Introduction

Siats, whose name is in reference to a monster from native Ute folklore, was a large meat-eating dinosaur which lived in Utah during the middle Cretaceous Period 98 million years ago. As far as we know, Siats was the last large non-tyrannosaur theropod dinosaur which lived in North America. Up to this time, North American tyrannosaurs were small wolf-like predators, such as Stokesosaurus, Suskityrannus, and Moros. After Siats went extinct, this opened up an ecological niche which the tyrannosaurs could exploit – they grew larger, more muscular, more powerful, and quickly became the dominant terrestrial carnivores within North America.

Discovery

In 2008, a paleontological expedition from the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois was prospecting for fossils within Emery County, Utah, and a few fossil bones were spotted sticking out of the ground. The fossils were found within the rocks of the Mussentuchit Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation. The stratum was dated to 98 MYA, within the Cenomanian Stage of the middle Cretaceous Period. Official government permits were needed to conduct a full excavation of the site, which weren’t approved until the following year. These fossils, which were all disarticulated from each other, were excavated during the 2009 and 2010 dig seasons, and were brought back to the Field Museum’s labs for preparation and analysis (“Scientists Discover a New Dinosaur! Siats”; Zanno and Makovicky 2013: 2827).

The fossils which were found consisted of a few dorsal vertebrae, a partial right ilium, a partial left and partial right ischium, the middle of a leg bone, a handful of toe bones, and few tail vertebrae. Furthermore, most of the bones were damaged and were missing bits and pieces. Examination of these fossils showed that they belonged to a large meat-eating dinosaur. Up until that point, the largest meat-eater which lived in North America during the middle Cretaceous was the 35 foot long Acrocanthosaurus, whose remains have been found in several places across North America in rocks dated 115-110 MYA. However, the fossils that had been found in Utah didn’t resemble those belonging to Acrocanthosaurus, and they were also several million years younger than the youngest-known Acro specimen. Although only a few fossils were found in Emery County, the anatomical features present upon the bones were distinctive enough to warrant naming this animal as a new genus. In November 2013, this new dinosaur was officially named Siats meekerorum. The genus name Siats is named after a man-eating monster from native Ute mythology; apparently, the correct pronunciation of its name is SEE-aahtch, not SEE-ats, as I had always thought. The species name meekerorum honors the Meeker family who funded paleontological work at the Field Museum. The holotype specimen is currently held in the collections of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois (collection ID code: FMNH PR 2716) (Zanno and Makovicky 2013: 2827).

Description

The official species diagnosis for Siats meekerorum reads as follows:

“Large-bodied allosauroid exhibiting craniocaudally expanded centrodiapophyseal laminae yet lacking well-developed infradiapophyseal fossae on proximal caudals (autapomorphy); craniocaudal elongation of craniodorsal centra; abbreviated, transversely broad neural spines on dorsal vertebrae (neural spine height ~50% maximum height of centrum); transversely flattened, axially concave ventral surface yielding subtriangular cross-section on distal caudal vertebrae (autapomorphy); transversely concave acetabular rim of iliac pubic peduncle (autapomorphy); truncated lateral brevis shelf with notched caudal end (autapomorphy); brevis fossa with subparallel mediolateral margins; supraacetabular crest truncated above midpoint of acetabular rim” (Zanno and Makovicky 2013: 2827).

As you can see from the previous paragraph, several anatomical features upon the bones were classified as “autopomorphies” – unique anatomical features which are only found in one particular species. Autopomorphies are used by paleontologists to identify which species a bone belongs to.

It was noted in Zanno’s and Makovicky’s 2013 report that the dorsal vertebrae are structurally similar to the dorsal vertebrae seen in Neovenator and Aerosteon. The pelvic elements seem to be more similar to those belonging to megalosaurids, metriacanthosaurids, and in Neovenator. The tail vertebrae seem to be most similar to Sinraptor and other primitive allosauroids. (Zanno and Makovicky 2013: 2827). A few isolated teeth were also found scattered nearby, which might belong to Siats, but we can’t be sure (Zanno and Makovicky 2013: 2827).

The vertebrae’s neural arches were unfused, indicating that this individual was not fully grown (Zanno and Makovicky 2013: 2827). The animal possibly measured 30-35 feet long, but that’s only an estimate. However, this measurement is based upon the idea that this animal is a neovenatorid allosaur. But was it?

Problems with Classification

In 2013, Siats was classified as a carcharodontosaur, and specifically a neovenatorid, closely related to Neovenator of southern England. This identification was based principally upon the highly pneumatic structure of the vertebrae and the distinctive “peg-and-socket” joint of the articulation between the ilium and ischium (Zanno and Makovicky 2013: 2827).

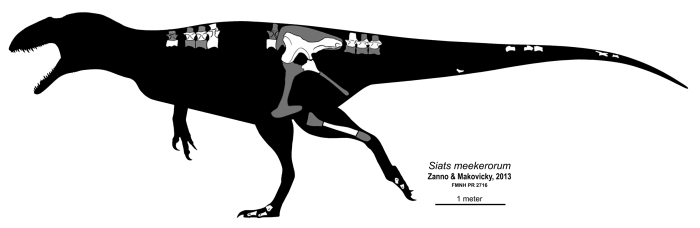

Fossils of Siats, here portrayed as a neovenatorid allosauroidean. Based upon FMNH PR 2716 and FMNH PR 3059.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Siats_meekerorum_skeletal_diagram.jpg.

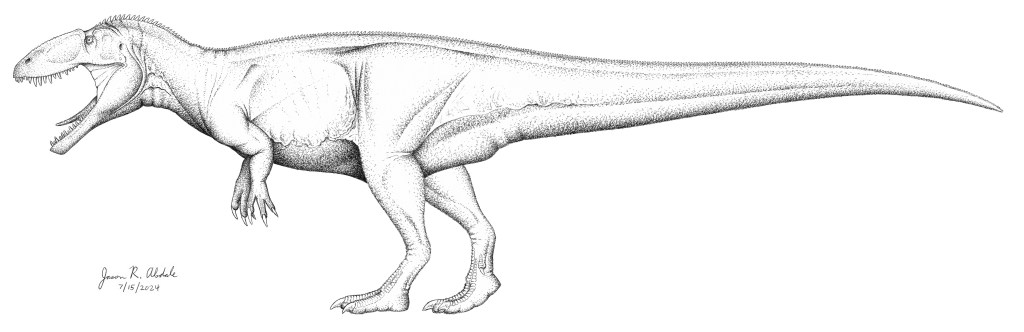

Siats meekerorum portrayed as a carcharodontosaur. © Jason R. Abdale (July 15, 2024).

However, there is also evidence that Siats might have been a megaraptoran. Indeed, in 2013, the megaraptorans were thought to be a sub-group of the carcharodontosaur family Neovenatoridae. The classification of Siats as a megaraptoran was based upon “pronounced centrodiapophyseal laminae bracketed by deep infradiapophyseal fossa on the caudal neural arches” (Zanno and Makovicky 2013: 2827), which was regarded as an anatomical feature present within megaraptoran theropods such as Megaraptor itself and Aerosteon, which Siats‘ vertebrae bore a few similarities to. Even so, Zanno and Makovicky stated that Siats‘ identification as a megaraptoran was uncertain and could be changed in the future (Zanno and Makovicky 2013: 2827).

In 2010, the family Neovenatoridae was created as a clade within Allosauroidea. This family encompassed Neovenator, Aerosteon, Australovenator, Chilantaisaurus, Fukuiraptor, Orkoraptor, and Megaraptor. The majority of these genera are now classified as megaraptorans, and in 2010, the megaraptorans were believed to be highly-derived allosaurs. The very same report also stated that Neovenator itself, the namesake specimen of Neovenatoridae, was unequivocally an allosauroid and also was either a carcharodontosaur or a close relative. In 2007, it was stated that Megaraptor was a carcharodontosaur, and an earlier report made in 1998 stated that its close relative Aerosteon was also a carcharodontosaur (Benson et al 2010, pages 71-72).

While the megaraptorans were thought of for some time to be nested within the clade Carcharodontosauria, they are now thought of by some paleontologists to actually be distant cousins of the tyrannosaurs, and therefore they likely had primitive feathers on their bodies. Recent studies have suggested that the megaraptorans are a group within the clade Coelurosauria, just like the tyrannosaurs are. In fact, Rolando et al (2022) stated that the megaraptorans are the sister group to the tyrannosauroids (Novas et al 2012, page R33; Porfiri et al 2014, pages 35-55; Apesteguía et al 2016: e0157793; Rolando et al 2022: 6318).

The lack of a clear answer as to what sort of an animal Siats was is largely due to the sparse nature of the remains. Only a few bones were found, and nearly all of them were damaged. Even so, while there is some evidence to suggest that Siats was a megaraptoran, there is more evidence to suggest that it was a carcharodontosaur.

In 2022, an extensive survey of the early Cretaceous tyrannosauroid Eotyrannus lengi was published. Within this article, it stated that the megaraptorans were a group within the super-family Tyrannosauroidea, and further stated that Siats was a basal member of Megaraptora (Naish and Cau 2022: e12727).

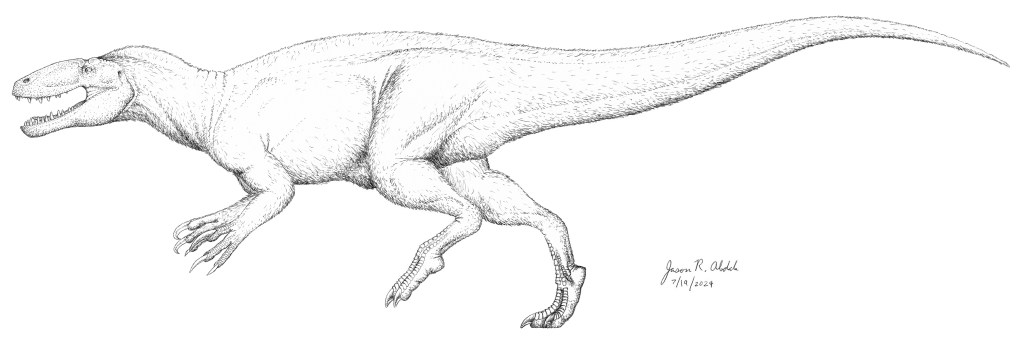

Siats meekerorum portrayed as a megaraptoran. © Jason R. Abdale (July 19, 2024).

Paleo-Ecology: Utah during the Middle Cretaceous Period 100-95 Million Years Ago

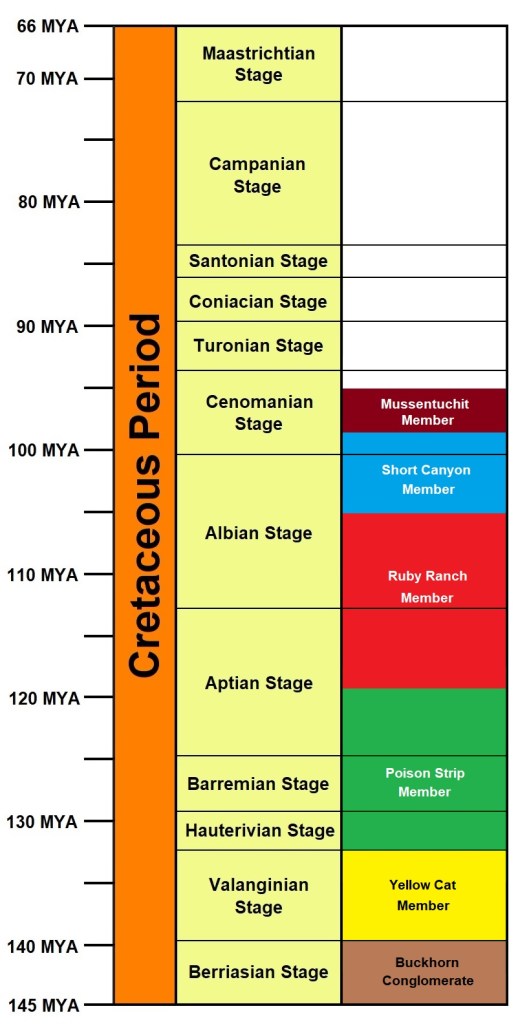

Siats‘ fossils were found within the Mussentuchit Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation. The Mussentuchit Member is the uppermost level of the formation, and dates to the Cenomanian Stage of the middle of the Cretaceous Period. Different papers which have been published over the years have ascribed different dates to this geological member, but the majority state that the Mussentuchit sits within the Cenomanian Stage. Siats‘ fossils were found in the lowermost level of the Mussentuchit Member, close to the contact with the underlying Short Canyon Member. Note that some paleontologists and geologists don’t consider the Short Canyon Member to be an actual separate geological member, and instead consider it to be part of the Mussentuchit Member.

Geochronology of the members of the Cedar Mountain Formation, based on dates given in Kirkland et al (2016), Joeckel et al (2019), Phillips et al (2021), and Joeckel et al (2023). Image by Jason R. Abdale (2022).

During the 1970s, thanks to fossil finds in North America which are traditionally associated with the early Cretaceous of Europe, it was proposed that western Europe was connected to the northern part of North America during the early Cretaceous Period via a trans-Atlantic land bridge (Galton and Jensen 1975, pages 668-669; Galton and Jensen 1979, pages 1-10). Numerous scientific studies carried out during the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s re-affirmed this (Kirkland et al 2016, pages 138, 154; Royo-Torres et al 2017: 14311). In particular, Leonidas Brikiatis’ 2016 report was the most thorough. In it, he states that it wasn’t until 129 MYA that the ever-growing Atlantic Ocean expanded to such an extent that North America was at last permanently severed from Europe. For a period afterwards measuring approximately twenty-five or so million years, North America was completely isolated from the rest of the Mesozoic world. It wouldn’t be until the late Albian Stage about 105-100 MYA that a second land bridge appeared, this time spanning the northern Pacific, connecting Alaska with Russia (Brikiatis 2016, pages 47-57). This new Pacific land bridge which connected Asia with North America ushered in a new period of species migrating between the two continents (the scientific term for this is “faunal interchange”), and explains why traditionally Asian fauna such as oviraptorosaurs and ceratopsians suddenly appeared in North America from about 100 MYA onwards.

So if Siats really is a megaraptoran as it has been suggested, and if megaraptorans are mostly known from the Southern Hemisphere, then how did one get into North America? Its ancestors had to have been present within North America either prior to the submergence of the Trans-Atlantic Land Bridge in 129 MYA, or they had to have come into North America from eastern Asia via the North Pacific Land Bridge around 105-100 MYA. This second option seems more likely, because there are two megaraptorans known from the Northern Hemisphere: Fukuiraptor from Japan and Phuwiangvenator from Thailand. Fukuiraptor’s fossils have been found within the Kitadani Formation, which dates 125-115 MYA, and Phuwiangvenator was found within the Sao Khua Formation in rocks dating 125-120 MYA. It’s therefore possible that Asian megaraptorans could have migrated from eastern Asia across the North Pacific Land Bridge and into North America sometime after 105-100 MYA.

A sharp increase in global temperatures occurred during this time called the “Cretaceous Thermal Maximum” (Jones et al 2022, 954-958; Zanno et al 2023). In general, the climate was similar to the tropics. Utah became a lot hotter and more humid during the Cenomanian Stage of the middle Cretaceous, leading to increased rainfall and increased water output from rivers. Average precipitation was 1,278 mm per year, but it might have gotten as high as 1,870 mm per year (Suarez et al 2012; 2014; Kirkland et al 2016, pages 166-167).

The humidity was compounded even further by eastern Utah’s close proximity to the shoreline of the Mowry Sea. This was a body of Arctic saltwater which had penetrated into North America from the Mackenzie River Basin in northern Canada, and had been steadily encroaching further and further southwards and expanding wider and wider across the center of North America with every passing year (Jeletzky 1971, pages v., 42-49). Geological evidence suggests that the Mowry Sea was murky and muddy, and had poor oxygen levels; modern-day analogies to such an environment would be the Mississippi Delta, the waters of New York Harbor, and the western half of the Long Island Sound (Jeletzky 1971, page v.; Bergendahl et al 1960, pages 647-651; Stewart and Hakel 2006, page 161; Sprinkel et al 2012, Page 12). At the same time that the Mowry Sea was expanding, the Gulf of Mexico was also increasing in size due to tectonic shift and rising sea levels, moving further and further northwards. Only a narrow land bridge spanning what’s now southern Colorado and northern New Mexico known as the Transcontinental Arch separated these two water bodies from each other and connected the western and eastern halves of the continent. Sometime during the late Cenomanian and early Turonian Stages, both the Mowry Sea and the Gulf of Mexico dramatically grew in size in an event known as the Greenhorn Transgression. The Mowry Sea would merge with the Gulf of Mexico, creating the Western Interior Seaway, and split North America completely in half (Slattery et al 2013, pages 28, 36, 38-39; Elderbak et al 2014, page 29). The exact date when the joining of the northern and southern seas occurred has been subject to a lot of discussion over the decades, with different articles giving different dates as to when it happened. Robinson-Roberts and Kirschbaum (1995) states that the creation of the Western Interior Seaway occurred during the Neogastroplites cornutus biostratigraphic zone at the beginning of the Cenomanian Stage (Robinson-Roberts and Kirschbaum 1995, pages 5, 15). Slattery et al (2013) states that the Mowry Sea and the Gulf of Mexico joined during the Neogastroplites maclearni biostratigraphic horizon (Slattery et al 2013, page 39), and elsewhere in the article during the Neocardioceras juddii biostratigraphic horizon (Slattery et al 2013, page 40). Neogastroplites maclearni was a species of ammonite whose fossil shells are found within the uppermost layer of the Mowry Shale (Reeside Jr. and Cobban 1960, page 27). The ammonite Neocardioceras juddii lived during the late Cenomanian around 93 MYA (“Neocardioceras juddii”). Most recently in 2023, it was stated that the Greenhorn Transgression took place during the late Cenomanian Stage between 94.6-94.0 MYA based upon the dating of zircons found within volcanic sediments (Renaut et al 2023).

Map of North America during Neogastroplites cornutus biostratigraphic zone of the early Cenomanian Stage, middle Cretaceous Period, 99 MYA. Slattery, Joshua S.; Cobban, William A.; McKinney, Kevin C.; Harries, Peter J.; Sandness, Ashley L. (2013). “Early Cretaceous to Paleocene Paleogeography of the Western Interior Seaway: The Interaction of Eustasy and Tectonism”. Wyoming Geological Association, 68th Annual Field Conference (June 2013). Page 38.

Map of North America during the Neocardioceras juddii biostratigraphic zone of the late Cenomanian Stage, middle Cretaceous Period, 93 MYA. Slattery, Joshua S.; Cobban, William A.; McKinney, Kevin C.; Harries, Peter J.; Sandness, Ashley L. (2013). “Early Cretaceous to Paleocene Paleogeography of the Western Interior Seaway: The Interaction of Eustasy and Tectonism”. Wyoming Geological Association, 68th Annual Field Conference (June 2013). Page 40.

Siats might have been the largest carnivore within western North America during the Cenomanian Stage of the middle Cretaceous Period. However, Siats wasn’t the only large theropod in its ecosystem. Living alongside it was a massive oviraptorosaur which may be Gigantoraptor. Gigantoraptor erlianensis was a massive 25-30 foot long oviraptorosaurian theropod dinosaur which lived in eastern Asia and possibly in North America during the middle of the Cretaceous Period about 95 MYA (Xu et al 2007, pages 844-847). Two individuals of this animal are known from Asia, which include a partial skeleton from China and a single jaw bone from Mongolia (Tsuihiji et al 2015, pages 60-65; Molina-Perez and Larramendi 2019, page 54). Large eggs which were found in China and South Korea in rocks dated to the middle Cretaceous may also belong to Gigantoraptor (Zelenitsky et al 2000, pages 130-131; Huh 2014, page 151). These eggs were given the name Macroelongatoolithus, which literally translates to “huge elongated egg-stone”. As the name suggests, these eggs were very large, measuring almost two feet long, and clearly belonged to a large animal. During the 1960s and 1990s, similar eggshell fragments were discovered in Utah within the rocks of the Mussentuchit Member (Jensen 1970, pages 51-65; Zelenitsky et al 2000, pages 130-138). Similar eggs were also found in Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and Nevada (Bonde et al 2008, pages 255, 260; Simon 2014, pages 1-110; Simon et al 2018: e1553046). Then in 2012, a partial skeleton was found in Utah within the Mussentuchit Member. The bones were very similar to Gigantoraptor (Makovicky et al 2014, page 175; Makovicky et al 2023). In 2016 at a place called “Deep Eddy” in Emery County, Utah, a nest was discovered with intact eggs measuring almost a foot long. These eggs were determined to belong to a large oviraptorosaurian (Hedge and Zanno 2023), possibly to Gigantoraptor erlianensis or another closely-related species.

Another carnivore which shared Siats‘ world was the 10 foot long tyrannosauroid Moros. During the middle and late 1990s, it was fleetingly reported in several scientific articles that tyrannosauroid teeth had been found within the Mussentuchit Member, but very little information – if any – accompanied the mere mention of their discovery (Kirkland et al 1999, page 213). These teeth were used as evidence that tyrannosauroid theropods had migrated into North America from Asia sometime during the middle of the Cretaceous Period, but even so, the evidence for such a claim was slim. It wasn’t until 2013 that a partial right leg was discovered in the Mussentuchit Member which was shown to belong to a primitive tyrannosaur (“New tiny tyrannosaur helps show how T. rex got big”). Due to a similarity of the leg bones to those of the Asian species Alectrosaurus which lived around the same time, these fossils were tentatively identified as “Cf. Alectrosaurus“, meaning “similar in shape to Alectrosaurus” (Zanno et al 2023: e0286042). In 2019, it was announced that these bones actually belonged to a completely new genus of small tyrannosaur, and it was officially named Moros intrepidus. Although known from only a right leg and a few teeth, this wolf-like predator seems to have visually resembled Alectrosaurus as well as the lithe long-legged juveniles of animals like Albertosaurus and Gorgosaurus (Zanno et al 2019, pages 1-12). A tyrannosaur femur recovered from the Wanyan Formation of Idaho, which dates to the same time as the Mussentuchit Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation, might belong to Moros, or it could possibly belong to another small tyrannosauroid theropod (Krumenacker et al 2022, pages 1,336-1,345).

Siats and Moros had abundant prey choices to choose from. The most common plant-eating dinosaur in this ecosystem was the 20 foot long primitive hadrosaur Eolambia caroljonesa. This animal is known from abundant remains found in two bonebeds. Evidence of this animal’s existence was first published in 1994, and it was noted in 1999 that it bore a resemblance to the European dwarf hadrosaur Telmatosaurus (Kirkland et al 1999, page 213). Remarkably, many features of Eolambia’s anatomy suggest that it is more closely related to Asian hadrosaurs than to North American ones, once again affirming that there was a land bridge connecting Asia and North America around 100 MYA (Kirkland 1998, pages 283-295; McDonald et al 2012: e45712).

Living alongside Eolambia was the 12 foot long rhabdodont Iani smithi (Zanno et al 2023: e0286042). The rhabdodonts (or more broadly, the rhabdodontomorphs) are a group primarily known from Europe and Australia, and they are largely dated to the late Cretaceous Period. It’s curious that one was found in North America, and that leads to an interesting question: Where did the rhabdodontomorphs originate? Since the majority of rhabdodontomorph species are found in Europe, one is tempted to say that they originated there. However, the earliest-known rhabdodontomorphs aren’t found in Europe: Muttaburrasaurus is from Australia, and Tenontosaurus is from North America, and both species date to about 110 MYA. Since the Trans-Atlantic Land Bridge which connected North America with Europe was submerged around 129 MYA, and since the North Pacific Land Bridge which connected Russia and Alaska didn’t form until 105-100 MYA, this would mean that the rhabdodontomorphs were already present within North America sometime before 129 MYA, when North America split off from Europe. This means that there may be as-yet-undiscovered rhabdodontomorph dinosaurs within North America in rocks dated to the early Cretaceous Period dated to 129 MYA or earlier.

Scampering along the fringes of the forests like herds of deer was a species of thescelosaurine “hypsilophodont” dinosaur named Fona herzogae. Ten individuals have been uncovered from five different localities within the Mussentuchit Member. This particular species appears to be related more to Asian species than to North American ones, providing further evidence of faunal interchange between Asia and North America during the middle Cretaceous (Makovicky et al 2014, page 175; Avrahami et al 2019, pages 56-57; Avrahami et al 2023). Based upon the size of the fossils, and comparing them to the skeletons of other theselosaurines, Fona likely measured 7 feet long (Avrahami et al 2024, e25505).

Sauropod teeth have been found within the Mussentuchit Member which appear to be most similar to teeth belonging to brachiosaurs. About twenty teeth were collected from two localities within the Mussentuchit Member. Articles which were published in 1997 and 1999 simply described the teeth as being similar in shape to those belonging to the mid-Cretaceous sauropod Astrodon, although the teeth recovered from Utah were substantially smaller (Cifelli et al 1997, pages 11,163-11,167; Kirkland et al 1997, pages 79-81; Cifelli et al 1999, pages 225, 231; Kirkland et al 1999, pages 211, 213). Due to the small size of the teeth, it was proposed that the teeth might belong to a dwarf brachiosaur species, but there’s hardly any evidence to support that idea (Maxwell and Cifelli 2000, pages 19-24; Kirkland et al 2016, page 162). These teeth might belong to Abydosaurus, which is a brachiosaurid sauropod which lived during the underlying Ruby Ranch Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation, and which measured approximately 60 feet long. The 2010 article which named it stated that the bones were found within the lowermost level of the Mussentuchit Member, but were dated to 104.5 MYA, give or take.

Several species of armored dinosaurs lived in western North America during this time including Animantarx, Nodosaurus, and Peloroplites. Both Animantarx and Peloroplites are known from Utah while Nodosaurus is known from Wyoming. Animantarx was found within the Mussentuchit Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation at a place called “Carol Site”, a few miles east of Castle Dale, Utah. The fragmentary remains were shown to be similar to Silvisaurus and Pawpawsaurus, and it’s possible that these three genera were closely related to each other. Based upon the size of the scant remains and comparing them to other ankylosaurs, Animantarx appears to have been a rather small dinosaur, measuring just 10-12 feet long (Carpenter et al 1999, pages 243-248). By contrast, Peloroplites was twice the size at 20 feet long. Peloroplites was found at the very base of the Mussentuchit Member within the “Price River II Quarry” (Carpenter et al 2008, pages 1,089-1,101; Avrahami et al 2018: e5883). Fragmentary fossils of Nodosaurus were found in Wyoming within rocks of the Belle Fourche Member of the Frontier Formation, dated to approximately 95 million years ago. Nodosaurus was depicted for decades in paleo-art as an armadillo-like creature whose body was covered in row-upon-row of small oval or square-shaped osteoderms. However, more complete fossils from other nodosaurid genera show that Nodosaurus‘ appearance was more elaborate, and it probably bore more of a resemblance to Borealopelta or Struthiosaurus, with large spines on its neck and shoulders (Carpenter et al 1998, 249-253).

Teeth which have been identified as belonging to an indeterminate species of neoceratopsian have been found in the Mussentuchit Member. These teeth were noted as being most similar in form to Leptoceratops, Montanaceratops, and/or Udanoceratops (Chinnery et al 1998, pages 297-302). All three of the aforementioned genera belong to the family Leptoceratopsidae. Therefore, it is very likely that the neoceratopsian teeth recovered from the Mussentuchit Member also belong to an as-yet-unidentified leptoceratopsid. Afterwards, an ilium from a juvenile neoceratopsian was recovered from the upper part of the Mussentuchit Member. This ilium most closely resembles that belonging to Agujaceratops mariscalensis from the Campanian-aged Aguja Formation of southern Texas (Carpenter and Cifelli 2016, pages 167-175). Agujaceratops is a close relative of Chasmosaurus. In 2023, it was announced that a partial skeleton of “an early-diverging neoceratopsian” had been found within the Mussentuchit Member, but no further information was given (Zanno et al 2023).

Within the Mussentuchit Member, teeth have been found which might belong to a primitive pachycephalosaur. (Cifelli et al 1997, pages 11,163-11,167; Kirkland et al 1997, pages 79-80). Regrettably, no further evidence of this has been discovered.

Pterosaur fossils from the Mussentuchit Member are extremely scant. So far, only one bone from a pterosaur has been found within these rock layers – a single finger bone which perhaps belongs to Cimoliopterus dunni, which is known to have inhabited Texas during that time (Carpenter et al 2008, page 1,089; Kirkland et al 2016, page 153).

At least eight species of lizards dwelt here including four teiids, two skinks, and the intriguing Primaderma nessovi which belonged in the same clade as monitor lizards and gila monsters, which means it likely had a venomous bite! Living alongside them was also the primitive snake Coniophis (Cifelli et al 1997, pages 11,163-11,167; Kirkland et al 2016, page 161).

Several species of fish, amphibians, and aquatic reptiles are known from these rock layers. In freshwater, you had the 18 inch long tetra Erythrinolepis mowriensis (Cockerell 1919, page 182; Schaeffer 1947, page 27; Novacek and Marshall 1976, pages 1-12), the 3 foot long lungfish Ceratodus molossus (Frederickson & Cifelli, 2019), an amiid bowfin similar to Melvius (Fiorillo 1999, pages 261-262), semionotids, and possibly the 3 foot long gar Lepisosteus. Sharing this aquatic habitat was the salamander Albanerpeton, four species of turtles, and seven species of crocodylomorphs. The crocodylomorph specimens include:

- A species of the genus Bernissartia (Cifelli et al 1999, page 225; Kirkland et al 2016, page 161).

- The goniopholidid Dakotasuchus kingi (Cifelli et al 1999, page 225; Kirkland et al 2016, page 161; Frederickson et al 2017, pages 279-286).

- A second goniopholidid species which was assigned to the genus Polydectes (Cifelli et al 1999, page 225; Kirkland et al 2016, page 161). Polydectes was named by Edward D. Cope in 1869 based upon a single tooth recovered from Campanian-aged strata in North Carolina (Cope 1869, page 192; Miller 1967, pages 230-231). Polydectes is now regarded as a synonym of the 40 foot long alligator relative Deinosuchus (Schwimmer 2002, page 40; “Polydectes biturgidus Cope, 1869”). It’s possible that this second goniopholidid specimen from Utah might actually belong to the goniopholidid Diplosaurus vebbii, previously known from Kansas from rock layers dated to about 105 MYA (Owen 1849, page 383; Leidy 1865, pages 18-21; Cope 1868, pages 26, 680; Cook 1868, page 736; Cope 1871, pages 80-82; Cope 1872, pages 325, 327; Cope 1875, pages 16, 67-68; Marsh 1877, page 254; Zittel 1890, page 677; Haworth 1897, page 191; Hay 1902, page 516; Williston 1905, page 346; Todd 1911, page 66; Bassler et al 1916, page 349; Mook 1925, pages 322-324; Troxell 1925, pages 489-514; Buffetaut 1976, pages 333-336; Langston Jr. 1995, page F1; Denton Jr. et al 1997, page 395; Wang 2002, page 23).

- An indeterminate species of atoposaurid, possibly Theriosuchus (Fiorillo 1999, page 266).

- An indeterminate species of pholidosaurid, possibly Terminonaris or a close relative (Adams et al 2011, pages 712-716).

Two indeterminate teleosaurid marine crocodiles, one of which might be a species of Machimosaurus (Cifelli et al 1999, page 225; Kirkland et al 2016, pages 160-161).

Beyond the beach within the murky waters of Mowry Sea 100-95 MYA, you had schools of small herring-like Holcolepis, the larger mackerel-like fishes Apsopelix anglicus and Pelecorapis varius, the 20 inch long armored enchodont Halecodon denticulatus, the 2 foot long prehistoric salmon relative Leucichthyops vagans, and the massive 18 foot long predatory fish Xiphactinus (Cockerell 1919, pages 171-183; Bardack 1965, pages 11, 37, 52, 61-62). Hovering in the water column were the ammonites Metengonoceras, Neogastroplites, and possibly Acanthoceras (Bergendahl et al 1960, pages 650-652; Reeside Jr. and Cobban 1960, pages 1-126; Cobban and Kennedy 1989, pages 1-11; Condon 2000, pages 6-7). Meanwhile, cruising along the sea bottom were the guitarfish Cristomylus nelsoni, the sawfish-like ray Texatrygon, the eagle ray Pseudohypolophus, the hybodont shark Hybodus (Fiorillo 1999, page 261; note that this classification may be incorrect), the orectolobiform shark Cretorectolobus (Kirkland et al 2016, page 160), the 10 foot long sand tiger shark Carcharias amonensis (Sprinkel et al 2012, page 12; “Carcharias amonensis”), the enormous 20 foot long sand tiger Leptostyrax, and two unidentified species of pycnodont fish (Fiorillo 1999, pages 261-262). The Mowry Sea was also home to numerous species of marine reptiles during that time, including the 6 foot long sea turtle Desmatochelys lowii (Williston 1894, pages 5-18), the 18 foot long ichthyosaur Platypterygius americanus (Nace 1939, pages 673-686; McGowan 1972, pages 9-29), the 15 foot long pliosaur Brachauchenius lucasi (Williston 1903, pages 57-67), the 12 foot long polycotylid plesiosaurs Eopolycotylus rankini (Albright et al 2007, pages 47-52) and Trinacromerum bentonianum (Cragin 1888 pages 404-407; Cragin 1891, pages 171-174; Albright et al 2007, page 52), and the giant 38 foot long elasmosaurid plesiosaur Thalassomedon haningtoni (Welles 1943, pages 125-254; Sachs et al 2016, pages 38-40). Another marine reptile which possibly inhabited this prehistoric sea was the primitive mosasaur Sarabosaurus, which is known to have lived 94 MYA.

Post-Script

If you enjoy these drawings and articles, please click the “like” button, and leave a comment to let me know what you think. Subscribe to this blog if you wish to be immediately informed whenever a new post is published. Kindly check out my pages on Redbubble and Fine Art America if you want to purchase merch of my artwork. Also, please consider becoming a patron on my Patreon page so that I can afford to purchase the art supplies and research materials that I need to keep posting art and articles onto this website. And, as always, keep your pencils sharp.

Bibliography

Books

Cook, George H. Geology of New Jersey. Newark: The Dailey Advertiser, 1868.

Haworth, Erasmus. Geological Survey of Kanas, Volume 2. Topeka: The Kansas State Printing Company, 1897.

https://books.google.com/books?id=pdo6AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Schwimmer, David R. King of the Crocodylians: The Paleobiology of Deinosuchus. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002.

Articles

Adams, Thomas L.; Polcyn, Michael J.; Mateus, Octávio; Winkler, Dale A.; Jacobs, Louis L. (2011). “First occurrence of the long-snouted crocodyliform Terminonaris (Pholidosauridae) from the Woodbine Formation (Cenomanian) of Texas”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 31, issue 3 (May 1, 2011). Pages 712-716.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02724634.2011.572938.

Albright III, L. Barry; Gillette, David D.; Titus, Alan L. (2007). “Plesiosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian-Turonian) Tropic Shale of southern Utah, part 2: Polycotylidae”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 27, issue 1 (March 2007). Pages 41-58.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/40662737_Plesiosaurs_from_the_Upper_Cretaceous_Cenomanian-Turonian_Tropic_Shale_of_southern_Utah_part_2_Polycotylidae.

Apesteguía, Sebastián; Smith, Nathan D.; Juárez Valieri, Rubén; Makovicky, Peter J. (2016). “An Unusual New Theropod with a Didactyl Manus from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina”. PLOS ONE, volume 11, issue 7: e0157793 (July 13, 2016).

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0157793.

Avrahami, Haviv M.; Gates, Terry A.; Heckert, Andrew B.; Makovicky, Peter J.; Zanno, Lindsay E. (2018). “A new microvertebrate assemblage from the Mussentuchit Member, Cedar Mountain Formation: insights into the paleobiodiversity and paleobiogeography of early Late Cretaceous ecosystems in western North America”. PeerJ, volume 6: e5883 (November 16, 2018).

https://peerj.com/articles/5883/.

Avrahami, Haviv M.; Makovicky, Peter J.; Zanno, Lindsay E. (2023). “An Exceptional Assemblage of New Orodromine Dinosaurs from the Poorly Characterized Mid-Cretaceous of North America”. The Anatomical Record, volume 306, issue S1 – Special Issue: 14th Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems and Biota, Salt Lake City, Utah (June 8-10, 2023). Pages 3-267.

https://anatomypubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ar.25219?fbclid=IwAR0_xo_XZ2YhY2aHj4k7wU7vkVp5YF8oixE5gIOMzhWIWfNxwVA-SQPsU7I.

Avrahami, Haviv M.; Mackovicky, Peter J.; Tucker, Ryan T.; Zanno, Lindsay E. (2024). “A new semi-fossorial thescelosaurine dinosaur from the Cenomanian-age Mussentuchit Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation, Utah”. The Anatomical Record: e25505 (July 9, 2024).

https://anatomypubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ar.25505.

Avrahami, Haviv M.; Zanno, Lindsay E.; Mackovicky, Peter J. (2019). “Paleohistology of a new orodromine from the Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian) Mussentuchit Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation, Utah; Histological implications for burrowing behavior”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology Program Abstracts, October 9-12, 2019). Pages 56-57.

https://vertpaleo.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/SVP-Program-book-v8_w-covers.pdf.

Bassler, R. S.; Berry, Edward Wilbur; Clark, William Bullock; Gardner, Julia A.; Pilsbry, Henry A.; Stephenson, Lloyd W. (1916). “Systematic Paleontology of the Upper Cretaceous Deposits of Maryland”. Maryland Geological Survey (1916). Pages 345-578.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Upper_Cretaceous/oBm8AAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Hyposaurus&pg=PA349&printsec=frontcover.

Benson, Roger B. J.; Carrano, Matthew T; Brusatte, Stephen L. (2010). “A new clade of archaic large-bodied predatory dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) that survived to the latest Mesozoic”. Naturwissenschaften, volume 97, issue 1. Pages 71-78.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272152523_A_new_clade_of_archaic_large-bodied_predatory_dinosaurs_Theropoda_Allosauroidea_that_survived_to_the_latest_Mesozoic.

Bergendahl, M. H.; Davis, R. E.; Izett, G. A. (1960). “Geology and Mineral Deposits of the Carlisle Quadrangle, Crook County, Wyoming”. U. S. Department of the Interior Geological Survey Bulletin 1082-I: Geology and Mineral Deposits of the St. Regis-Superior Area, Mineral County, Montana. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1960. Pages 613-706.

https://books.google.com/books?id=N6YPAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Bonde, Joshua W.; Varricchio, David J.; Jackson, Frankie J.; Loope, David B.; Shirk, Aubrey M. (2008). “Dinosaurs and dunes! Sedimentology and paleontology of the Mesozoic in the Valley of Fire State Park”. The Geological Society of America Field Guide 11: Field Guide to Plutons, Volcanoes, Faults, Reefs, Dinosaurs, and Possible Glaciation in Selected Areas of Arizona, California, and Nevada (2008). Pages 249-262.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275524211_Dinosaurs_and_dunes_Sedimentology_and_paleontology_of_the_Mesozoic_in_the_Valley_of_Fire_State_Park.

Brikiatis, Leonidas (2016). “Late Mesozoic North Atlantic land bridges”. Earth-Science Reviews, volume 159 (May 2016). Pages 47-57.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0012825216300794.

Buffetaut, Eric (1976). “Une novelle definition de la famile de Dyrosauridae De Stefano, 1903 (Crocodilia, Mesosuchia) et ses consequenses: Inclusion des genres Hyposaurus et Sokotosuchus dans les Dyrosauridae”. Geobios, volume 9 (1976). Pages 333-336.

Carpenter, Kenneth; Bartlett, Jeff; Bird, John; Barrick, Reese (2008). “Ankylosaurs from the Price River Quarries, Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous), east-central Utah”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 28, issue 4 (December 12, 2008). Pages 1,089-1,101.

Carpenter, Kenneth; Cifelli, Richard (2016). “A possible juvenile ceratopsoid ilium from the Cenomanian of central Utah, U.S.A.”. Cretaceous Research, volume 60 (May 2016). Pages 167-175.

Carpenter, Kenneth; Kirkland, James I. (1998). “Review of Lower and Middle Cretaceous Ankylosaurs from North America”. In Lucas, S. G.; Kirkland, J. I.; Estep, J. W., eds. Lower and Middle Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 14. Pages 249-270.

https://books.google.com/books?id=yF4fCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA249#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Carpenter, Kenneth; Kirkland, James I.; Burge, Donald L.; Bird, John (1999). “Ankylosaurs (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) of the Cedar Mountain Formation, Utah, and their stratigraphic distribution”. In: Gillette, David, ed. Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah. Utah Geological Survey Miscellaneous Publication 99-1. Pages 243-251.

Chinnery, Brenda J.; Lipka, Thomas R.; Kirkland, James I.; Parrish, J. Michael; Brett-Surman, Michael K. (1998). “Neoceratopsian teeth from the Lower to Middle Cretaceous of North America”. In Lucas, S. G.; Kirkland, J. I.; Estep, J. W., eds. Lower to Middle Cretaceous Non-Marine Cretaceous Faunas. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 14. Pages 297-302.

https://books.google.com/books?id=yF4fCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA249#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Cifelli, Richard L.; Kirkland, James I.; Weil, Anne; Deinos, Alan L.; Kowallis, Bart J. (1997). “High-precision 40Ar/39Ar geochronology and the advent of North America’s Late Cretaceous terrestrial fauna”. Proceedings National Academy of Science USA, volume 94, issue 21 (October 14, 1997). Pages 11,163-11,167.

https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.94.21.11163.

Cifelli, Richard L.; Nydam, Randall L.; Gardner, James D.; Weil, Anne; Eaton, Jeffrey G., Kirkland, James I.; Madsen, Scott K. (1999). “Medial Cretaceous vertebrates from the Cedar Mountain Formation, Emery County, the Mussentuchit local fauna”. In Gillette, David, ed. Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah. Utah Geological Survey Miscellaneous Publication 99-1 (1999). Pages 219-242.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Vertebrate_Paleontology_in_Utah/qeRM16ndBx4C?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Polydectes+Goniopholididae&pg=PA225&printsec=frontcover.

Cobban, William A.; Kennedy, W. J. (1989). “The Ammonite Metengonoceras Hyatt, 1903, from the Mowry Shale (Cretaceous) of Montana and Wyoming”. U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1787-L. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1989. Pages 1-11.

https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/1787l/report.pdf.

Cockerell, T. D. A. (1919). “Some American Cretaceous Fish Scales, with Notes on the Classification and Distribution of Cretaceous Fishes”. U. S. Geological Survey. Shorter Contributions to General Geology, professional paper 120. Pages 165-203.

https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/0120i/report.pdf.

Condon, Steven M. (2000). “Stratigraphic Framework of Lower and Upper Cretaceous Rocks in Central and Eastern Montana”. U.S. Geological Survey Digital Data Series DDS-57 (2000). Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 2000. Pages 1-12.

https://pubs.usgs.gov/dds/dds-057/DDS57.pdf.

Cope, Edward D. (1868). “The Fossil Reptiles of New Jersey”. The American Naturalist, volume 1 (1868). Pages 23-30.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_American_Naturalist/tnM_AAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=Hyposaurus.

Cope, Edward D. (1869). “Minutes of the Meeting, December 21, 1869”. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, volume 21. Pages 191-192.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/30466#page/5/mode/1up.

Cope, Edward D. (1871). “Synopsis of the Extinct Batrachia and Reptilia of North America”. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, volume 14 (December 1871). Pages 1-252.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Transactions_of_the_American_Philosophic/iSlAt7zRUzUC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Hyposaurus&pg=PA80&printsec=frontcover.

Cope, Edward D. (1872). “On the Geology and Paleontology of the Cretaceous Strata of Kansas”. In Hayden, F. V., ed. Preliminary Report of the United States Geological Survey of Montana and Portions of the Adjacent Territories, Fifth Annual Report. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1872. Pages 318-349.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Annual_Report_of_the_United_States_Geolo/CokQI6qAv5YC?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=Hyposaurus.

Cope, Edward D. (1875). “The Vertebrata of the Cretaceous Formations of the West”. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1875.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/125656#page/11/mode/1up.

Cragin, F. W. (1888). “Preliminary description of a new or little known saurian from the Benton of Kansas”. American Geologist, volume 2. Pages 404-407.

https://books.google.com/books?id=QtzN3KkQxv0C&pg=PA404&lpg=PA404&dq=New+or+Little+Known+Saurian+from+the+Benton+of+Kansas&source=bl&ots=7KrQ2UbHcR&sig=kmfFpLZ8Qd5WZWK8IMCc9Sf7D9I&hl=en&sa=X&ei=OWs7U_ekH-mpsATFroC4Dw&ved=0CCcQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Cragin, F. W. (1891). “New observations on the genus Trinacromerum“. American Geologist, volume 8. Pages 171-174.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_American_Geologist/QO5LAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=1891+New+observations+on+the+genus+Trinacromerum&pg=PA171&printsec=frontcover.

Denton, Jr., Robert K.; Dobie, James L.; Parris, David C. (1997). “The Marine Crocodilian Hyposaurus in North America” In Callaway, Jack M.; Nichols, Elizabeth L., eds. Ancient Marine Reptiles. San Diego: Academic Press, 1997. Pages 375-398.

Elderbak, Khalifa; Leckie, R. Mark; Tibert, Neil E. (2014). “Paleoenvironmental and paleoceanographic changes across the Cenomanian-Turonian Boundary Event (Oceanic Anoxic Event 2) as indicated by foraminiferal assemblages from the eastern margin of the Cretaceous Western Interior Sea”. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, volume 413 (November 1, 2014). Pages 29-48.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280598264_Paleoceanography_and_paleoenvironmental_changes_of_the_CenomanianTuronian_boundary_interval_94-93_Ma_The_record_of_Oceanic_Anoxic_Event_2_in_the_Western_Interior_Sea.

Fiorillo, Anthony R. (1999). “Non-mammalian microvertebrate remains from the Robison Eggshell site, Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous), Emery County, Utah”. In Gillette, David D., ed. Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah. Utah Geological Survey Miscellaneous Publication 99-1. Pages 259-268.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Vertebrate_Paleontology_in_Utah/qeRM16ndBx4C?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Frederickson, Joseph A.; Cohen, Joshua E.; Hunt, Tyler C.; Cifelli, Richard L. (2017). “A new occurrence of Dakotasuchus kingi from the Late Cretaceous of Utah, USA, and the diagnostic utility of postcranial characters in Crocodyliformes”. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, volume 62, issue 2 (April 11, 2017). Pages 279-286.

https://www.app.pan.pl/archive/published/app62/app003382016.pdf.

Galton, Peter M.; Jensen, James A. (1975). “Hypsilophodon and Iguanodon from the Lower Cretaceous of North America”. Nature, volume 257 (October 23, 1975). Pages 668-669.

Galton, Peter Malcolm; Jensen, James A. (1979). “Remains of ornithopod dinosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous of North America”. Brigham Young University Geology Studies, volume 25, issue 3 (1979). Pages 1-10.

Hay, Oliver Perry (1902). “Bibliography and Catalogue of the Fossil Vertebrata of North America”. Bulletin of the United States Geological Survey, no. 179. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1902. Pages 1-868.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Bulletin_of_the_United_States_Geological/Q6QeAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Hyposaurus+vebbii+1872+cope&pg=PA516&printsec=frontcover.

Hedge, Josh; Zanno, Lindsay E. (2023). “Reassessing the Alpha-Taxonomy of the Oogenus Macroelongatoolithus Based on a New Test from the Cenomanian-Age Mussentuchit Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation (Utah)”. The Anatomical Record, volume 306, issue S1 – Special Issue: 14th Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems and Biota, Salt Lake City, Utah (June 8-10, 2023). Pages 3-267.

https://anatomypubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ar.25219?fbclid=IwAR0_xo_XZ2YhY2aHj4k7wU7vkVp5YF8oixE5gIOMzhWIWfNxwVA-SQPsU7I.

Huh, Min (2014). “First Record of a Complete Giant Theropod Egg Clutch from Upper Cretaceous Deposits, South Korea”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Program and Abstracts (November 2014). Page 151.

https://vertpaleo.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/SVP-2014-Program-and-Abstract-Book-10-14-2014.pdf.

Jeletzky, J. A. (1971). “Marine Cretaceous biotic provinces and paleogeography of western and Arctic Canada: Illustrated by a detailed study of ammonites”. Geological Survey of Canada, Paper 70-22, (January 27, 1971). Pages 1-92.

https://ftp.maps.canada.ca/pub/nrcan_rncan/publications/STPublications_PublicationsST/100/100663/pa_70_22.pdf.

Jensen, James A. (1970). “Fossil eggs in the Lower Cretaceous of Utah”. Brigham Young University Geological Studies, volume 17, issue 1 (May 1970). Pages 51-65.

https://geology.byu.edu/0000017c-e291-d5f3-a7fe-f2bd55530001/fossil-eggs-in-the-lower-cretaceous-of-utah-james-a-jensen-pdf.

Jones, Matthew M.; Petersen, Sierra V.; Curley, Allison N. (2022). “A tropically hot mid-Cretaceous North American Western Interior Seaway”. Geology, volume 50, issue 8 (May 9, 2022). Pages 954-958.

https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/geology/article-abstract/50/8/954/613546/A-tropically-hot-mid-Cretaceous-North-American?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

Kirkland, James I. (1998). “A new hadrosaurid from the upper Cedar Mountain Formation (Albian-Cenomanian: Cretaceous) of eastern Utah – the oldest known hadrosaurid (lambeosaurine?)”. In: Lucas, S. G.; Kirkland, J. I.; Estep, J. W., eds. Lower and Middle Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 14 (1998). Pages 283-295.

https://books.google.com/books?id=yF4fCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA249#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Kirkland, James I.; Britt, Brooks; Burge, Donald L.; Carpenter, Kenneth; Cifelli, Richard; Decourten, Frank; Eaton, Jeffrey; Hasiotis, Steve; Lawton, Tim (1997). “Lower to middle Cretaceous dinosaur faunas of the central Colorado Plateau: a key to understanding 35 million years of tectonics, sedimentology, evolution and biogeography”. Brigham Young University Geology Studies, volume 42, issue 2 (January 1997). Page 69-103.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259021967_Lower_to_middle_Cretaceous_dinosaur_faunas_of_the_central_Colorado_Plateau_a_key_to_understanding_35_million_years_of_tectonics_sedimentology_evolution_and_biogeography.

Kirkland, James I.; Cifelli, Richard L.; Britt, Brooks B.; Burge, Donald L.; DeCourten, Frank L.; Eaton, Jeffery G.; Parrish, J. Michael (1999). “Distribution of vertebrate faunas in the Cedar Mountain Formation, east-central Utah”. Miscellaneous Publication – Utah Geological Survey 99-1 (1999). Pages 201-217.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Vertebrate_Paleontology_in_Utah/qeRM16ndBx4C?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Kirkland, James I.; Suarez, Marina; Suarez, Celina; Hunt-Foster, ReBecca (2016). “The Lower Cretaceous in East-Central Utah—The Cedar Mountain Formation and its Bounding Strata”. Geology of the Intermountain West, volume 3 (October 2016). Pages 101-228.

https://giw.utahgeology.org/giw/index.php/GIW/article/view/11.

Krumenacker, L. J.; Zanno, Lindsay E.; Sues, Hans-Dieter (2022). “A partial tyrannosauroid femur from the mid-Cretaceous Wayan Formation of eastern Idaho, USA”. Journal of Paleontology, volume 96, issue 6 (December 20, 2022). Pages 1,336-1,345.

https://bioone.org/journals/journal-of-paleontology/volume-96/issue-6/jpa.2022.42/A-partial-tyrannosauroid-femur-from-the-mid-Cretaceous-Wayan-Formation/10.1017/jpa.2022.42.full.

Langston Jr., Wann (1995). “Dyrosaurs (Crocodilia, Mesosuchia) from the Paleocene Umm Himar Formation, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia”. In Whitmore Jr., Frank C.; Madden, Cary C., eds. Paleocene Vertebrates from Jabal Umm Himar, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2093. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1995. Pages F1-F36.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Paleocene_Vertebrates_from_Jabal_Umm_Him/NGH7PFzF3kwC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Hyposaurus+Dyrosauridae&pg=SL6-PA1&printsec=frontcover.

Leidy, Joseph (1865). “Cretaceous Reptiles of the United States”. Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, volume 14 (1865). Pages 1-135.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Introduction/ki5DAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Hyposaurus&pg=RA6-PA18&printsec=frontcover.

Makovicky, Peter J.; Cifelli, Richard; Zanno, Lindsay E. (2023). “The Mid-Cretaceous Fossil Record of Caenagnathids in North America and its Implications for the Timing of Faunal Interchange with Asia”. The Anatomical Record, volume 306, issue S1 – Special Issue: 14th Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems and Biota, Salt Lake City, Utah (June 8-10, 2023). Pages 3-267.

https://anatomypubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ar.25219?fbclid=IwAR0_xo_XZ2YhY2aHj4k7wU7vkVp5YF8oixE5gIOMzhWIWfNxwVA-SQPsU7I.

Makovicky, Peter J.; Shinya, Akiko; Zanno, Lindsay E. (2014). “New additions to the diversity of the Mussentuchit Member, Cedar Mountain Formation dinosaur fauna. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology Program and Abstracts, 2014. Page 175.

https://vertpaleo.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/SVP-2014-Program-and-Abstract-Book-10-14-2014.pdf.

Marsh, Othniel Charles (1877). “Notice of some new vertebrate fossils”. American Journal of Arts and Sciences, volume 14, issue 81 (September 1877). Pages 249-256.

http://marsh.dinodb.com/marsh/Marsh%201877%20-%20Notice%20of%20some%20new%20vertebrate%20fossils.pdf.

Maxwell, W. Desmond; Cifelli, Richard L. (2000). “Last evidence of sauropod dinosaurs (Saurischia: Sauropodomorpha) in the North American mid-Cretaceous”. Brigham Young University Geology Studies, volume 45 (January 2000). Pages 19-24.

https://geology.byu.edu/0000017d-0711-d1f8-a37f-6779c79a0001/geo-stud-vol-45-maxwell-cifelli-pdf.

McDonald, Andrew; Bird, John; Kirkland, James I.; Dodson, Peter (2012). “Osteology of the Basal Hadrosauroid Eolambia caroljonesa (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah”. PLOS ONE, volume 7, issue 10: e45712 (October 15, 2012).

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0045712.

McGowan, Christopher (1972). “The systematics of Cretaceous ichthyosaurs with particular reference to the material from North America”. Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming, volume 11, issue 1 (April 1, 1972). Pages 9-29.

Miller, Halsey W. (1967). “Cretaceous Vertebrates from Phoebus Landing, North Carolina”. Proceedings of The Academy of Natural Sciences, volume 119 (September 29, 1967). Pages 219-240.

https://books.google.com/books?id=ZuD4U_CkPV4C&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Molina-Perez, Rueben; Larramendi, Asier. Dinosaur Facts and Figures: The Theropods and other Dinosauriformes. Translated by David Connolly and Gonzalo Angel Ramirez Cruz. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019.

https://books.google.com/books?id=5m-KDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA54#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Mook, Charles C. (1925). “A Revision of the Mesozoic Crocodilia of North America”. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, volume 51 (1925). Pages 319-438.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Miocene_Oreodonts_in_the_American_Museum/RWGmuQBQt50C?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Hyposaurus+vebbii&pg=PA322&printsec=frontcover.

Nace, Raymond L. (1939). “A new ichthyosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Mowry Formation of Wyoming”. American Journal of Science, volume 237, issue 9 (1939). Pages 673-686.

https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-1939-r-07.pdf.

Naish, Darren; Cau, Andrea (2022). “The osteology and affinities of Eotyrannus lengi, a tyrannosauroid theropod from the Wealden Supergroup of southern England”. PeerJ, volume 10: e12727 (July 7, 2022).

https://peerj.com/articles/12727/.

Novas, F. E; Agnolín, F. L.; Ezcurra, M. D.; Canale, J. I.; Porfiri, J. D. (2012). “Megaraptorans as members of an unexpected evolutionary radiation of tyrant-reptiles in Gondwana”. Ameghiniana, volume 49, issue 4 abstracts supplement (2012). Page R33.

https://www.ameghiniana.org.ar/index.php/ameghiniana/article/view/868/1618.

Owen, Richard (1849). “Notes on Remains of Fossil Reptiles Discovered by Prof. Henry Rogers of Pennsylvania, U.S. in Greensand Formations of New Jersey”. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, volume 5 (January 31, 1849). Pages 380-383.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Quarterly_Journal_of_the_Geological/mtrAlEz1s2UC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Hyposaurus&pg=RA1-PA383&printsec=frontcover.

Porfiri, Juan D.; Novas, Fernando E.; Calvo, Jorge O.; Agnolín, Federico L.; Ezcurra, Martin D.; Cerda, Ignacio A. (2014). “Juvenile specimen of Megaraptor (Dinosauria, Theropoda) sheds light about tyrannosauroid radiation”. Cretaceous Research, volume 51 (2014). Pages 35-55.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263280059_Juvenile_specimen_of_Megaraptor_Dinosauria_Theropoda_sheds_light_about_tyrannosauroid_radiation.

Reeside Jr., John B.; Cobban, William A. (1960). “Studies of the Mowry Shale (Cretaceous) and Contemporary Formations in the United States and Canada”. Geological Survey Professional Paper 355. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1960. Pages 1-126.

https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/0355/report.pdf.

Renaut, Ray K.; Tucker, Ryan T.; King, M. Ryan; Crowley, James L.; Hyland, Ethan G.; Zanno, Lindsay E. (2023). “Timing of the Greenhorn transgression and OAE2 in Central Utah using CA-TIMS U-Pb zircon dating”. Cretaceous Research, volume 146 (2023).

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0195667122003287.

Robinson-Roberts, Laura N.; Kirschbaum, Mark A. (1995). “Paleogeography of the Late Cretaceous of the Western Interior of Middle North America–Coal Distribution and Sediment Accumulation”. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1561. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1995. Pages 1-115.

https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/1561/report.pdf.

Rolando, Alexis M. A.; Motta, Matias J.; Agnolín, Federico L.; Manabe, Makoto; Tsuihiji, Takanobu; Novas, Fernando E. (2022). “A large Megaraptoridae (Theropoda: Coelurosauria) from Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of Patagonia, Argentina”. Scientific Reports, volume 12, issue 1 (April 26, 2022): Article number 6318.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360214319_A_large_Megaraptoridae_Theropoda_Coelurosauria_from_Upper_Cretaceous_Maastrichtian_of_Patagonia_Argentina.

Sachs, Sven; Lindgren, Johan; Kear, Benjamin P. (2016). “Re-description of Thalassomedon haningtoni – an elasmosaurid from the Cenomanian of North America”. 5th Triennial Mosasaur Meeting: A global perspective on Mesozoic marine amniotes. Abstracts and Program (May 16-20, 2016). Pages 38-40.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303446624_Re-description_of_Thalassomedon_haningtoni_-_an_elasmosaurid_from_the_Cenomanian_of_North_America.

Simon, Danielle Jade (2014). “Giant Dinosaur (theropod) Eggs of the Oogenus Macroelongatoolithus (Elongatoolithidae) from Southeastern Idaho: Taxonomic, Paleobiogeographic, and Reproductive Implications”. M.S. thesis, Montana State University. Pages 1-110.

https://scholarworks.montana.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1/8693/SimonD0814.pdf.

Simon, D. J.; Varricchio, David J.; Jin, Xingsheng; Robison, Steven F. (2018). “Microstructural overlap of Macroelongatoolithus eggs from Asia and North America expands the occurrence of colossal oviraptorosaurs”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 38, issue 6 (November 2, 2018): e1553046.

Slattery, Joshua S.; Cobban, William A.; McKinney, Kevin C.; Harries, Peter J.; Sandness, Ashley L. (2013). “Early Cretaceous to Paleocene Paleogeography of the Western Interior Seaway: The Interaction of Eustasy and Tectonism”. Wyoming Geological Association, 68th Annual Field Conference (June 2013). Pages 22-60.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280641436_EARLY_CRETACEOUS_TO_PALEOCENE_PALEOGEOGRAPHY_OF_THE_WESTERN_INTERIOR_SEAWAY_THE_INTERACTION_OF_EUSTASY_AND_TECTONISM.

Sprinkel, Douglas A.; Madsen, Scott K.; Kirkland, James I.; Waanders, Gerald L.; Hunt, Gary J. (2012). “Cedar Mountain and Dakota Formations around Dinosaur National Monument: Evidence of the First Incursion of the Cretaceous Western Interior Sea into Utah”. Utah Geological Survey Special Study 143. Pages 1-20.

https://ugspub.nr.utah.gov/publications/special_studies/SS-143/SS-143.pdf.

Stewart J. D.; Hakel, Marjorie (2006). “Ichthyofauna of the Mowry Shale (Early Cenomanian) of Wyoming”. In New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 35. Late Cretaceous Vertebrates from the Western Interior. Spencer G. Lucas and Robert M. Sullivan, eds. Albuquerque: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, 2006. Pages 161-163.

Todd, J. E. (1911). “Is the Dakota Formation Upper or Lower Cretaceous?”. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science, volume 23-24 (January 1911). Pages 65-69.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3624565?seq=1.

Troxell, Edward Leffingwell (1925). “Hyposaurus, a Marine Crocodilian”. The American Journal of Science, series 5, volume 9, issue 54 (June 1925). Pages 489-514.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_American_Journal_of_Science/VNkCAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Hyposaurus&pg=PA489&printsec=frontcover.

Tsuihiji, Takanobu; Watabe, Mahito; Barsbold, Rinchen; Tsogtbaatar, Khishigjav (2015). “A gigantic caenagnathid oviraptorosaurian (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Gobi Desert, Mongolia”. Cretaceous Research, volume 56 (September-December 2015). Pages 60-65.

Wang, Hongshan (2002). “Diversity of angiosperm leaf megafossils from the Dakota Formation (Cenomanian, Cretaceous), north western interior, USA”. PhD dissertation, University of Florida (January 2002). Pages 1-394.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/34916342_Diversity_of_angiosperm_leaf_megafossils_from_the_Dakota_Formation_Cenomanian_Cretaceous_north_western_interior_USA.

Welles, Samuel Paul (1943). “Elasmosaurid plesiosaurs with description of new material from California and Colorado”. Memoirs of the University of California, volume 13 (1943). Pages 125-254.

Williston, S. W. (1894). “A New Turtle from the Benton Cretaceous”. Kansas University Quarterly, volume 3, issue 1 (July 1894). Pages 5-18.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/35118#page/25/mode/1up.

Williston, Samuel W. (1903). “North American Plesiosaurs, part 1”. Field Columbian Museum-Geology, volume 2, issue 1 (April 1903). Pages 1-77.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/21579#page/9/mode/1up.

Williston, S. W. (1905). “The Hallopus, Baptanodon, and Atlantosaurus Beds of Marsh”. The Journal of Geology, volume 13, issue 4 (May-June 1905). Pages 338-350.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/621233.

Williston, S. W. (1906). “American Amphicoelian Crocodiles”. The Journal of Geology, volume 14, issue 1 (January-February 1906). Pages 1-17.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2e/American_Amphicoelian_Crocodiles.pdf.

Xu, Xing; Tan, Qingwei; Wang, Jianmin; Zhao, Xijin; Tan, Lin (2007). “A gigantic bird-like dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of China”. Nature, volume 447, issue 7146 (June 14, 2007). Pages 844-847.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6272413_Gigantic_bird-like_dinosaur_from_the_Late_Cretaceous_of_China.

Zanno, Lindsay E.; Makovicky, Peter J. (2013). “Neovenatorid theropods are apex predators in the Late Cretaceous of North America”. Nature Communications, volume 4 (November 22, 2013): 2827.

https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms3827.

Zanno, Lindsay E.; Tucker, Ryan T.; Canoville, Aurore; Avrahami, Haviv M.; Gates, Terry A.; Makovicky, Peter J. (2019). “Diminutive fleet-footed tyrannosauroid narrows the 70-million-year gap in the North American fossil record”. Communications Biology, volume 2 (February 21, 2019). Pages 1-12.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-019-0308-7.

Zanno, Lindsay E.; Gates, Terry A.; Avrahami, Haviv M.; Tucker, Ryan T.; Makovicky, Peter J. (2023). “An early-diverging iguanodontian (Dinosauria: Rhabdodontomorpha) from the Late Cretaceous of North America”. PLOS One, volume 18, issue 6: e0286042 (June 7, 2023).

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0286042

Zanno, Lindsay E.; Tucker, Ryan T.; Suarez, Celina; Avrahami, Haviv M.; Herzog, Lisa; Hedge, Josh; Lund, Eric; Freimuth, William J.; Beguesse, Kyla; Makovicky, Peter J. (2023). “Paleobiodiversity of the Mussentuchit Member, Cedar Mountain Formation (Utah): New Discoveries Enhance and Contextualize an Exceptional Window into Mid-Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems”. The Anatomical Record, volume 306, issue S1 – Special Issue: 14th Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems and Biota, Salt Lake City, Utah (June 8-10, 2023). Pages 3-267.

https://anatomypubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ar.25219?fbclid=IwAR0_xo_XZ2YhY2aHj4k7wU7vkVp5YF8oixE5gIOMzhWIWfNxwVA-SQPsU7I.

Zelenitsky, Darla Karen; Carpenter, Kenneth; Currie, Philip J. (2000). “The first record of elongatoolithid theropod eggshell from North America: The Asian oogenus Macroelongatoolithus from the Lower Cretaceous of Utah”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 20, issue 1 (March 2000). Pages 130-138.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232664352_First_record_of_elongatoolithid_theropod_eggshell_from_North_America_The_Asian_oogenus_Macroelongatoolithus_from_the_Lower_Cretaceous_of_Utah.

Zittel, K. A. (1890). Handbuch der Palaeontologie. I. Abteilung Paleozoologie. III. Band. Vertebrata (Pisces, Amphibia, Reptilia, Aves) [Handbook of Paleontology. Division I. Paleozoology. Volume III. Vertebrata (Pisces, Amphibia, Reptilia, Aves)] (1890). Pages xii-900.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/124860#page/11/mode/1up.

Websites

Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life: Western Interior Seaway. “Carcharias amonensis”.

https://www.cretaceousatlas.org/species/carcharias-amonensis/.

Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life: Western Interior Seaway. “Neocardioceras juddii”. https://www.cretaceousatlas.org/species/neocardioceras-juddii/.

National Geographic. “New tiny tyrannosaur helps show how T. rex got big”, by Michael Greshko (February 21, 2019). https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/new-tiny-t-rex-relative-moros-fills-north-american-fossil-gap.

Smithsonian. “Polydectes biturgidus Cope, 1869”. https://www.si.edu/object/nmnhpaleobiology_3448902.

Untamed Science. “Scientists Discover a New Dinosaur! Siats”, by Haley Nelson (November 22, 2013). https://untamedscience.com/blog/siats-dinosaur/.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment