Introduction

For paleontologists, determining whether fossils belong to an animal which is already known or if they belong to a hitherto undiscovered species can be a bit tricky, especially if the animal is only known from incomplete remains. Suppose you find two different body parts in two different locations – do they belong to two different species, or to the same species?

This is the question which centers around the plesiosaurs Colymbosaurus and Kimmerosaurus. Fossils of these two species of marine reptiles have been found in southern England within rocks dating to the late Jurassic Period approximately 150 million years ago. Colymbosaurus is known from numerous body fossils, but a head was never found. Kimmerosaurus is known three partial skulls and a few neck vertebrae, but the rest of the skeleton is missing. This leads to an interesting possibility – is it possible that Colymbosaurus and Kimmerosaurus are the same animal?

Colymbosaurus

The first fossil of Colymbosaurus which was discovered was a single humerus found in the 1830s within the Kimmeridge Clay Formation at Shotover Hill, Oxfordshire, England. This fossil was ascribed to the genus Plesiosaurus by the famous British anatomist and paleontologist Sir Richard Owen, and was named Plesiosaurus trochanterius (Owen 1840, pages 85-86). Afterwards, other fragmentary remains were uncovered in Dorset during the 1860s (Owen 1869, pages 1-12). In 1874, the British paleontologist Harry Seeley realized that these remains were different from those belonging to Plesiosaurus, and so he gave them a new name – Colymbosaurus, meaning “diving lizard” in ancient Greek (Seeley 1874, pages 445, 447-448).

In 1869, the British paleontologist Harry Seeley wrote of two fragmentary skeletons found within the Kimmeridge Clay Formation near the towns of Ely (collection ID code: CAMSM J.29596–29691, J.59736–59743) and Haddenham (collection ID code: CAMSM J.63919) in Cambridgeshire, England (Benson and Bowdler 2014, page 1,054). Both specimens are housed within Cambridge University’ Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences (CAMSM). Seeley declared that these belonged to a new species of Plesiosaurus called P. megadeirus (Seeley 1869, pages 97, 100-101, 121).

Then in 1874, Harry Seeley re-examined these plesiosaur specimens realized that these remains were different from those belonging to Plesiosaurus, and so he gave them a new name – Colymbosaurus, meaning “diving lizard” in ancient Greek. He gave the name Colymbosaurus trochanterius to the remains found in Oxfordshire, and the name Colymbosaurus megadeirus to the two specimens found in Cambridgeshire (Seeley 1874, pages 445, 447-448).

A survey of late Jurassic British plesiosaurs published in 1981 stated that fossils ascribed to Colymbosaurus have been found in the English counties of Dorset, Oxfordshire, Cambridgeshire, and Norfolk. These fossils date from the upper Kimmeridgian Stage to the upper Tithonian (also called Portlandian) Stage of the late Jurassic Period, approximately 152-145 MYA (Brown 1981, page 315; Imlay 1981, pages 12-13).

In 2014, Roger Benson and Timothy Bowdler stated that Colymbosaurus trochanterius is a nomen dubium, and referred the holotype specimen of that species to “Colymbosaurus sp.”. They then stated that Colymbosaurus megadeirus was the new type species for the genus Colymbosaurus. They also provided a new diagnosis for the genus Colymbosaurus, stating that the genus possessed the following features (Benson and Bowdler 2014, pages 1,053-1,054):

- Anteroposteriorly oriented ridge bisects the distal articular surfaces of the propodials.

- Propodials with a large posterodistal expansion bearing a postaxial ossicle facet of subequal size to the epipodial facets (currently only confirmed in C. svalbardensis).

- Cervical vertebrae are only slightly shorter anteroposteriorly than high dorsoventrally and lack a longitudinal ridge on their lateral surfaces, distinguishing Colymbosaurus from other penecontemporaneous plesiosauroids.

Benson and Bowdler also created the sub-family Colymbosaurinae of the family Cryptoclididae, which was created to include all genera which are more closely related to Colymbosaurus megadeirus than to Muraenosaurus leedsii or Cryptoclidus eurymerus. This sub-family presently includes Colymbosaurus, Abyssosaurus, Pantosaurus, Spitrasaurus, and Djupedalia. All members of the sub-family Colymbosaurinae possess the following features (Benson and Bowdler 2014, page 1,054):

- Hypophyseal ridge of atlas-axis complex does not extend, or does not extend far, onto ventral surface of the axis.

- Combined width of cervical zygapophyses distinctly narrower than the centrum (also present in Muraenosaurus and Picrocleidus, but absent in other cryptoclidids).

- Anteromedial process of the coracoid does not contact scapula.

- Anteromedial process of coracoid short and subtriangular.

- Anterior margin of radius is straight, almost straight, or convex.

In 2017, the official diagnosis for Colymbosaurus was amended yet again stating that the genus possessed the following anatomical features (Roberts et al. 2017: e1278381):

- Mid-cervical vertebrae marginally anteroposteriorly shorter than dorsoventrally tall and lacking a longitudinal ridge on the lateral surface.

- Middle caudal centra subrectangular due to a flat ventral surface, with widely spaced chevron facets.

- Propodials with a large posterodistal expansion at least twice as large as the preaxial expansion, bearing a single postaxial ossicle facet of subequal size to the epipodial facets.

- Ulna conspicuously anteroposteriorly wider than the radius and proximodistally short.

- Fibula symmetrically pentagonal in outline having equally long pre- and postaxial margins and with facets for the fibulare and astragalus subequal in length.

Although no skull of Colymbosaurus megadeirus has been found, the cumulative total of all fossils found so far give us a good idea of what the animal looked like overall. The animal had 41 neck vertebrae, 4 pectoral vertebrae, 17 dorsal vertebrae, and 3 sacral vertebrae; the number of tail vertebrae is unknown (Benson and Bowdler 2014, page 1,055). Due to the incompleteness of the remains, ascertaining Colymbosaurus’ total size is difficult. However, by doing a comparative analysis of the bones and comparing them with those of other well-known plesiosaurs, the majority of sources contend that Colymbosaurus measured 6 meters (20 feet) long or perhaps slightly longer (Brown 1981, pages 315, 317; Brown et al.1986, page 233; Miscellanea 1986, page 233; Dinosaurs and Other Fossil Reptiles of Europe 1993, page 14; Ellis 2003, page 136). Colymbosaurus was also apparently more heavily-built compared to its more well-known middle Jurassic relative Cryptoclidus (Brown et al.1986, page 233). In a way, this isn’t surprising, since Colymbosaurus was one-third bigger, and larger animals have more proportionally robust bones compared to smaller animals due to the increased weight and increased muscle mass needed to move the body.

In addition to fossils found in Europe, it’s possible that Colymbosaurus also lived along North America’s Pacific coast. In 1949, Professor J. W. Durham was leading his geology class on a field trip to Oakley Ranch in San Luis Obispo County, California when one of his students named Betty Olsonowski spotted two vertebrae embedded within a limestone boulder. Professor Durham suspected that this boulder had weathered out of the rock strata which formed the Franciscan Formation (also called the Franciscan Complex) which dates to the late Jurassic Period. These vertebrae were examined by Prof. Samuel P. Welles of the University of California, who identified them as a dorsal vertebra and sacral vertebra belonging to a plesiosaur – indeed, the first Jurassic plesiosaur to be found in the United States west of the Rocky Mountains – and the limestone was dated to the Tithonian Stage of the late Jurassic Period. In 1953, Welles ascribed the name Plesiosaurus hesternus, meaning “yesterday’s Plesiosaurus” (Wiktionary. “Hesternus”), to these two vertebrae (collection ID code: UCMP 41599). Based upon the size of the vertebrae, the animal which these backbones belonged to was clearly large. Unfortunately, both vertebrae were in a very weathered condition with only the centra remaining – all of the various bony processes had been broken off. Welles noted that the vertebrae did not possess any diagnostic features which could definitively identify it as belonging to a particular species, or even to a particular family. Nevertheless, he felt compelled to give these enigmatic bones a name anyway, stating “Since this is a new record, the specimen is named and described even though it cannot be demonstrated to differ from all previously known species” (Welles 1953, page 743). My, how things have changed since then! Paleontologists would never be able to get away with doing that sort of thing nowadays! Indeed, the name Plesiosaurus hesternus has since been relegated to being a nomen dubium (Storrs 1997, page 179). Welles stated that the vertebrae were most similar to those of Plesiosaurus trochanterius (which would later be renamed Colymbosaurus trochanterius) and also bore a certain similarity to Cryptoclidus oxoniensis (Welles 1953, pages 743-744). Could these vertebrae belong to Colymbosaurus? Maybe. They certainly date to the right time, and they seem big enough, but let’s not jump to conclusions. Because both Cryptoclidus and Colymbosaurus belong to the family Cryptoclididae, I think that we can take a chance and give these vertebrae the tentative identification of “Cryptoclididae sp. indet.” (meaning “from the family Cryptoclididae, species undetermined”), but assigning a more specific identification than this may be pushing things too far.

Kimmerosaurus

In 1967, Robert A. Langham Esquire discovered a fragmentary specimen at Endcombe Bay in Dorset, England consisting of a lower jaw, the back half of the upper jaw, an atlas-axis complex, and five anterior cervical vertebrae (collection ID code: BMNH R.8431). This specimen was situated within the Kimmeridge Clay Formation and dates to the upper Kimmeridgian Stage of the late Jurassic Period approximately 152-150 MYA. While the fossils were obviously similar in shape to the plesiosaur Cryptoclidus, these remains were distinct enough from it and other cryptoclidid genera to warrant its classification as a new genus. Therefore in 1981, David S. Brown officially named it Kimmerosaurus langhami, “Langham’s Kimmeridge lizard”, in honor of Mr. Robert Langham who found the specimen (Brown 1981, pages 253-254, 301-314; Brown et al. 1986, page 226; Fowles 1986, page 327; Krymholtz and Mesezhnikov 1988, page 53).

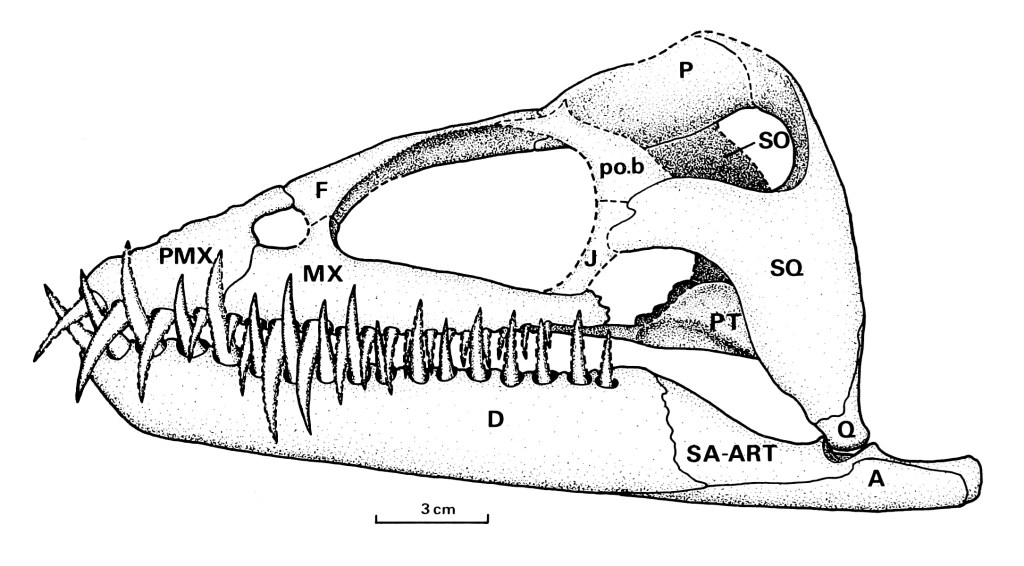

In-scale comparison of the skulls of Cryptoclidus eurymerus (top) and Kimmerosaurus langhami (bottom). Illustrations from Brown (1981), pages 259 and 304.

In 1976, Robert A. Langham’s son Peter, himself an avid fossil hound, collected a second specimen of Kimmerosaurus from the same locality as the holotype. Furthermore, like the holotype, this one too consisted of a braincase, the back half of the lower jaw, the atlas-axis complex, and five anterior cervical vertebrae. In September 1978, it was exhibited at an academic symposium at the University of Reading. Afterwards, it was given to the British Museum of Natural History where it was catalogued as BMNH R.10042, and in 1986, it was officially described as a new specimen of Kimmerosaurus. The size of the bones indicate that it was slightly larger as well as slightly more aged than the holotype (Brown 1981, page 304; Brown et al. 1986, pages 225-227, 230; Fowles 1986, page 327; Taylor 1986, pages 313-314).

A third fragmentary specimen consisting of pieces of the lower jaw along with fragments of the squamosals, quadrates, jugals, and post orbitals (collection ID code: BMNH R.1798) which had been sitting in the museum’s collections since 1890. The specimen had been discovered by one Robert Damon (1813-1889), and in 1890, it was gifted to the British Museum of Natural History. When this specimen was re-examined, it was discerned that this, too, belonged to Kimmerosaurus. This specimen had been found near Weymouth and also came from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation (Brown et al. 1986, pages 225-226, 228-229; Steward 1989, page 80; Taylor 1989, page 56).

David S. Brown commented on how similar the skull material of Kimmerosaurus was to Cryptoclidus. Since Cryptoclidus is commonly stated to have measured around 15 feet long, it’s plausible that Kimmerosaurus reached a similar size. Of course without a full skeleton, it’s impossible to know for sure.

Analysis

The only elements from both Colymbosaurus and Kimmerosaurus which were directly comparable were the anterior neck vertebrae, which were found to be similar to each other, but not exactly identical. Because of this, in 1986, David S. Brown, Angela C. Milner, and Michael A. Taylor put forward the idea that Colymbosaurus and Kimmerosaurus might be the same animal. Since Colymbosaurus was named first, this would mean that name would have priority. However, even the authors of that article were skeptical as to whether or not this might be the case, and stated that both names ought to be kept for the time being until more definitive evidence could be uncovered (Brown et al. 1986, pages 232-234).

In 2014, Roger Benson and Timothy Bowdler stated that Colymbosaurus and Kimmerosaurus were not the same due to numerous differences in the shape of the neck vertebrae between the two animals, especially noting that in Colymbosaurus, “The atlantal intercentrum forms the ventral portion of the atlantal cup, and bears the hypophyseal eminence on its ventral surface. Unlike in many other plesiosauroids, including some cryptoclidids…this structure does not form a ridge in CAMSM J.29598–29599. Instead, it forms a prominent, mammilate eminence, which extends anteroventrally…The posterior portion of the hypophyseal eminence of CAMSM J.29598–29599 extends posteriorly onto the ventral surface of the axial centrum as a weak convexity”, whereas in Kimmerosaurus, “the hypophyseal ridge extends further posteriorly, remaining prominent on the ventral surface of the axial centrum” (Benson and Bowdler 2014, pages 1,055-1,057). They also observed that the vertebrae of Kimmerosaurus were proportionally much shorter anteriorposteriorly than those belonging to Colymbosaurus. Furthermore, the cervical prezygapophyses on Colymbosaurus’s neck vertebrae are transversely narrow compared with the centrum, while in Kimmerosaurus, the cervical prezygapophyses are transversely broad (Benson and Bowdler 2014, page 1,059, 1,066-1,067). All of these anatomical differences in the structure of the neck vertebrae point to Colymbosaurus and Kimmerosaurus indeed being two distinct taxa.

Another point of contention is that the shape of Kimmerosaurus’ skull isn’t how you would expect it to look if it went with the skeleton of Colymbosaurus. As mentioned earlier, the bones of Colymbosaurus were much larger and more proportionally robust compared to those of its relative Cryptoclidus. If the skull of Kimmerosaurus really did belong with the skeleton of Colymbosaurus, you would therefore think that Kimmerosaurus’ skull would also be correspondingly beefy and heavily-built. However, the exact opposite is the case. Kimmerosaurus’ skull is actually much more slender and more lightly-built compared to the skull of Cryptoclidus, and also has many more teeth, and the teeth themselves are more slender and needle-like. It would be very out of character to have a massive plesiosaur with thick robust bones but then have a very delicately-built skull.

Another problem is phylogeny – the science of how different species are related to each other. Even if one believed that Colymbosaurus and Kimmerosaurus were two separate genera, there’s still the possibility that they could be closely related. However, this doesn’t appear to be the case. In 1981, David S. Brown stated that Colymbosaurus’ bones looked most similar to those of the 17 foot long plesiosaur Muraenosaurus. However, he also claimed that Kimmerosaurus’ skull was markedly dis-similar from that of Muraenosaurus in numerous respects, but appears to have been very similar to the skull of Cryptoclidus (Brown 1981, pages 305-313, 317-321). Later studies stated that Kimmerosaurus was actually most closely related to the 8 foot long short-necked plesiosaur Tatenectes from the mid-Jurassic Sundance Formation (O’Keefe and Wahl 2003, pages 52, 54, 57-58, 61; Street 2009, pages 3, 5-6; Massare et al. 2013, page 173; Roberts et al. 2017: e1278381; Roberts et al. 2020: e8652). If this analysis is true, then this dramatically changes how Kimmerosaurus would be reconstructed. It would be a short squat animal similar in shape to a seal, with a rather short neck and proportionally large flippers (O’Keefe et al. 2011, pages 330-339). Of course, the best way to clinch this would be to compare the skull material of Kimmerosaurus and Tatenectes to each other, but we only have fragments of Tatenectes’ skull (Street 2009, page14). We assume that Tatenectes had a short stumpy skull, as is seen in many modern artists’ reconstructions, because it would fit with its body shape, but did it? The truth is we don’t know. It’s possible that Tatenectes had a Cryptoclidus-esque skull on a distinctly un-Cryptoclidus-like body. Furthermore, I’d like to point out that we don’t have a complete neck for Tatenectes either, so we’re not positive that Tatenectes had a short neck – we just think that it did based upon the size of the few vertebrae we have found. Phylogenic analyses state that Cryptoclidus, Kimmerosaurus, and Tatenectes were closely related to each other (Roberts et al. 2017: e1278381; Roberts et al. 2020: e8652), and were likely far more visually similar to each other than we realize.

If anything, it’s likely that Colymbosaurus, not Kimmerosaurus, was the one which possessed an unusually-shaped skull. Phylogeny states that Colymbosaurus was much more closely related to the genera Tricleidus, Spitrasaurus, and Abyssosaurus than to Cryptoclidus (Knutsen et al. 2012, pages 175-186; Benson and Bowdler 2014, pages 1,054, 1,057, 1,066; Roberts et al. 2017: e1278381; Roberts et al. 2020: e8652). In fact, in 2012, the Norwegian species of Tricleidus, T. svalbardensis, which dates to the late Tithonian Stage about 146-145 MYA, was reclassified as another species of Colymbosaurus (Knutsen et al. 2012, pages 175-186; Rogov 2004, page 45). Colymbosaurus svalbardensis was diagnosed in 2017 as differing from C. megadeirus by possessing proximodistally shorter epipodials in the hind limb (tibia, fibula length/width ratio), a dorsoventrally taller neural canal on the mid-dorsal vertebrae (at least twice as tall as wide), a more gracile femoral shaft, and a posterior margin of the ischium that is abruptly squared-off and relatively broad (Roberts et al. 2017: e1278381). Both Tricleidus seeleyi and Abyssosaurus nataliae had shortened triangular skulls compared to the more elongate skulls of Cryptoclidus and Kimmerosaurus. Therefore, it would likely be most accurate if we reconstructed Colymbosaurus in a similar way.

Skull of Tricleidus seeleyi. Colymbosaurus likely had a similarly-shaped skull. Illustration from Brown (1981), page 296.

Conclusion

Based upon the evidence that we’ve examined, I believe the following:

- Colymbosaurus and Kimmerosaurus are two distinct genera and shouldn’t be merged together.

- Colymbosaurus had a large beefy body similar in shape to Muraenosaurus, and likely had a foreshortened skull similar in shape to Tricleidus.

- Kimmerosaurus would have closely resembled the plesiosaur Cryptoclidus, but with a more gracile skull.

- Prevailing reconstructions of the genus Tatenectes as a shortened stocky plesiosaur are incorrect and that it actually looked more similar to Cryptoclidus.

Both Colymbosaurus and Kimmerosaurus shared their late Jurassic marine world 150 MYA with many other marine reptiles including the gigantic 35 foot long pliosaur Pliosaurus (which was certainly the top predator in its ecosystem), the ichthyosaurs Brachypterygius, Nannopterygius, Grendelius, and Thalassodraco, the marine crocodylomorphs Cricosaurus, Dakosaurus, Bathysuchus, and Plesiosuchus, and even sea turtles such as Achelonia, Plesiochelys, and Thalassemys. Also dwelling below the waves of the Tethys Sea were numerous species of arthropods, mollusks, and fish.

If Colymbosaurus was related to creatures like Abyssosaurus and Tricleidus which are believed to have been deep-diving animals, then it’s likely that Colymbosaurus occupied a similar ecological niche and therefore lived out in the open ocean, diving to the depths in search of prey. If that’s the case, then Colymbosaurus was likely darkly colored, as many marine reptiles are suspected to be, spending a long time basking on the water’s surface to soak up as much heat as possible before diving, relying upon its ambient body temperature to keep it warm within the cold dark depths until it could come once again to the surface to breathe and warm up. By contrast, Kimmerosaurus was closely related to creatures like Cryptoclidus and Tatenectes which are believed to have inhabited shallow coastal waters. Therefore, it’s possible that Kimmerosaurus would have been colored lighter since there was more sunlight and the water was warmer. It’s even possible that Kimmerosaurus might have been camouflaged with stripes or blotches to mimic the shimmering rippling effects of light upon its body.

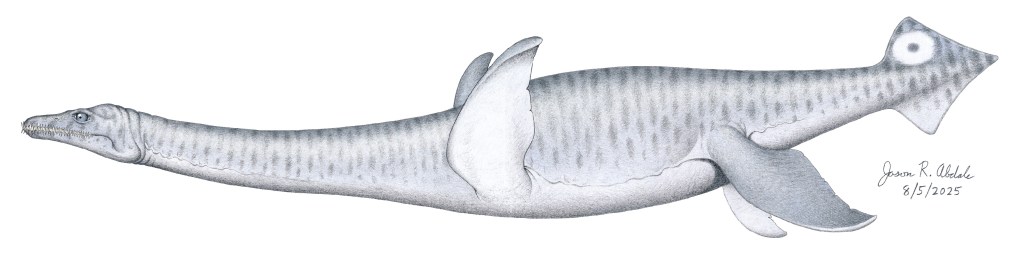

Hypothetical reconstruction of the 20 foot long plesiosaur Colymbosaurus megadeirus, dated from the upper Kimmeridgian to upper Tithonian Stages of the late Jurassic Period 152-145 MYA. The image is based upon the skeletal reconstruction of Muraenosaurus leedsi by Andrews (1910), the skull reconstruction of Muraenosaurus leedsi by Noè et al. (2017), and the skull reconstruction of Tricleidus seeleyi by Brown (1981). Image © Jason R. Abdale (August 6, 2025).

Hypothetical reconstruction of the 15 foot long plesiosaur Kimmerosaurus leedsi, dated to the upper Kimmeridgian Stage of the late Jurassic Period 152-150 MYA. The image is based upon the skeletal reconstruction of Cryptoclidus eurymerus by Brown (1981), the skeletal reconstruction of Tatenectes laramiensis by Street (2009) and O’Keefe et al. (2011), and the skull reconstruction of Kimmerosaurus leedsi by Brown (1981). Image © Jason R. Abdale (August 5, 2025).

I truly enjoy writing my articles and drawing my art, but it’s increasingly clear that I can’t keep this up without your gracious financial assistance. Kindly check out my pages on Redbubble and Fine Art America if you want to purchase merch of my artwork. Consider buying my ancient Roman history books Four Days in September: The Battle of Teutoburg and The Great Illyrian Revolt if you or someone that you know loves that topic, or my ancient Egyptian novel Servant of a Living God if you enjoy action and adventure.

Please consider becoming a patron on my Patreon page so that I can afford to purchase the art supplies and research materials that I need to keep posting art and articles onto this website. Professional art supplies are pricey, and many research articles are “pay to read”, and some academic journals are rather expensive. Patreon donations are just $1 per month – that’s it. If everyone gave just $1 per month, it would go a long way to purchase the stuff that I need to keep my blog “Dinosaurs and Barbarians” running.

Take care, and, as always, keep your pencils sharp.

Bibliography

Books

Miscellanea of the British Museum of Natural History I-II, volume 40, issue 5 (1986).

Andrews, Charles William. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Marine Reptiles of the Oxford Clay. Based on the Leeds Collection in the British Museum (Natural History), London, Part 1. London: The British Museum, 1910.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/125533#page/7/mode/1up.

Ellis, Richard. Sea Dragons: Predators of the Prehistoric Oceans. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003.

Seeley, Harry Govier. Index to the Fossil Remains of Aves, Ornithosauria, and Reptilia, from the Secondary System of Strata Arranged in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge. Cambridge: Deighton, Bell, and Co., 1869.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Index_to_the_Fossil_Remains_of_Aves_Orni/o-YGAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Articles

Dinosaurs and Other Fossil Reptiles of Europe. Second Georges Cuvier Symposium, Montbeliard (France), September 8-11, 1992.

Benson, Roger B. J.; Bowdler, Timothy (2014). “Anatomy of Colymbosaurus megadeirus (Reptilia, Plesiosauria) from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation of the U.K., and High Diversity among Late Jurassic Plesiosauroids”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 34, issue 5 (September 2014). Pages 1,053-1,071.

Brown, D. S. (1981). “The English Upper Jurassic Plesiosauroidea (Reptilia) and a review of the phylogeny and classification of the Plesiosauria”. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Geology, volume 35, issue 4 (December 17, 1981). Pages 253-347.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/33428283#page/277/mode/1up.

Brown, D. S.; Milner, A. C.; Taylor, M. A. (1986). “New material of the plesiosaur Kimmerosaurus langhami Brown from the Kimmeridge Clay of Dorset”. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Geology, volume 40, issue 5 (December 18, 1986). Pages 225-234.

https://ia600209.us.archive.org/21/items/biostor-118599/biostor-118599.pdf.

Fowles, John (1986). “Fossil Collection and Conservation in West Dorset”. The Geological Curator, volume 4, issue 6 (July 1986). Pages 325-329.

https://www.geocurator.org/images/resources/geocurator/vol4/geocurator_4_6.pdf.

Imlay, Ralph W. (1981). “Late Jurassic Ammonites from Alaska”. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1190. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1981. Pages 1-38.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Geological_Survey_Professional_Paper/K672BBO0tkYC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Titanites+giganteus+zone+Jurassic&pg=RA7-PA12&printsec=frontcover.

Knutsen, Espen M.; Druckenmiller, Patrick S.; Hurum, Jørn H. (2012). “Redescription and taxonomic clarification of ‘Tricleidus’ svalbardensis based on new material from the Agardhfjellet Formation (middle Volgian)”. Norwegian Journal of Geology, volume 92 (2012). Pages 175-186.

https://www.geologi.no/images/NJG_articles/NJG_2_3_2012_10_Knutsen_etal_Pr.pdf.

Krymholtz, G. Y.; Mesezhnikov, M. S. (1988). “The Jurassic Ammonite Zones of the Soviet Union”. Geological Society of America, Special Paper 223 (1988). Pages 1-116.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Jurassic_Ammonite_Zones_of_the_Sovie/pnE99ZoGcC4C?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Pavlovia+rotunda+zone+Jurassic&pg=PA53&printsec=frontcover.

Massare, Judy A.; Wahl, William R; Ross, Mike; Connely, Melissa V. (2013). “Palaeoecology of the marine reptiles of the Redwater Shale Member of the Sundance Formation (Jurassic) of central Wyoming, USA”. Geology Magazine, volume 151, issue 1 (July 2013). Pages 1-16.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272010903_Palaeoecology_of_the_marine_reptiles_of_the_Redwater_Shale_Member_of_the_Sundance_Formation_Jurassic_of_central_Wyoming_USA.

O’Keefe, Frank Robin; Street, Hallie P.; Wilhelm, Benjamin C.; Richards, Courtney D.; Zhu, Helen (2011). “A new skeleton of the cryptoclidid plesiosaur Tatenectes laramiensis reveals a novel body shape among plesiosaurs”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 31, issue 2 (2011). Pages 330-339.

https://mds.marshall.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1068&context=bio_sciences_faculty.

O’Keefe, Frank Robin; Wahl, William (2003). “Preliminary report on the osteology and relationships of a new aberrant cryptocleidoid plesiosaur from the Sundance Formation, Wyoming”. Paludicola, volume 4, issue 2 (July 2003). Pages 48-68.

https://mds.marshall.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1048&context=bio_sciences_faculty.

Owen, Richard (1840). “Report on British Fossil Reptiles”. Report of the Ninth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science; held at Birmingham in August 1839. Pages 43-126.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Report_of_the_Meeting_of_the_British_Ass/3fZcxnmKI0kC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=richard+owen+report+on+british+fossil+reptiles&pg=RA1-PA43&printsec=frontcover.

Owen, Richard (1869). “Monographs on the British Fossil Reptilia from the Kimmeridge Clay, No. III”. The Palaeontographical Society, volume 22, issue 98 (1869). Pages 1-12.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Monographs_on_the_British_Fossil_Reptili/LuTlBX4poI4C?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Roberts, Aubrey Jane; Druckenmiller, Patrick S.; Cordonnier, Benoit; Delsett, Lene L.; Hurum, Jørn H. (2020). “A new plesiosaurian from the Jurassic–Cretaceous transitional interval of the Slottsmøya Member (Volgian), with insights into the cranial anatomy of cryptoclidids using computed tomography”. PeerJ, volume 8: e8652 (March 31, 2020).

https://peerj.com/articles/8652/.

Roberts, Aubrey J.; Druckenmiller, Patrick S.; Delsett, Lene L.; Hurum, Jørn H. (2017). “Osteology and relationships of Colymbosaurus Seeley, 1874, based on new material of C. svalbardensis from the Slottsmøya Member, Agardhfjellet Formation of central Spitsbergen”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 37, issue 1 (January 1, 2017): e1278381.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02724634.2017.1278381.

Rogov, Mikhail (2004). “Ammonite-Based Correlation of the Lower and Middle (Panderi Zone) Volgian Substages with the Tithonian Stage”. Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation, volume 12, issue 7 (2004). Pages 35-57.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267949625_Ammonite-Based_Correlation_of_the_Lower_and_Middle_Panderi_Zone_Volgian_Substages_with_the_Tithonian_Stage.

Seeley, Harry G. (1874). “Note on some generic modifications of the plesiosaurian pectoral arch”. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, volume 30 (1874). Pages 436-449.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Quarterly_Journal_of_the_Geological/f1LzAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=1874+Seeley+Note+on+some+generic+modifications+of+the+plesiosaurian+pectoral+arch&pg=PA436&printsec=frontcover.

Steward, Donald I. (1989). “Lost and Found: Index to Volumes 1-4”. The Geological Curator, volume 5, issue 2 (January 1989). Pages 79-85.

https://www.geocurator.org/images/resources/geocurator/vol5/geocurator_5_2.pdf.

Storrs, Glenn W. (1997). “Morphological and Taxonomic Clarification of the Genus Plesiosaurus”. In Callaway, Jack M.; Nicholls Elizabeth L., eds. Ancient Marine Reptiles. San Diego: Academic Press, 1997. Pages 145-190.

Street, Hallie P. (2009). “A study of the morphology of Tatenectes laramiensis, a cryptocleidoid plesiosaur from the Sundance Formation (Wyoming, USA)”. Master of Science thesis, Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia (May 2009). Pages 1-46.

https://mds.marshall.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2084&context=etd.

Taylor, Michael A. (1986). “The Lyme Regis (Philpot) Museum: The History, Problems and Prospects of a Small Museum and its Geological Collection”. The Geological Curator, volume 4, issue 6 (July 1986). Pages 309-317.

https://www.geocurator.org/images/resources/geocurator/vol4/geocurator_4_6.pdf.

Taylor, Michael A. (1989). “‘Fine Fossils for Sale’: The Professional Collector and the Museum”. The Geological Curator, volume 5, issue 2 (January 1989). Pages 55-64.

https://www.geocurator.org/images/resources/geocurator/vol5/geocurator_5_2.pdf.

Welles, Samuel P. (1953). “Jurassic plesiosaur vertebrae from California”. Journal of Paleontology, volume 27, issue 5 (September 1953). Pages 743-744.

https://archive.org/details/sim_journal-of-paleontology_1953-09_27_5/page/743/mode/1up.

Websites

Wiktionary. “Hesternus”.

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/hesternus. Accessed on August 1, 2025.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment