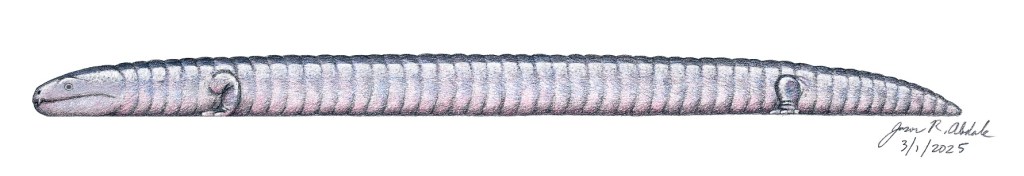

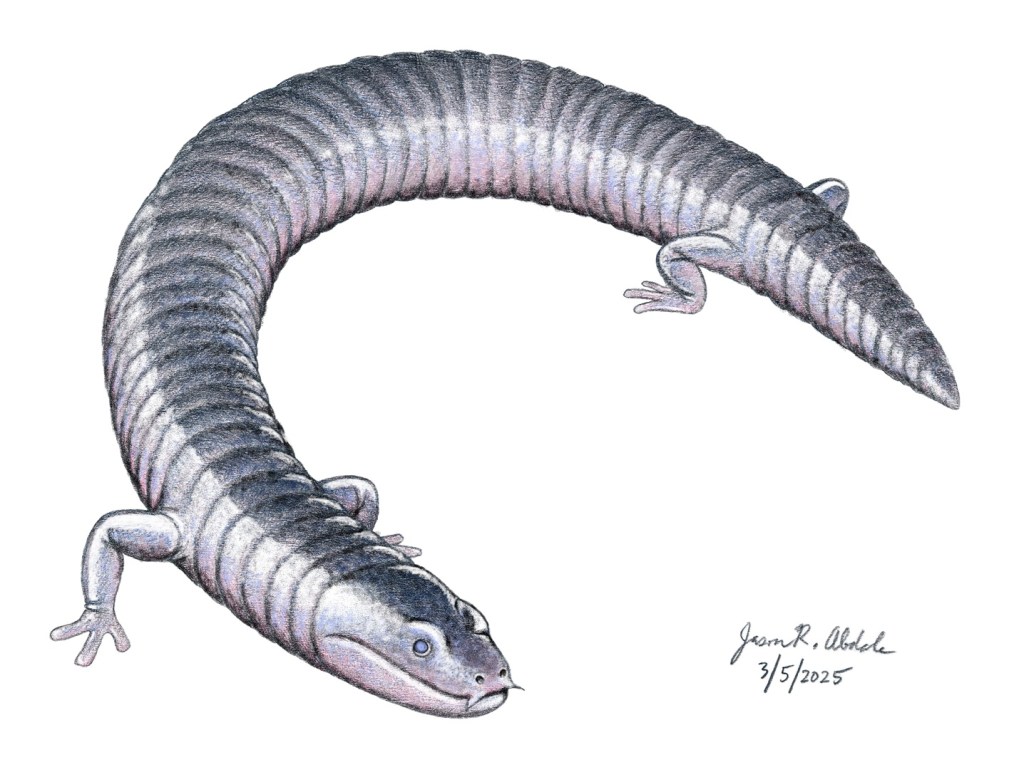

Eocaecilia was a 6 inch long worm-like amphibian which lived in Arizona during the early Jurassic Period 190 million years ago.

An astounding forty partial specimens have been uncovered of this animal, two of which are nearly-complete skulls, while the remainder of specimens consist of partial skulls and other fragmentary elements. All of them were collected from a single locality 300 meters away from Gold Spring, Coconino County, Arizona within the rocks of the Kayenta Formation, which dates to the early Jurassic Period about 195-180 million years ago. The skull exhibited features which were seen only in caecilians (Jenkins Jr. et al. 2007, pages 285, 288; Maddin et al. 2012: e50743). In 1993, this animal was named Eocaecilia micropodia. The genus name Eocaecilia means “dawn caecilian”. The species name micropodia means “tiny foot” (Jenkins Jr. and Walsh 1993, pages 246-250).

Caecilians are legless worm-like amphibians which live in underground burrows or moist undergrowth and leaf litter. There are over 200 species of caecilians alive today. They typically inhabit hot wet tropical environments, and are found in the jungles of Central and South America, Africa, India, and Southeast Asia. Most caecilians measure around 1-1.5 feet long. The smallest, the Seychelles Caecilian (Grandisonia brevis) from the Seychelles Islands, measures slightly over 4 inches long, while the largest, Thompson’s Caecilian (Caecilia thompsoni) from South America, measures 5 feet long (Nussbaum 1992, page 52).

Evidence suggests that caecilians evolved from salamanders or salamander-like amphibians, but it’s not entirely clear as to when this happened (Pardo et al. 2017). All modern caecilians are legless, but the early “stem caecilians” still retained two pairs of legs. The genus Funcusvermis, which lived in Arizona during the late Triassic Period 220 million years ago, is currently the oldest-known stem caecilian (Klingman et al. 2023, pages 102-107). It’s likely that the caecilian group branched off of Lissamphibia sometime during the Triassic or perhaps even the Permian Period. The most primitive caecilians alive today belong to the family Rhinatrematidae, which have skulls and other aspects of their body that are not as well-suitable for burrowing as their more advanced relatives (Nussbaum 1992, pages 54-55, 59).

Caecilians have very bad eyesight. Basically, their small eyes can only tell the difference between light and dark, and that’s it. That’s understandable, considering that caecilians are burrowing animals and spend much of their lives underground (Mohun et al. 2010; Mohun and Davies 2019). To compensate for their poor vision, all caecilians have a pair of sensory organs at the front of the mouth called “tentacles”. The name is a bit misleading, as they are nothing like the arms of cephalopods like octopus and squid. Sometimes they are just short stubby nubs, but other times they are elongated barbels (Nussbaum 1992, page 52).

Caecilians seem to feed mostly on earthworms, but their diets also include grubs, insects, and other tiny creatures. Some of the larger caecilians will even eat frogs and lizards (Nussbaum 1992, page 54). Despite their small size and their tiny teeth, caecilians have very strong bites. This is due to caecilians having a double-set of jaw-closing muscles instead of just a single set which all other terrestrial vertebrates possess (Nussbaum 1992, pages 52, 59; Kleinteich et al. 2008, pages 1,491-1,504).

To guard against predators, caecilians secrete toxic chemicals in their skin similar to how many toads and poison arrow frogs do. Most caecilians have dull earthy colors to help them blend into the dirt and leaf litter that they live in, but a few species have bright colors to warn potential predators of their foul taste (Nussbaum 1992, page 54). One South American caecilian species, Siphonops paulensis, secretes a poison which destroys red blood cells (Ferroni-Schwartz et al. 1998 pages 179-182). Did Eocaecilia also have poisonous glands within its skin? Possibly.

Unlike many other amphibians, all caecilians fertilize their eggs internally. Some species lay eggs, while other species give birth to live young. Caecilians also feed “milk” to their young, which is secreted from the oviducts (Nussbaum 1992, page 53). In particular, a study conducted in 2024 showed that the species Siphonops annulatus provides a calorie-rich milk rich in fats and carbohydrates to its young, enabling the hatchlings to grow quickly (Mailho-Fontana et al. 2024, pages 1,092-1,095). Did Eocaecilia also feed its young in such a way? Perhaps. Parental care, which is seen in many modern-day caecilians, helps to endure a viable population and might explain why we’ve found so many Eocacilia specimens in a small area. Evidently, these 6 inch long worm-like amphibians were quite common within the Kayenta Formation of prehistoric Arizona.

Eocaecilia micropodia. © Jason R. Abdale (March 1, 2025).

Eocaecilia micropodia. © Jason R. Abdale (March 5, 2025).

I truly enjoy writing my articles and drawing my art, but it’s increasingly clear that I can’t keep this up without your gracious financial assistance. Kindly check out my pages on Redbubble and Fine Art America if you want to purchase merch of my artwork. Consider buying my ancient Roman history books Four Days in September: The Battle of Teutoburg and The Great Illyrian Revolt if you or someone that you know loves that topic. Also, please consider becoming a patron on my Patreon page so that I can afford to purchase the art supplies and research materials that I need to keep posting art and articles onto this website.

Take care, and, as always, keep your pencils sharp.

Bibliography

Ferroni-Schwartz, Elisabeth N.; Schwartz, Carlos A.; Sebben, Antonio (1998). “Occurrence of hemolytic activity in the skin secretion of the caecilian Siphonops paulensis“. Natural Toxins, volume 6, issue 5 (September-October 1998). Pages 179-182.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/(SICI)1522-7189(199809/10)6:5%3C179::AID-NT20%3E3.0.CO;2-M.

Jenkins Jr., Farish A.; Walsh, Denis M. (1993). “An Early Jurassic caecilian with limbs”. Nature, volume 365, issue 6443 (September 16, 1993). Pages 246-250.

Jenkins Jr., Farish A.; Walsh, Denis M.; Carroll, Robert L. (2007). “Anatomy of Eocaecilia micropodia, a Limbed Caecilian of the Early Jurassic”. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, volume 158 issue 6 (August 1, 2007). Pages 285-365.

https://publications.mcz.harvard.edu/pubs/mczbull-158-6-285.pdf.

Kleinteich, Thomas; Haas, Alexander; Summers, Adam P. (2008). “Caecilian jaw-closing mechanics: Integrating two muscle systems”. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, volume 5, issue 29 (May 15, 2008). Pages 1,491-1,504.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2607354/.

Kligman, Ben T.; Gee, Bryan M.; Marsh, Adam D.; Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Smith, Matthew E.; Parker, William G.; Stocker, Michelle R. (2023). “Triassic stem caecilian supports dissorophoid origin of living amphibians”. Nature, volume 614, issue 7946 (January 25, 2023). Pages 102-107.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9892002/.

Maddin, Hillary C.; Jenkins Jr., Farish A.; Anderson, Jason S. (2012). “The Braincase of Eocaecilia micropodia (Lissamphibia, Gymnophiona) and the Origin of Caecilians”. PLoS ONE, volume 7 issue 12: e50743 (December 5, 2012).

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0050743.

Mailho-Fontana, Pedro L.; Antoniazzi, Marta M.; Coelho, Guilherme R.; Pimenta, Daniel C.; Fernandes, Ligia P.; Kupfer, Alexander; Brodie Jr., Edmund D.; Jared, Carlos (2024). “Milk provisioning in oviparous caecilian amphibians”. Science, volume 383, issue 6687 (March 8, 2024). Pages 1,092-1,095.

Mohun, Samantha Mila; Davies, Wayne Iwan Lee (2019). “The Evolution of Amphibian Photoreception”. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, volume 7 (August 26, 2019).

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/ecology-and-evolution/articles/10.3389/fevo.2019.00321/full.

Mohun, S. M.; Davies, W. L.; Bowmaker, J. K.; Pisani, D.; Himstedt, W.; Gower, D. J.; Hunt, D. M.; Wilkinson, M. (2010). “Identification and characterization of visual pigments in caecilians (Amphibia: Gymnophiona), an order of limbless vertebrates with rudimentary eyes”. The Journal of Experimental Biology, volume 213, issue 20 (October 15, 2010). Pages 3,586-3,592.

https://journals.biologists.com/jeb/article/213/20/3586/9820/Identification-and-characterization-of-visual.

Nussbaum, Ronald A. (1992). “Caecilians”. In Cogger, Harold G.; Zweifel, Richard G., eds. Reptiles & Amphibians. New York: Smithmark Publishers, 1992. Pages 52-59.

Pardo, Jason D.; Small, Bryan J.; Huttenlocker, Adam K. (2017). “Stem caecilian from the Triassic of Colorado sheds light on the origins of Lissamphibia”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), volume 114, issue 27 (June 19, 2017). Pages E5389-E5395

https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1706752114.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Thank you for posting this! Caecilians are fascinating animals, and your post had lots of info about them that was very interesting. I love learning about how animals reproduce and raise their young, so the concept of the mothers giving their young milk is absolutely fascinating!

I love your art style. It feels very reminiscent to the illustrations I remember from science textbooks and encyclopedias I had growing up. 🙂