Happy New Year, everyone! All over the world on the first day of the year, there is drinking, feasting, and fireworks. This day also marks the last day of many people’s holiday vacations, and they are all in for having one last big blow-out before they have to sober up and go back to the office on January 2.

You might not be surprised to learn that the ancient Romans also partied hard on January 1. The first day of every month was known as the Kalends, from which we get the word “calendar”. While each of the monthly Kalends were cause for celebration, the Kalends of January in particular had a reputation for being especially wild and raucous.

The month of January is named after the Roman god Janus, the god of new beginnings – very appropriate for the beginning of the year. Janus is typically portrayed in ancient iconography as a man with a double face, one looking forwards and another looking backwards, representing looking back on the past and looking forward to the future.

Originally, the Roman year didn’t begin in January – at first, it began in March. March is named after Mars, the Roman god of war, and the father of the divine twins Romulus and Remus who would found the city of Rome in 753 BC. January was month #11 and February was month #12. That’s the reason why September, October, November, and December, whose names literally mean “month #7, month #8, month #9, and month #10, and called what they are. All government officials took office on the first day of the year, which would have been March 1.

This calendar served its purpose just fine when Rome was just a city-state in west-central Italy, and even when the fledgling Roman Republic had expanded to occupy much of the Italian Peninsula. However, this calendar proved to be increasingly problematic as the Roman Republic grew more and more in size. Roman politicians weren’t just government officials, they were also religious officiates and military commanders. Not only were provincial governors in charge of tending to the province’s administration, they were also in command over all military units stationed within their province. This could be an issue if the province that the governor was in charge of was far away. The beginning of the military campaigning season occurred on March 23 on the day known as the Tubilustrium, “the day of the trumpet”. If you are officially invested into your office on March 1, and you have to travel all the way to Spain or Turkey to take command, that doesn’t give you a lot of time to get everything in order. Quite simply, there just wasn’t enough time to get everything ready.

Therefore, in 153 BC, the government of the Roman Republic decided to do something drastic – they decided to change the calendar. January and February, which had previously been at the end of the Roman calendar, were now moved to the beginning of it. January and February, previously the eleventh and twelfth months, were now the first and second. Just like before, Romans government officials/commanders took office at the beginning of the year, but now that date was January 1 instead of March 1. This gave them two and two-thirds months to get everything ready for the upcoming military campaign season. This also resulted in September, October, November, and December, previously month #7, month #8, month #9, and month #10, now becoming month#9, month #10, month #11, and month #12. Yet for some reason, the Romans neglected to change the months’ names…which has caused people to scratch their heads in confusion ever since.

Just like in the modern day, the new year brought about a party atmosphere in ancient Rome. We don’t know all that much about what sort of activities occurred during the time of the Roman Republic and much of the Roman Empire’s history. In ancient Rome, the New Year’s celebrations were a multi-day affair, beginning on December 31. On New Year’s Eve, people visited family and friends and exchanged gifts. The gifts were called strenae, said to derive from the name of the Sabine goddess Strenia who had a shrine and a sacred grove at one end of the Via Sacra, “the Sacred Way”. Varro stated that offerings were brought every year up to the Arx, the central citadel in the heart of Rome (Marcus Terentius Varro, On the Latin Language, book 5, chapter 47). The 4th Century politician and orator Symmachus states that, in Rome’s ancient past, twigs from Strenia’s sacred grove were brought to the capital on January 1, which were then used to foresee what the new year had in store, although he doesn’t explain how (Quintus Aurelius Symmachus, Ten Books of Letters, book 10, letter #35). On January 1, the two Senatorial consuls each sacrificed a bull to Jupiter, the king of the Roman pantheon. During the time of the empire, January 1 was the date that the senators swore their annual oath of allegiance to the emperor (Fowler 1899, page 278; Harris 2011, page 11).

The most information which we have dates to the Late Antique period, from the 4th Century AD onwards. The most detailed description that we have of the activities which occurred during this day was written by a Greek scholar and rhetorician named Libanius of Antioch, who, despite living in the 4th Century AD when Christianity was taking a firmer hold, was a firm practitioner of paganism. On this day, he wrote, people decorated their doorways with laurel branches, feasting and banquets abounded, there was dancing, and singing, and general mirth, and slaves were treated with much more leniency and liberality than they were accustomed to. Horse breeders led their horses to the temple to ask the gods for victory in this year’s chariot races (Harris 2011, page 12).

Preparations for the Festivities, painted by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1866). The Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts, USA.

One topic that Libanius devotes a lot of attention to is the practice of “mumming” – going door-to-door wearing masks and costumes and expecting (or in some cases demanding) money, gifts, drinks, and other forms of hospitality. While mumming is something that is often associated with medieval and early modern Europe, the custom seems to have had its origins in Late Antiquity. Activities included wearing masks of gods and mythological figures, cross-dressing, and wearing animal skins, all of which were denounced by the early Christian Church. According to the early 5th Century cleric Asterius of Amasea, on New Year’s Day, revelers journeyed from house-to-house, taking special care to visit the homes of the rich and powerful, and made an incessant clamor outside of their doors and didn’t leave until money was thrown out to them. It seems to have been an unofficial requirement that at least one of the party had to dress up as a stag with antlers. Is this where the phrase “stag party” comes from? Naturally, the early Christian Church, being the utter kill-joys that they were, strenuously chastised their congregation for daring to have fun. Saint Augustine of Hippo urged his followers not to engage in games, feasting, drinking, dancing, and gift-giving, for doing so meant that they were in league with demons (Harris 2011, pages 13-18).

Interestingly, January 2 was a day that most people stayed home and no work was done…probably because they were too hung over from the previous day’s festivities! (Harris 2011, page 12).

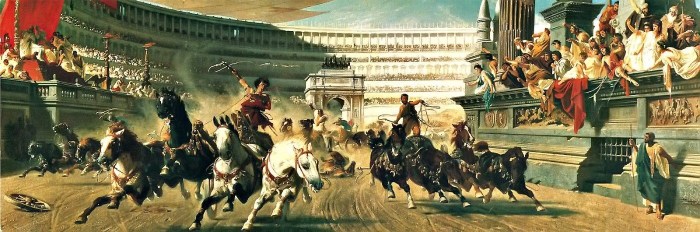

On January 3, a chariot race was held in the Hippodrome, the great racetrack in Constantinople (Harris 2011, page 12).

A Roman Chariot Race, by Alexander von Wagner (1882). Manchester City Art Galleries. Manchester, UK.

Also on January 3 and lasting got three days was the Compitalia street fair, celebrated in honor of the Lares Compitales, the guardian spirits of crossroads. There were four Compitaliae festivals during the year, one for each season – January 3-5 was the time of the winter Compitalia street fair.

But all parties have to come to an end eventually, and on January 6, everyone had to go back to work.

I truly enjoy writing my articles and drawing my art, but it’s increasingly clear that I can’t keep this up without your gracious financial assistance. Kindly check out my pages on Redbubble and Fine Art America if you want to purchase merch of my artwork. Consider buying my ancient Roman history books Four Days in September: The Battle of Teutoburg and The Great Illyrian Revolt if you or someone that you know loves that topic. Also, please consider becoming a patron on my Patreon page so that I can afford to purchase the art supplies and research materials that I need to keep posting art and articles onto this website.

Please check out the rest of my “Today in Ancient Rome” series for more articles on the ancient Roman calendar. You can find the whole list by clicking here!

Bibliography

Symmachus, Quintus Aurelius. Ten Books of Letters, book 10, letter #35.

https://la.wikisource.org/wiki/Libri_Decem_Epistolarum/X#EPIST._XXXV.

Varro, Marcus Terentius. On the Latin Language. Translated by Roland G. Kent. London: W. Heinemann, 1938.

https://archive.org/details/onlatinlanguage01varruoft/page/44/mode/2up.

Fowler, William Warde. The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic: An Introduction to the Study of the Religion of the Romans. London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd., 1899.

Harris, Max. Sacred Folly: A New History of the Feast of Fools. Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2011.

Categories: History, Uncategorized

Leave a comment