And today’s topic which is sure to start an argument is…Are there three different species of Falcarius within the Yellow Cat Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation?

The basal therizinosaur Falcarius utahensis, which was officially named and described in 2005 (Kirkland et al 2005, pages 84-87), provides us with our clearest picture to date of the origins of the theropod clade Therizinosauria. Abundant fossils of this 4 meter (12-13 feet long) creature were uncovered at a site called Crystal Geyser Quarry, located in eastern Utah. This locality is found within rock layers of the lower part of the Yellow Cat Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation, which dates to the early Cretaceous Period approximately 139-136 million years ago (MYA). In particular, the rock strata of this locality are positioned at the base of the lower Yellow Cat Member, which would date these rocks to approximately 139 MYA. The Crystal Dinosaur Quarry, abbreviated to CDQ in some paleontology articles, covers about two acres in area and the bone-bearing layer on average measures a meter thick. In some places, there are over 100 bones or pieces of bones crammed into a single square cubic meter, which makes extracting and separating them very difficult. By 2007, over 2,000 bones had been uncovered from the locality, and nearly all of them belonged to Falcarius utahensis (Kirkland and Madsen 2007, page 64).

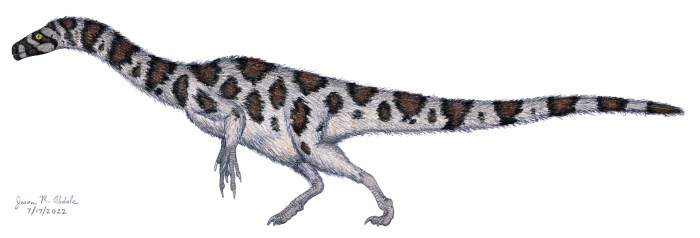

Falcarius utahensis. © Jason R. Abdale (July 17, 2022)

Afterwards, partial remains of another therizinosaur were uncovered at a place called Hayden-Corbett Quarry, named after Martha Hayden and Cari Corbett who discovered the locality. The rock strata of this locality are positioned within the upper Yellow Cat Member in rocks dated 135-132 MYA, and more specifically, within the base of the upper Yellow Cat Member (Kirkland et al 2016, page 119), which would date it to 135 MYA. In 2012, these fossils were classified as a new genus of therizinosaur named Martharaptor greenriverensis (Senter et al 2012: e43911). This therizinosaur was stated to have been more advanced than Falcarius and bore more of an affinity towards the Asian species Alxasaurus, which was larger and beefier than its North American counterpart. You would therefore not be unwarranted in thinking that the bones of Falcarius and Martharaptor would be dramatically different from one another. However, within the article which named and described Martharaptor, the number of anatomical differences separating this genus from Falcarius is very small, consisting of a slightly different shape to the manual claws and the foot’s fourth metatarsal. These differences do not seem to be sufficient to classify this animal as a new genus. This leads me to ask if Martharaptor is a separate genus, as is currently the case, or if it is just a different species of Falcarius – in which case, it would be re-named to “Falcarius greenriverensis”.

Martharaptor greenriverensis. © Jason R. Abdale (February 7, 2023). This illustration was made based upon claims presented within Senter et al (2012) that Martharaptor was more closely related to Alxasaurus than Falcarius, and it was therefore given a more Alxasaurus-ish appearance. However, even when I made this drawing, I had strong doubts as to whether this classification was accurate.

In order to answer this question, a thorough compare-and-contrast analysis must be made between the fossilized remains of these two animals. Yet this is easier said than done. Literally thousands of specimens consisting of either whole bones or fragments have been uncovered at Crystal Geyser Quarry belonging to Falcarius utahensis which are believed to have belonged to hundreds of individual animals. Unfortunately, due to the vast quantity of fossils which were uncovered, most of these specimens haven’t been prepared or analyzed yet. The work of preparing and examining these bones is slow careful pains-taking work which has already taken decades and the work still isn’t finished, and will likely not be finished for several decades more.

This problem is further compounded by the prospect that there might be two separate species of Falcarius within the lower Yellow Cat Member, not just one. According to Kirkland and Madsen (2007), “the Suarez sisters, in the process of conducting their research on the Crystal Geyser Quarry, discovered a second Falcarius bonebed about 0.5 mile to the west. This site is near the top of the lower Yellow Cat and is in part incorporated into the caprock (figure 37) indicating that it represents a completely separate mass-mortality event from the Crystal Geyser Quarry” (Kirkland and Madsen 2007, page 66). This locality was dubbed “the Suarez Site”, named after Celina and Marina Suarez who discovered it, and it was turned over to the College of Eastern Utah’s Prehistoric Museum (afterwards re-named to the Utah State University Eastern’s Prehistoric Museum) for excavation (Kirkland and Madsen 2007, page 63). Zanno et al (2014) elaborated on this by saying that the locality was 800 meters to the northwest of Crystal Geyser Quarry (Zanno et al 2014, page 260). The Suarez Site is situated right below the caprock dividing the lower and upper sub-units of the Yellow Cat Member, which would date the locality to 136 MYA, three million years younger than the Crystal Geyser Quarry.

In 2014, a short abstract was published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology which hinted that the therizinosaur remains from the Suarez Site which were originally identified as Falcarius in 2007 might not belong to that genus after all, or at least to the species F. utahensis. The specimens found at the Suarez Site, which may come from at least twenty-five individuals, seem to be more derived than F. utahensis and therefore might represent a second Falcarius species. According to Zanno et al (2014), “several attributes of the Suarez therizinosaurian indicate that it represents a more derived morphotype distinct from the variation observed in F. utahensis. In particular the more prominent development of the altiliac condition of the ilium, large distal boot of the pubis measuring more than half the pubic length, relatively straight and acuminate symphyseal aspect of the dentary, reduced recurvature of the dentary teeth, and marked ventral displacement of the mandibular condyle of the quadrate appear distinct” (Zanno et al 2014, page 260). However, no photographs or illustrations of these specimens were published, which makes it difficult to compare these specimens to those of Falcarius utahensis, or at least to those few specimens of F. utahensis which have been released from their plaster prisons.

In 2023 at the 14th Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems conference in Salt Lake City, Utah, an abstract was presented stating that the single fossil of Geminiraptor suarezarum, which was originally believed to belong to a troodontid raptor, may have actually belonged to the primitive therizinosaur which was found within the Suarez Site. This article stated “we hypothesize that Geminiraptor, as well as the remaining material from the SS, belong to a single therizinosaurian taxon” (Freimuth et al 2023). Within this same abstract, the subject of the intriguing “second therizinosaur” found at the Suarez Site also came up, and it stated the following: “A second bonebed ~1 km northwest of CGQ, the Suarez Site (SS), represents a second paucispecfic assemblage containing hundreds of therizinosaurian remains, potentially representing a distinct taxon… Differences in craniodental features suggest the SS therizinosaurian material may be taxonomically distinct from F. utahensis. These include a rostrocaudally longer, dorsoventrally lower maxillary profile in lateral view, a dorsoventrally short and elliptical maxillary fenestra, presence of a pneumatic excavation along the rostrodorsal margin of the maxillary fenestra, relatively straight symphyseal aspect of the dentary, reduced recurvature of the dentary teeth, and marked ventral displacement of the medial mandibular condyle of the quadrate” (Freimuth et al 2023).

All told, these are the distinguishing features of the therizinosaur from the Suarez Site, according to the two aforementioned sources:

- The maxilla bone in the upper jaw is both longer and taller compared to that seen in F. utahensis.

- The maxillary fenestra is dorso-ventrally short and elliptical in shape.

- There is a depression in the bone along the front edge of the maxillary fenestra.

- The medial mandibular condyle of the skull’s quadrate bone is positioned further ventrally than that seen in F. utahensis.

- The teeth within the dentary (the bone that forms the front half of the lower jaw) aren’t as curved as those teeth seen in F. utahensis.

- The symphysis (the front of the lower jaw where the left and right dentaries are joined together) is relatively straight.

- The ilium (the bone which forms the top of the pelvis) is shaped differently.

- The “pubic boot” at the base of the pubis is quite large, measuring over half of the total length of the pubis.

All of this raises the intriguing possibility that there might be three different species of Falcarius present throughout the span of the Yellow Cat Member, with the latter evolving directly from the former: Falcarius utahensis dated to 139 MYA, “Falcarius suarezarum” (unofficial name) dated to 136 MYA, and “Falcarius greenriverensis” (unofficial name) dated to 135 MYA. However, such a claim is greatly hampered from a lack of available specimens to compare with each other, so we are limited to examining those few specimens which are available as well as a critical reading of the scant descriptions which are given in scientific texts. Until more specimens are prepared, analyzed, described, and illustrated, this claim will have to remain as mere hypothetical speculation.

Sources

Kirkland, James I.; Zanno, Lindsay E.; Sampson, Scott D.; Clark, James M.; DeBlieux, Donald D. (2005). “A primitive therizinosauroid dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Utah”. Nature, volume 435 (2005). Pages 84-87.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/7865567_A_primitive_therizinosauroid_dinosaur_from_the_Early_Cretaceous_of_Utah.

Kirkland, James I.; Madsen, Scott K. (2007). “The Lower Cretaceous Cedar Mountain Formation, eastern Utah: the view up an always interesting learning curve”. Fieldtrip Guidebook, Geological Society of America, Rocky Mountain Section. 2007 Geological Society of America Rocky Mountain Section Annual Meeting, St. George, Utah (May 4-6, 2007). Pages 1-108.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/40662964_The_Lower_Cretaceous_Cedar_Mountain_Formation_eastern_Utah_the_view_up_an_always_interesting_learning_curve_papers_from_a_symposium_of_the_Geological_Society_of_America_at_the_annual_meeting_in_St_Geo.

Senter, Phil; Kirkland, James I.; DeBlieux, Donald D. (2012). “Martharaptor greenriverensis, a New Theropod Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Utah”. PLOS One, volume 7, issue 8 (August 29, 2012): e43911.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0043911.

Zanno, Lindsay E.; Kirkland, James I.; Herzog, Lisa L. (2014). “Second therizinosaurian mass death locality in the Lower Cretaceous Cedar Mountain Formation yields a new taxon”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Abstracts and Programs, 74th Annual Meeting (Berlin, Germany) (November 5-8, 2014), page 260.

https://vertpaleo.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/SVP-2014-Program-and-Abstract-Book-10-14-2014.pdf.

Kirkland, James I.; Suarez, Marina; Suarez, Celina; Hunt-Foster, ReBecca (2016). “The Lower Cretaceous in East-Central Utah—The Cedar Mountain Formation and its Bounding Strata”. Geology of the Intermountain West, volume 3 (October 2016). Pages 101-228.

https://giw.utahgeology.org/giw/index.php/GIW/article/view/11.

Freimuth, William J.; Lively, Joshua R.; Zanno, Lindsay E. (2023). “A therizinosaur in troodontid’s clothing? Reassessing the troodontid Geminiraptor suarezarum in light of new therizinosaurian material from the lower Cretaceous Yellow Cat Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation, Utah, USA”. 14th Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems Conference, Salt Lake City, Utah (June 10, 2023).

https://anatomypubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ar.25219.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment