grow even larger), making them some of the largest animals that ever flew. Many ornithocheiraeans such as the South American genera Tropeognathus and Anhanguera were distinctive for having large crests on the ends of their jaws. The ornithocheiraeans dominated the world’s skies during the early and middle Cretaceous Period until they were supplanted by another pterosaur group during the late Cretaceous called the azhdarchids, which includes genera such as Hatzegopterus and Quetzalcoatlus, both of which were far larger than the largest ornithocheiraean.

The jawbone’s identity as Ornithocheirus stuck around until 2001, when it was re-classified by David M. Unwin as a species of the Brazilian pterosaur Anhanguera (Unwin 2001, pages 189, 192-193). Then in 2013, Timothy Myers determined that this jawbone didn’t belong to either aforementioned genus, and therefore should be given its own unique name. Consequently, it was re-named yet again to Cimoliopterus, which means “chalk wing” in ancient Greek in reference to its discovery within the Chalk Formation. Myers classified Cimoliopterus as a basal member of the pterosaur super-family Pteranodontoidea, within which is the clade Ornithocheirae, which in turn is split into the families Anhangueridae and Ornithocheiridae (Myers 2015, pages 1-9).

In 2019, another study stated that Cimoliopterus was so distinct from both the anhanguerids and ornithocheirids that it warranted placement within its own family, Cimoliopteridae, along with the species Aetodactylus halli and Camposipterus nasutus (Pêgas et al 2019, page 8). The establishment of the family Cimoliopteridae, and Cimoliopterus‘ placement within it, were restated in a 2022 study of anhanguerid pterosaurs (Duque et al 2022: e2116984).

In 1851, James S. Bowerbank hypothesized that Cimoliopterus cuvieri had a wingspan of 16.5 feet, based entirely on extrapolation of the size of the tooth sockets compared with those of other more well-known pterosaur species. However, even he admitted that this estimate needed to be taken with caution (Bowerbank 1851, page 5). In 2001, David M. Unwin stated that the wingspan was more likely to be round 11 feet (3.5 meters), but might have reached as much as 16.4 feet (5 meters) (Unwin 201, page 208).

The North American Species

In January 2013, fossil prospector Brent Dunn discovered the front of a pterosaur’s upper jaw (collection ID code: SMU 76892) near Lewisville Lake in northern Texas. These rocks are part of the Britton Formation which are dated to the upper part of the Cenomanian Stage, and the particular rock layer that the jawbone was found in dated to 94 MYA. Two years later, it was named as a new North American species of Cimoliopterus, named C. dunni in honor of Mr. Brent Dunn who found the fossil (Myers 2015, page 1; “New toothed pterosaur identified from North America’s Cretaceous”). The North American species had a crest which was positioned further forwards on the top of the jaw compared to the crest seen on the European species.

The front of the upper jaw of Cimoliopterus dunni. Scale bar = 5 cm. Myers, Timothy S. (2015). “First North American occurrence of the toothed pteranodontoid pterosaur Cimoliopterus“. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 35, issue 6 (November 4, 2015). Page 3.

Possible Additional Specimens

Teeth which have been ascribed to an ornithocheirid pterosaur (species undetermined) have been found within the Twin Mountains Formation and the overlying Paw Paw Formation, both of which are also located in Texas (Myers 2017). It’s possible that these teeth belong to Cimoliopterus dunni. If this is true, then this would push the biostratigraphic range of this species further back to 110 MYA. Another possibility is that they could belong to Uktenadactylus wadleighi, another ornithocheirid pterosaur which was known to inhabit Texas around 100 MYA. The problem is that pterosaur teeth aren’t that distinctive between multiple taxa within the same pterosaur family, so at the moment, it cannot be determined which particular genus or species these teeth belong to.

Also, a single finger bone from an unidentified pterosaur was discovered in the year 2000 in eastern Utah within the rocks of the lowermost strata of the Mussentuchit Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation (Carpenter et al 2008, page 1,089; Kirkland et al 2016, page 153). The Mussentuchit Member is the uppermost member of the formation and dates to about 97-95 MYA. The specimen was discovered by Dr. Reese Barrick of Fort Hays State University, and it is currently held in the collections of the Prehistoric Museum in Price, Utah. According to an e-mail which I received from Dr. Barrick dated to February 15, 2022 in response to an inquiry which I sent to him concerning this specimen, the bone was recovered from an Eolambia nesting ground which was located within the lowermost part of the Mussentuchit Member (NOT the underlying Ruby Ranch Member, as was stated in Kirkland et al 2016). He also stated that the finger bone measured between 20-25 cm long – the length hadn’t been recorded when it was found, and Dr. Barrick was recalling the measurement from memory, which is all the more impressive considering he was trying to remember the length of a fossil he had found twenty-two years ago. According to an e-mail which I received from Dr. Joshua Lively, the paleontology curator at the Prehistoric Museum, dated to March 29, 2022, the bone in question was a “digit IV, phalanx I”, meaning that it was the first finger bone within the very long fourth finger which made up the majority of the animal’s wing. He furthermore stated that the fossil was recovered from the “Eolambia 2 Quarry” (NOT the “Price River 2 Quarry” or “PR-2 Quarry” as was stated in Carpenter et al 2008). It’s possible that this isolated finger bone from Utah could be another specimen of either Cimoliopterus dunni or Uktenadactylus wadleighi. However, there are no finger bones within the holotype specimen from either taxon which we can compare this bone to, so this proposal will have to remain merely as speculation. At present, this finger bone ought to be listed as “Pterosauria digit IV, phalanx I, sp. indet.”, meaning “Pterosaur, fourth finger, first finger bone, species undetermined”.

Seaside Life in the Middle Cretaceous

If Cimoliopterus was primarily a seacoast-dwelling fish-eater, as many paleontologists think ornithocheirid pterosaurs were, then there were plenty of options to choose from on its prehistoric menu.

In southern England around 100 MYA, where C. cuvieri roamed the skies, there was a vast diversity of marine life. The majority of the marine fossils found within the Ammonites varians zone of the Grey Chalk Subgroup are ammonite, belemnite, nautilus, bivalve, and gastropod shells – a very mollusk-rich ecosystem (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, pages 24-31, 38). However other marine invertebrates lived here, too, including the sea sponges Stauronema carteri (only found in Bed 1), Plocoscyphia fenestrata (only found in Bed 2), and Plocoscyphia labrosa (found in Beds 1 and 2) (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, pages 37-39), the sea urchin Cidaris sp. (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, page 72), and the annelid tube worm Serpula umbonata (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, page 50). Fish fossils within the Ammonites varians zone are rare, but they have nevertheless been found. These include the chimaera ratfishes Edaphodon sp. (Bed 2) and Ischyodus sp. (Bed 4) (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, page 44), the coelacanth Macropoma sp. (Bed 4) (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, page 44), the plethodid fish Plethodus expansus (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, page 70), the bonefish Albula (formerly Pisodus) sp. (Bed 4) (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, page 44), the pachyrhizodont fish Pachyrhizodus (formerly Acrodontosaurus) gardneri (Bed 2) (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, page 44, 50), and the swordfish-like pachycormid Protosphyraena ferox (Bed 2) (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, page 44). Fossils have been discovered belonging to several species of sharks including the “Crow Shark” Squalicorax falcatus (Bed 3) (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, pages 25, 39), the “Ginsu Shark” Cretoxyrhina mantelli (Bed 3) (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, pages 25, 39), the megatooth shark Cretalamna appendiculata (Beds 1 and 4) (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, pages 25, 44), and the seven-gill shark Notidanus microdon (Bed 3) (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, pages 25, 39). Marine reptiles include the 5.8 meter (19 foot) long ichthyosaur Pervushovisaurus campylodon (formerly classified as a species of Ichthyosaurus) (only found within Bed 2) and the 7 meter (23 foot) long pliosaur Polyptychodon interruptus (Jukes-Brown and Hill 1903, pages 25, 39, 44).

As far as the North American species C. dunni goes, in freshwater, you had the 1.5 foot long tetra Erythrinolepis mowriensis (Cockerell 1919, page 182; Schaeffer 1947, page 27; Novacek and Marshall 1976, pages 1-12), the 3 foot long lungfish Ceratodus, amiid bowfins, semionotids, and possibly the 3 foot long gar Lepisosteus (Kirkland et al 2016, page 160). In saltwater, you had schools of herring-like Holcolepis, the 20 inch long armored enchodont Halecodon, the 2 foot long mackerel-like fish Pelecorapis, and the ancient salmon relative Leucichthyops. But Cimoliopterus dunni needed to be careful in flying too low to the water’s surface to snap them up, because also swimming in the sea was the 18 foot long predatory fish Xiphactinus, which would have gladly grabbed anything that came within its toothy grasp (Cockerell 1919, pages 173-181; Bardack 1965, pages 11, 37, 52, 61-62). The Mowry Sea was also home to several species of marine reptiles who likely would not have passed up the chance to take down a small pterosaur that flew a bit too low.

However, there is evidence to suggest that the ornithocheirids did not eat an exclusively piscivorous diet. In 2017, a study was published concerning the chemical trace elements left within the enamel of the teeth of ornithocheirid pterosaurs, and the results were surprising. According to this study’s findings, the trace elements are more indicative of terrestrial prey rather than aquatic prey, indicating that the ornithocheirids had a much more varied diet rather than relying exclusively on fish (Myers 2017).

Artwork

Below is an illustration which I made of Cimoliopterus cuvieri and Cimoliopterus dunni. The shape of the rest of the skull and the overall shape of the body are based strongly on the related pterosaur genus Anhanguera blittersdorffi. The coloration is based upon the Pacific Gull (Larus pacificus).

Cimoliopterus cuvieri (top left) and Cimoliopterus dunni (bottom right). © Jason R. Abdale (March 2, 2024).

If you enjoy these drawings and articles, please click the “like” button, and leave a comment to let me know what you think. Subscribe to this blog if you wish to be immediately informed whenever a new post is published. Kindly check out my pages on Redbubble and Fine Art America if you want to purchase merch of my artwork.

Bibliography

Books

Jukes-Brown, Alfred John; Hill, William. The Cretaceous Rocks of Britain, Volume II: The Lower and Middle Chalk of England. London: Wyman and Sons, Ltd., 1903.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Cretaceous_Rocks_of_Britain_The_Lowe/hHARAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Owen, Richard. A History of British Fossil Reptiles, Volume 1. London: Cassell & Company, Ltd., 1884.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_History_of_British_Fossil_Reptiles/NTJYAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Pterodactylus+cuvieri&pg=PA380&printsec=frontcover.

Seeley, Harry G. The Ornithosauria: an elementary study of the bones of pterodactyls, made from fossil remains found in the Cambridge Upper Greensand, and arranged in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge. Cambridge: Deighton, Bell, and Co., 1870.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/52655/52655-h/52655-h.htm.

Articles

Bowerbank, J. S. (1851). “On the Pterodactyles of the Chalk Formation”. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, volume 19 (January 14, 1851). Pages 1-7.

https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=6i4-AAAAcAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP6&ots=bj39mvLhY3&sig=9J8YdIyGq_6GroWxCgOwa7HuYes#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Carpenter, Kenneth; Bartlett, Jeff; Bird, John; Barrick, Reese (2008). “Ankylosaurs from the Price River Quarries, Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous), East-Central Utah”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 28, issue 4 (December 2008). Pages 1,089-1,101.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249022968_Ankylosaurs_from_the_Price_River_Quarries_Cedar_Mountain_Formation_Lower_Cretaceous_East-Central_Utah.

Cockerell, T. D. A. (1919). “Some American Cretaceous fish scales, with notes on the classification and distribution of Cretaceous fishes”. U. S. Geological Survey. Shorter Contributions to General Geology, professional paper 120. Pages 165-206.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Professional_Paper/43fdNoV0ybIC?hl=en&gbpv=0.

Duque, Rudah Ruano C.; Pinheiro, Felipe L.; Barreto, Alcina Magnólia Franca (2022). “The ontogenetic growth of Anhangueridae (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea) premaxillary crests as revealed by a crestless Anhanguera specimen”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 42, issue 1 (October 11, 2022): e2116984.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364323587_The_ontogenetic_growth_of_Anhangueridae_Pterosauria_Pterodactyloidea_premaxillary_crests_as_revealed_by_a_crestless_Anhanguera_specimen.

Kirkland, James I.; Suarez, Marina; Suarez, Celina; Hunt-Foster, ReBecca (2016). “The Lower Cretaceous in East-Central Utah—The Cedar Mountain Formation and its Bounding Strata”. Geology of the Intermountain West, volume 3 (October 2016). Pages 101-228.

https://giw.utahgeology.org/giw/index.php/GIW/article/view/11.

Myers, Timothy S. (2015). “First North American occurrence of the toothed pteranodontoid pterosaur Cimoliopterus“. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 35, issue 6 (November 4, 2015). Pages 1-9.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283490473_First_North_American_occurrence_of_the_toothed_pteranodontoid_pterosaur_Cimoliopterus.

Myers, Timothy S. (2017). “Diet of ornithocheirid pterosaurs inferred from stable carbon isotope analysis of tooth enamel”. GSA Annual Meeting in Seattle, Washington, USA (January 2017).

https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2017AM/webprogram/Paper305496.html.

Novacek, Michael J.; Marshall, Larry G. (1976). “Early Biogeographic History of Ostariophysan Fishes”. Copeia, volume 1976, issue 1 (March 12, 1976). Pages 1-12.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1443767.

Owen, Richard (1859). “On Remains of New and Gigantic Species of Pterodactyle (Pter. Fittoni and Pter. Sedgewickii) from the Upper Greensand, near Cambridge”. Report of the Twenty-Eighth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (1859). Pages 98-103.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Report_of_the_Meeting/FuJJAAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Pêgas, Rodrigo V.; Holgado, Borja; Leal, Maria E. C. (2019). “On Targaryendraco wiedenrothi gen. nov. (Pterodactyloidea, Pteranodontoidea, Lanceodontia) and recognition of a new cosmopolitan lineage of Cretaceous toothed pterodactyloids”. Historical Biology, volume 33, issue 4 (November 2019). Pages 1-15.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337363603_On_Targaryendraco_wiedenrothi_gen_nov_Pterodactyloidea_Pteranodontoidea_Lanceodontia_and_recognition_of_a_new_cosmopolitan_lineage_of_Cretaceous_toothed_pterodactyloids.

Rodrigues, Taissa; Kellner, Alexander Wilhelm Armin (2013). “Taxonomic review of the Ornithocheirus complex (Pterosauria) from the Cretaceous of England”. Zookeys, volume 308 (June 12, 2013). 1-112.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3689139/.

Schaeffer, Bobb (1947). “Cretaceous and Tertiary Actinopterygian Fishes from Brazil”. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, volume 89, article 1 (April 30, 1947). Pages 1-40.

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/18222965.pdf.

Unwin, David M. (2001). “An overview of the pterosaur assemblage from the Cambridge Greensand (Cretaceous) of Eastern England”. Mitteilungen aus dem Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, Geowissenschaftliche Reihe volume 4 (November 5, 2001). Pages 189-221.

https://fr.copernicus.org/articles/4/189/2001/fr-4-189-2001.pdf.

Websites

Phys.org. “New toothed pterosaur identified from North America’s Cretaceous” (December 8, 2015).

https://phys.org/news/2015-12-toothed-pterosaur-north-america-cretaceous.html.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment