Stegosaurus stenops. © Jason R. Abdale (August 1, 2020)

Stegosaurus is one of the most famous dinosaurs in the world. With its large back plates and spiked tail, it’s commonly seen in every child’s dinosaur book and is one of the few dinosaur names that most grown-ups can name off the tops of their heads. Yet Stegosaurus was just one of multiple members of the stegosaur family.

The stegosaurs arose during the middle of the Jurassic Period, and existed as one of the dominant dinosaur groups for several millions of years afterwards. Perhaps the most magnificent of all of them was the largest, Stegosaurus itself. Then, at the end of the Jurassic Period about 145 million years ago, all of the stegosaur species that were living within North America went extinct.

Or did they?

Our best fossils from North America which show what life was like during the early Cretaceous Period are found within the Cedar Mountain Formation, in rocks dated from 144 to 95 million years ago (MYA). So far, no fossils which have been positively identified as belonging to stegosaurs have been found within North America in rocks dated to the early Cretaceous. Within those rocks, all of the armored dinosaurs which have been found are ankylosaurians, mostly from the “polacanthine” sub-family, which includes creatures like Gastonia. These creatures arose during the late Jurassic Period, when the stegosaurs were having their hey-day, with creatures like Gargoyleosaurus and Mymoorapelta. It is suspected that the stegosaurs were pushed out by these newcomers who quickly took over as the dominant armored herbivores in the landscape.

However, that’s not entirely true. During the late Jurassic Period within the Morrison Formation, stegosaurs and the primitive ankylosaurians coexisted in the same environment for millions of years, so you can’t exactly say that the stegosaurs were promptly shoved aside as soon as the ankylosaurians showed up. Furthermore, it must be pointed out that the stegosaurs as a whole did not go completely extinct when the Jurassic Period came to an end. While Cretaceous stegosaurs have not yet been found within North America, they have been found elsewhere, in Europe, Africa, and Asia within rocks dated to the early Cretaceous Period, dating from around 145 to 120 MYA.

There are currently four genera of stegosaurs known from this time frame…

Paranthodon africanum, from South Africa (145-138 MYA) (collection ID code: BMNH 47338). This was the first stegosaur fossil found anywhere in the world, found in 1845. It was originally thought to belong to an iguanodontid, then it was re-classified as an ankylosaur, and finally as a stegosaur in 1929. Only the middle portion of the upper jaw was discovered, but it shows that its head was similar in shape to that of Stegosaurus. An examination of the teeth shows that they were very similar to Kentrosaurus. It was possibly another species of Kentrosaurus, or maybe it evolved directly from Kentrosaurus. Based upon the size of the fragmentary upper jaw, and comparing it with the skulls of other stegosaurs, Paranthodon is estimated to have measured somewhere between 15 to 20 feet long. There were some other fossils which were discovered, consisting of pieces of leg bones, some vertebrae, and a few other fragments. These all likely belonged to Paranthodon, and they were put into storage in the Albany Museum in Grahamstown, South Africa, and were awaiting further examination. Unfortunately, these fossils were all destroyed when the museum caught fire. Today, the original partial upper jaw is the only piece that’s left (1).

Partial upper jaw of the South African stegosaur Paranthodon. Illustration by Tracy L. Ford. Image used with permission. Lessem, Don; Glut, Donald F. The Dinosaur Society Dinosaur Encyclopedia. New York: Random House, Inc., 1993. Page 358.

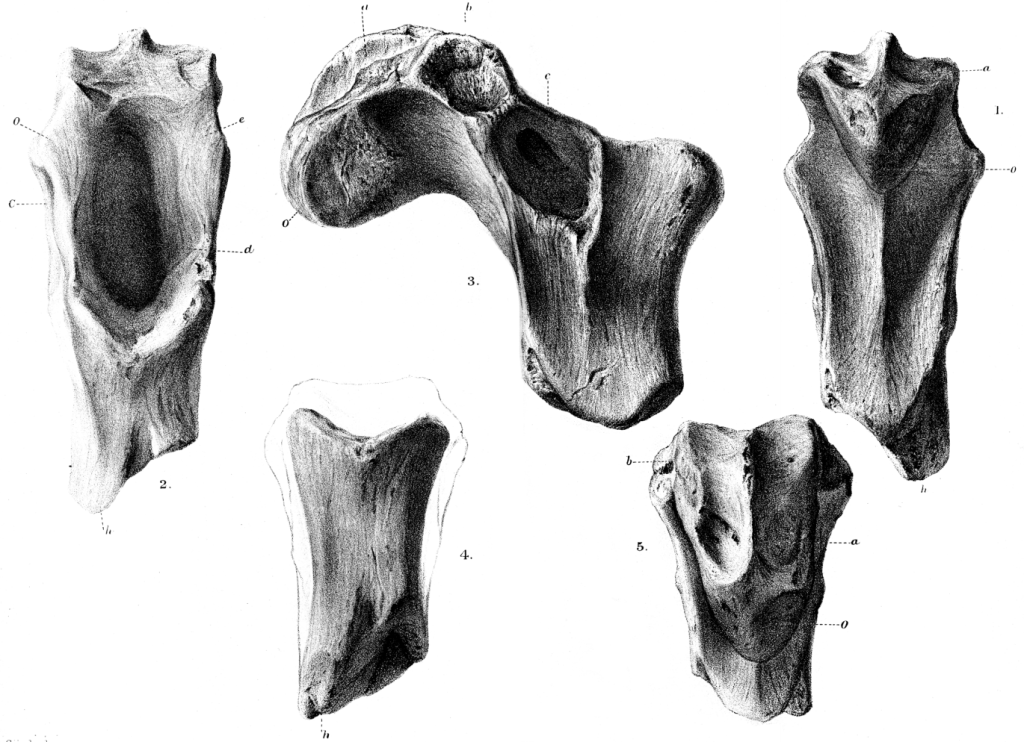

Regnosaurus northamptoni, from Tilgate Forest, from a quarry located north of the village of Cuckfield, West Sussex, England (131-119 MYA) (collection ID code: BMNH 2422). Known from only a fragment of the right side of the lower jaw, found in 1838 and described by Gideon Mantell in 1841. Due to its fragmentary nature, it has gone through numerous re-classifications including an iguanodont, an ankylosaurian, and finally as a camarasaurid sauropod. It wasn’t until 1993 that it was re-classified as a stegosaur (2).

Partial jawbone of Regnosaurus northamptoni. Note that this drawing is actually mirror-imaged. Public domain image, Wikimedia Commons.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Regnosaurus.jpg.

Craterosaurus pottonensis, from the “Potton Sands”, near the village of Potton, Bedfordshire, England (138-125 MYA) (collection ID code: SMC B.28814). Its remains consist of a single neural arch from a dorsal vertebra, described by Harry Seeley in 1874. Its size is unknown but one source places it at measuring around 13 feet long. Also, in 1983, a partial back plate and the base of a tail spine were found Lourinha, Estremadura Province, Portugal. Both of these were originally referred to the late Jurassic stegosaur genus Dacentrurus in 1991, but were then re-referred to Craterosaurus in 1994 when the rocks in which these fossils were found were identified as belonging to the early Cretaceous, not the late Jurassic. It is believed by some that Craterosaurus and Regnosaurus are the same animal, and since Regnosaurus was named first, then its name would have scientific priority (3).

Holotype specimen of Craterosaurus pottonensis, consisting of a partial neural arch from a vertebra. Public domain image, Wikimedia Commons.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Craterosaurus.png.

A hypothetical drawing of Regnosaurus, based upon Kentrosaurus, Lexovisaurus, and Dacentrurus. © Jason R. Abdale (May 30, 2022)

Wuerhosaurus homheni, found near Wuerho, Xinjiang Province, China (135-120 MYA). It was named in 1973. While Paranthodon, Regnosaurus, and Craterosaurus are known only from a single fragmentary piece, Wuerhosaurus is known from two partial skeletons. It was also substantially larger than the other three animals as well – estimates range widely from 15 to 25 feet long, making it almost as big or perhaps just as big as Stegosaurus. However, unlike Stegosaurus with its tall diamond-shaped plates, Wuerhosaurus‘ plates were short and stumpy (4).

Wuerhosaurus homheni. © Jason R. Abdale (August 11, 2022).

Evidence that stegosaurs lived during the early Cretaceous has also been found in Argentina, Spain, India, and Australia. However, the evidence that these remains belonged to stegosaurs is very slim, and it’s possible that these fossils have been mis-identified (5).

Numerous scientific studies carried out during the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s assert that western Europe was connected to the northern part of North America during the late Jurassic and early Cretaceous Periods via a trans-Atlantic land bridge. Leonidas Brikiatis states that it wasn’t until 129 MYA, during the time of the Cedar Mountain Formation’s Poison Strip Member, that the Atlantic Ocean expanded to such an extent that North America was at last permanently severed from Europe (6). This means that for a period of eleven million years, North America and Europe were directly connected to each other, allowing animals from one continent to travel to the other. The scientific term for this is “faunal interchange”. Evidence for this consists of animals which are traditionally associated with Europe such as megalosaur theropods, turiasaurian sauropods, and iguanodont ornithopods also being found within North America. If faunal interchange could occur one way, then it’s certainly plausible that it could go the other way as well.

Considering that there was faunal similarity between North America and Europe during the early Cretaceous Period, and since a land bridge connected North America and Europe during this time, and since stegosaurs are known to have lived in Europe during this time, then it is hypothetically possible for stegosaur remains to be discovered within North America in rocks dated to the early Cretaceous Period. This means that there might…there just MIGHT…be an as-yet-undiscovered Cretaceous stegosaur lying within the rocks of the Cedar Mountain Formation.

You might catch one or two obscure references on the internet or in old scientific articles that Cretaceous stegosaurs have already been found in North America, but first appearances can be deceiving. In 1898, the American geologist Nelson Horatio Darton had been prospecting at a place called Calico Canyon, located near the town of Buffalo Gap, Custer County, South Dakota when he spotted some fossil bones. They had been found within the earliest layers of Cretaceous rock in South Dakota, in the layer known as either the “Lakota Sandstone” or “Lakota Formation”. Darton initially believed that he had found the partial remains of a stegosaur, and it was described as such by the paleontologist Frederic A. Lucas shortly afterwards, calling it Stegosaurus marshi in honor of the famous (or infamous) paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh. However, Lucas quickly began to have second thoughts about this classification, and the following year he re-examined the fossils, and determined that they didn’t belong to Stegosaurus or to any stegosaur at all, but instead belonged to a nodosaurid ankylosaurian similar to the European armored dinosaur Polacanthus. Because of this, he re-named the animal Hoplitosaurus, “armored lizard” in 1902. Both the name and the classification have stuck ever since. The specimen is currently housed within the Smithsonian Institution (collection ID code: USNM 4752 (7).

So where does that leave us? Well, as stated before, it is hypothetically possible for European stegosaurs to have migrated across the trans-Atlantic land bridge into North America. However, no early Cretaceous stegosaurus have been discovered so far. As to whether or not any will be discovered, only time will tell. Get out there and start digging.

Source Citations

- Lessem, Don; Glut Donald F. The Dinosaur Society Dinosaur Encyclopedia. New York: Random House, Inc., 1993. Page 358; Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmolska, Halszka. The Dinosauria, 2nd Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. Pages 346, 348; Debus, Allen A. Prehistoric Monsters: The Real and Imagined Creatures of the Past that we Love to Fear. Jefferson: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2010. Pages 127-128, 292; Chinsamy-Turan, Anusuya. Famous Dinosaurs of Africa. Cape Town: Penguin Random House South Africa, 2013. Page 46.

- Lessem, Don; Glut Donald F. The Dinosaur Society Dinosaur Encyclopedia. New York: Random House, Inc., 1993. Page 400; Debus, Allen A. Prehistoric Monsters: The Real and Imagined Creatures of the Past that we Love to Fear. Jefferson: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2010. Pages 128-129, 293; Blows, William T. (1998). “A review of lower and middle Cretaceous dinosaurs from England” In Lucas, Spencer G.; Kirkland, James I.; Estep, John W., eds., Lower and Middle Cretaceous Ecosystems. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, bulletin 14 (1998). Page 33; Paleofile. “Regnosaurus”.

- Lessem, Don; Glut Donald F. The Dinosaur Society Dinosaur Encyclopedia. New York: Random House, Inc., 1993. Page 130; Farlow, James O.; Brett-Surman, M. K., ed. The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997. Page 296; Paleofile. “Craterosaurus”; Paleofile. “Regnosaurus”.

- Lessem, Don; Glut Donald F. The Dinosaur Society Dinosaur Encyclopedia. New York: Random House, Inc., 1993. Page 517.

- Brett-Surman, M. K.; Holtz, Jr., Thomas R.; Farlow, James O. The Complete Dinosaur, Second Edition. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012. Page 488-490.

- Brikiatis, Leonidas (2016). “Late Mesozoic North Atlantic land bridges”. Earth-Science Reviews, volume 159 (May 2016). Pages 47-57; Kirkland, James I.; Suarez, Marina; Suarez, Celina; Hunt-Foster, ReBecca (2016). “The Lower Cretaceous in East-Central Utah—The Cedar Mountain Formation and its Bounding Strata”. Geology of the Intermountain West, volume 3 (October 2016). Pages 138, 154.

- Darton, Nelson Horatio (1904). “Comparison of the Stratigraphy of the Black Hills, Bighorn Mountains, and Rocky Mountain Front Range”. Geological Society of America Bulletin, volume 15 (1904). Page 389; Lucas, Frederic A. (1901). “A New Dinosaur, Stegosaurus marshi, from the Lower Cretaceous of South Dakota”. Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum, volume 23, issue 1224 (1901). Pages 591-592; Lucas, Frederic A. (1902). “Paleontological Notes – A new generic name for Stegosaurus marshi”. Science, volume 16, issue 402 (September 12, 1902). Page 435; Carpenter, Kenneth; Kirkland, James I. (1998). “Review of Lower and Middle Cretaceous Ankylosaurs from North America”. In Lucas, S.G.; Kirkland, James I.; Estep, J.W., eds. Lower and Middle Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 14. Pages 266-267; Equatorial Minnesota. “Hoplitosaurus”. https://equatorialminnesota.blogspot.com/2017/06/hoplitosaurus.html. Accessed on July 5, 2022.

Bibliography

Books

Brett-Surman, M. K.; Holtz, Jr., Thomas R.; Farlow, James O. The Complete Dinosaur, Second Edition. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012.

Chinsamy-Turan, Anusuya. Famous Dinosaurs of Africa. Cape Town: Penguin Random House South Africa, 2013.

Debus, Allen A. Prehistoric Monsters: The Real and Imagined Creatures of the Past that we Love to Fear. Jefferson: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2010.

Lessem, Don; Glut Donald F. The Dinosaur Society Dinosaur Encyclopedia. New York: Random House, Inc., 1993.

Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmolska, Halszka. The Dinosauria, 2nd Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Articles

Blows, William T. (1998). “A review of lower and middle Cretaceous dinosaurs from England” In Lucas, Spencer G.; Kirkland, James I.; Estep, John W., eds., Lower and Middle Cretaceous Ecosystems. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, bulletin 14 (1998). Pages 29-38.

Brikiatis, Leonidas (2016). “Late Mesozoic North Atlantic land bridges”. Earth-Science Reviews, volume 159 (May 2016). Pages 47-57.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0012825216300794.

Carpenter, Kenneth; Kirkland, James I. (1998). “Review of Lower and Middle Cretaceous Ankylosaurs from North America”. In Lucas, S.G.; Kirkland, James I.; Estep, J.W., eds. Lower and Middle Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 14. Pages 249-270.

https://books.google.com/books?id=yF4fCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA249#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Darton, Nelson Horatio (1904). “Comparison of the Stratigraphy of the Black Hills, Bighorn Mountains, and Rocky Mountain Front Range”. Geological Society of America Bulletin, volume 15 (1904). Pages 379-448.

https://archive.org/details/sim_geological-society-of-america-bulletin_1904_15.

Kirkland, James I.; Suarez, Marina; Suarez, Celina; Hunt-Foster, ReBecca (2016). “The Lower Cretaceous in East-Central Utah—The Cedar Mountain Formation and its Bounding Strata”. Geology of the Intermountain West, volume 3 (October 2016). Pages 101-228.

https://giw.utahgeology.org/giw/index.php/GIW/article/view/11.

Lucas, Frederic A. (1901). “A New Dinosaur, Stegosaurus marshi, from the Lower Cretaceous of South Dakota”. Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum, volume 23, issue 1224 (1901). Pages 591-592.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/7511709#page/657/mode/1up.

Lucas, Frederic A. (1902). “Paleontological Notes – A new generic name for Stegosaurus marshi”. Science, volume 16, issue 402 (September 12, 1902). Page 435.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/31257497#page/449/mode/1up.

Websites

Equatorial Minnesota. “Hoplitosaurus”. https://equatorialminnesota.blogspot.com/2017/06/hoplitosaurus.html. Accessed on July 5, 2022.

Paleofile. “Craterosaurus”. http://www.paleofile.com/Dinosaurs/Armor/Craterosaurus.asp. Accessed on May 4, 2022.

Paleofile. “Regnosaurus”. http://www.paleofile.com/Dinosaurs/Sauropoda/Armor/Regnosaurus.asp. Accessed on May 4, 2022.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment