Introduction

Gastonia was an armored dinosaur measuring approximately 16.5 feet long which lived in western North America during the early Cretaceous Period approximately 135-130 million years ago. The first specimens were found in eastern Utah in 1989, and more have been found since then. Remains belonging to numerous skeletons give us a good idea of how it and other Early Cretaceous ankylosaurians would have looked, although there is still much about it that we don’t know. This article concerns what we do know.

The Prologue: The Discovery of Hoplitosaurus

In 1898, the geologist Nelson Horatio Darton had been prospecting at a place called Calico Canyon, located near the town of Buffalo Gap, Custer County, South Dakota when he spotted some fossil bones. They had been found within rocks belonging to the Lakota Formation, which dates to the early Cretaceous Period approximately 142-122 MYA. Darton initially believed that he had found the partial remains of a stegosaur, and it was described as such by the paleontologist Frederic Lucas shortly afterwards in 1901, who named it Stegosaurus marshi in honor of the famous (or infamous) paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh. However, Lucas quickly began to have second thoughts about this classification. He re-examined the fossils the following year, and he determined that they didn’t belong to Stegosaurus or to any stegosaur at all, but instead belonged to a nodosaurid ankylosaurian similar to the European armored dinosaur Polacanthus. Because of this, in 1902 he re-named the animal Hoplitosaurus, meaning “armored lizard”. Both the name and the classification have stuck ever since. The specimen is currently housed within the Smithsonian Institution (collection ID code: USNM 4752) (Darton 1904, page 389; Lucas 1901, pages 591-192; Lucas 1902, page 435; Carpenter and Kirkland 1998, pages 266-267; Equatorial Minnesota. “Hoplitosaurus”).

However, Early Cretaceous armored dinosaurs such as these were not confined to South Dakota. In the Spring of 1965, Mr. Lynn Ottinger, the owner of the Moab Rock Shop in Moab, Utah, reported to the paleontologist Jim Jensen of Brigham Young University that he had discovered a site which contained fossil bones. The locality lay on the western side of Arches National Park, twenty-one miles north of Moab. Professor Jensen afterwards went out and collected these bones, which were identified as belonging to an armored dinosaur. In October 1967, the locality was re-examined to make a careful study of the site’s geology and to determine the fossils’ geological horizon; additional surveys were conducted in the Spring and Summer of 1968. It was determined that these fossils were found within the Poison Strip Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation, which dated the fossils to 131-119 million years ago during the early Cretaceous Period. In a 1969 article by Norman M. Bodily, the fossils were tentatively identified as belonging to Hoplitosaurus marshi – the same animal that had been found in South Dakota back in 1898. They are believed to constitute 30% of a single skeleton, composed of 7 caudal vertebrae of various sizes, 66 dermal scutes, 14 dermal plates, 3 dermal spines, 3 chevrons, part of 1 rib, 2 pieces of a limb bone, and numerous fragments of armor and limb bones. Many of the bones were in a very poor shape, as they had been damaged by excessive weathering and plant roots. The specimen is currently housed within the collections of Brigham Young University (collection ID code: BYU R245) (Bodily 1969, pages 35-60; Kirkland et al 2016, pages 104-114, 118-147, 154-157; Twitter. Jim Kirkland @Paleojim (May 15, 2020)).

In that same 1969 report written by Norman M. Bodily, he commented that, at the time that he was writing it, a second armored dinosaur specimen had been discovered in Utah five miles southeast of the locality where the Hoplitosaurus skeleton had been found. He remarked that this new find was discovered within approximately the same geological horizon, and that the fossils looked very similar to the Hoplitosaurus skeleton that had been recovered a few years earlier. However, he provided no further information about the appearance of the fossils, he never stated which museum the fossils were housed in, he didn’t provide any collection ID codes for the specimens, and stated that the material had not yet been described (Bodily 1969, page 41). At the time that I am writing this article in March 2024, I have absolutely no idea where these fossils are. This is why it’s VERY important to include as much info as possible within your descriptions.

The Discovery of Gastonia burgei

In 1989, Jim Kirkland, a paleontologist who worked for the educational company Dinamation International, was on a fossil prospecting trip in eastern Utah. One day, he paid a visit to the Moab Rock Shop – the same place where Lynn Ottinger worked during the 1960s – and he saw something which took his breath away. On display in a glass case was a massive 250-pound block of stone which contained the armored back plates of an ankylosaurian dinosaur. Jim Kirkland had a particular love for ankylosaurs, so he became extremely excited when he saw this. The rock shop owner showed Kirkland where he had found the fossils – a hillside located north of Arches National Park – and Kirkland decided that he needed to launch an expedition there as soon as possible (“Utah Rocks Yield 2 New Species of Dinosaurs”).

The following year in the Summer of 1990, a joint venture carried out by the College of Eastern Utah (CEU) and Dinamation International was prospecting for fossils in the area where the remains of the armored dinosaur had been discovered earlier. The goal of the expedition was to see if they could find any more remains of this tantalizing creature. One of the team members named Robert Gaston arrived at the dig site where the ankylosaur osteoderms had been discovered, and he found even more bones. The dig-site was named “Gaston Quarry” in his honor. The rock layers of the quarry were dated to the upper part of the Yellow Cat Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation, approximately 135-132 million years ago, and consisted of inter-bedded limestone and siltstone, which was explained as being probably caused by sequences of floods on the edge of a lake. The dig team excavated there in 1990, 1991, and 1992. In total, hundreds of fossil specimens were discovered. Among these were a few iguanodont teeth, bones belonging to a large raptor dinosaur, and a large number of bones belonging to multiple individuals of an armored ankylosaurian dinosaur. The exact number of individuals which were found at Gaston Quarry varies depending on which source you look at, ranging from 4, 5, or 6 individuals; of these, 6 is the number that’s seen in most sources (“Utah Rocks Yield 2 New Species of Dinosaurs”; “A Creature to Make T. Rex Tremble”; Kirkland 1998, page 271-273, 276; Kirkland et al 2016, pages 114, 117, 130; “March 10th, 2021 NMSR Meeting – ‘Feathering Utahraptor: History of Dromaeosaur Discoveries’”; “Tate Geological Museum’s Spring Lecture Series 2021: Cretaceous Dinosaurs- part 3 – The Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah: North America’s Most Complete Early Cretaceous Record”).

Five braincases were found at Gaston Quarry. The holotype skull (CEUM 1307) was the largest with the bones fused together, and it was determined to belong to an adult. This skull was larger than the other skull material on the site, indicating that the remaining individuals were sub-adults (Kirkland 1998, page 276).

In 1993, the large raptor dinosaur was officially named Utahraptor, and it quickly grabbed the public’s attention (Kirkland et al 1993, pages 1-16). However, the armored dinosaur which had been found alongside it at “Gaston Quarry” was still un-named. Jim Kirkland unofficially ascribed it the name “Gastonia”, named in reference to Robert Gaston. The name “Gastonia” was mentioned in various works of literature and popular media during the mid 90s, but a formal description had not been given in any scientific publication, so the name was used only unofficially (Bakker 1994, page 89; Bakker 1996; Paleoworld, season 3, episode 6 – “Armored Dinos”; Kirkland 1997, page 98).

The name Gastonia burgei first appeared in a professional scientific paper in 1998, specifically in an overview of North American ankylosaurs written by Kenneth Carpenter and Jim Kirkland. However, while the name was given and the holotype specimen was mentioned, no further information was stated (Carpenter and Kirkland 1998, pages 249-250, 268). An official description of the animal appeared in a follow-up article written by Jim Kirkland which appeared within the same journal issue. The genus name was in honor of Robert Gaston who discovered the skeleton. The species name was in honor of Donald L. Burge, the director of the Prehistoric Museum of the College of Eastern Utah. The holotype specimen is housed within the Prehistoric Museum (collection ID code: CEU 1307) (Kirkland 1998, pages 271-273).

While Gastonia burgei was being given its official description, more specimens were being uncovered elsewhere in Utah. Earlier in 1975 and 1978, Jim Jensen and his colleagues had excavated a site in eastern Utah named Dalton Wells, located approximately 12.5 miles (20 km) northwest of the town of Moab. In total, about 800 specimens were gathered during those two excavations, but only a small number of them have been prepared and studied. They are currently housed in the collections of Brigham Young University. In 1994, a team of paleontologists and geologists from Brigham Young University and the Museum of Western Colorado went back to Dalton Wells to prospect for bones. The initial intention was to look for sauropod and iguanodont fossils, but they quickly got more than what they had bargained for. In total, the site covered about 4,000 square meters in area, far too large to excavate within a single dig season. Only 180 square meters were excavated, but even so, the payoff was stupendous. The earlier digs which had been conducted at Dalton Wells during the 1970s produced about 800 fossil specimens, but in 1994 the excavators hit a fossil bonanza. Within the 180-meter area that they dug, over 5,000 bones (either whole or in fragments) were unearthed belonging to at least nine different species of dinosaurs and four species of other animals, making it one of the richest concentrations of fossil bones anywhere in the American West. For several years, dig teams returned to Dalton Wells to carry on the daunting work of collecting and cataloguing bone fragments, many of which measured no larger than the size of a marble. Most of the fossils belonged to sauropods, but other fossils which were unearthed belonged to iguanodonts, the nodosaur Gastonia, the primitive ornithomimosaur Nedcolbertia, and to Utahraptor. A report published in 2009 stated that 590 osteoderms and 316 skeletal elements which had been ascribed to Gastonia had been uncovered at Dalton Wells. The report’s authors claimed that these specimens belonged to at least nine individuals, being one adult and eight sub-adults. Considering the immense number of fossils which have been unearthed at Dalton Wells, which are still undergoing preparation and analysis after almost thirty years, there are likely many more still encased within the matrix that haven’t been seen yet. Furthermore, given that the Dalton Wells Quarry occupies such a vast swath of territory, and only a small section of it has been excavated so far (only 4.5% of the site’s total area), it is very possible that even more fossils are still lying there buried within the rock waiting to be discovered (Kirkland et al 1997, page 92; Eberth et al 2006, pages 217-218; Britt et al 2009, pages 1-2, 6, 8, 11, 18-19; “March 10th, 2021 NMSR Meeting – ‘Feathering Utahraptor: History of Dromaeosaur Discoveries’”).

Gastonia burgei seems to have been one of the most common dinosaurs found within the upper Yellow Cat Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation. As of 2009, 15 individuals have been found (6 from Gaston Quarry and another 9 from Dalton Wells). Only the turiasaurian sauropod dinosaur Moabosaurus (at least 18 confirmed specimens from Dalton Wells, and possibly an additional 17, but these might belong to different sauropod species) and the dromaeosaurid theropod Utahraptor (at least a dozen, and almost certainly more) compete with these numbers (Britt et al 2009, pages 1, 6, 8, 11, 19; Britt et al 2017, pages 189-243).

A New Species

In 1999, paleontologist Lorrie McWhinney of the Western Interior Paleontological Society discovered a fossil-rich site located east of Arches National Park. The bonebed measured 30 cm thick and covered 8,600 square meters in area. The locality was subsequently named “Lorrie’s Site” (Kinneer et al 2026, pages 41, 45; “Amateur Spotlight: Lorrie McWhinney & Angela Matthias”).

There has been some dispute as to which member of the Cedar Mountain Formation this bonebed was located within. McDonald et al (2010) showed in a stratigraphic map that Lorrie’s Site” is located within the uppermost part of the Poison Strip Member close to the contact line between it and the upper Ruby Ranch Member. This would date the rock layer to approximately 119 MYA (McDonald et al 2010: e14075). However, Kinneer et al (2016) states that it was located within the lower part of the Ruby Ranch Member (Kinneer et al 2016, page 41). Still, most sources which have been published afterwards claim that the site is from the upper Poison Strip (Kirkland et al 2016, page 117; Twitter. Jim Kirkland @Paleojim (May 15, 2020)).

The majority of the fossils which were found at Lorrie’s Site belonged to an armored dinosaur which strongly resembled Gastonia burgei, but there were some slight differences. In 2016, the new species was officially named Gastonia lorriemcwhinnyae in honor of Lorrie McWhinney who discovered the site where the fossils were found (Kinneer et al 2016, pages 41-42, 45-46, 76). In the words of the article which named it, “It differs from Gastonia burgei in having a flat skull roof, short paroccipital processes that is proportionally less expanded distally, short postacetabular process of ilium that is only 36% of the length of the preacetabular process as compared to 56% in G. burgei, and an ischium that is smoothly curved ventromedially without kink at its midpoint” (Kinneer et al 2016, page 37). The holotype specimen is “DMNH 49877”, and is currently housed within the Denver Museum of Nature and Science (Kinneer et al 2016, page 45). In an online lecture from 2021, Jim Kirkland stated that at least 12 individuals are known for Gastonia lorriemcwhinnyae (“Tate Geological Museum’s Spring Lecture Series 2021: Cretaceous Dinosaurs- part 3 – The Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah: North America’s Most Complete Early Cretaceous Record”).

Jim Kirkland has hypothesized that Gastonia lorriemcwhinnyae is actually Hoplitosaurus, another armored dinosaur known only from partial remains which was discovered in South Dakota in 1898 (“Tate Geological Museum’s Spring Lecture Series 2021: Cretaceous Dinosaurs- part 3 – The Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah: North America’s Most Complete Early Cretaceous Record”). As mentioned earlier, an armored dinosaur which had been tentatively identified as Hoplitosaurus in 1969 had been found within the rocks of the Poison Strip Member on the western side of Arches National Park. The bones of Gastonia lorriemcwhinnyae had been found within the same stratigraphic layer on the eastern side of Arches National Park. There is also a morphological similarity between the two. Both Hoplitosaurus marshi and Gastonia lorriemcwhinnyae, as well as their close European relative Polacanthus foxii are distinctive for possessing peculiar osteoderms referred to as “splates” (a portmanteau of “spiny plates”). By contrast, Gastonia burgei didn’t possess splates, but possessed short rounded osteoderms or large triangular blade-like spines (Bodily 1969, pages 47-57; Twitter. Jim Kirkland @Paleojim (May 15, 2020)).

Possibly More Species of Gastonia?

The remains of Gastonia burgei have been found within the upper part of the Yellow Cat Member, and Gastonia lorriemcwhinnyae was found within the overlying Poison Strip Member. However, there’s the possibility that there are more species of this animal.

One possible example was found within the Buckhorn Conglomerate Member, which rests below the Yellow Cat Member and dates to the earliest part of the Cretaceous Period 144-140 MYA. The Buckhorn Conglomerate is recognizable for a layer of chert pebbles and cobbles measuring up to 25 meters thick in some locations. These pebbles and cobbles originated from late Paleozoic-dated strata which were upthrust into prehistoric mountains within Nevada and northwestern Arizona, and afterwards weathered out and became part of a river system flowing in a northeastern direction (Kirkland et al 2016, page 110). The remains of an ankylosaurian were found within the Buckhorn Conglomerate, which is remarkable not only for its own sake, but also due to the fact that animal remains are very scarce within this layer. The fossils consist of dorsal and caudal vertebrae, a few ribs, parts of the pelvis, and several osteoderms (Kirkland et al 2016, pages 110-111; “Tate Geological Museum’s Spring Lecture Series 2021: Cretaceous Dinosaurs- part 3 – The Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah: North America’s Most Complete Early Cretaceous Record”).

In 2015 at Peter Lougheed Provincial Park, located in southwestern Alberta, Canada within rock strata which was dated to the Pocaterra Creek Member of the Cadomin Formation, there were found fossils of three partial ankylosaurian osteoderms (collection ID codes: UALVP 59792.1-3), and a piece of a turtle’s plastron (collection ID code: UALVP 59793). The stratum where these fossils were found was dated to the late Berriasian Stage (approximately 142-140 MYA), based upon previously-conducted palynomorph analyses of the Pocaterra Creek Member as well as of the underlying and overlying rock layers (Nagesan et al 2020, pages 542-552; “An Ankylosaur from the Foothills of Alberta”). This would make this rock layer concurrent with the Buckhorn Conglomerate Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation of eastern Utah. The osteoderms have been hypothesized as belonging to a polacanthine nodosaurid ankylosaurian due to their similarity to other polacanthine osteoderms found elsewhere. If this hypothesis is correct, then it’s also possible that this might be the same species which was uncovered within the Buckhorn Conglomerate (Kirkland et al 2016, pages 110-114). The fossils which were recovered from Peter Lougheed Provincial Park are currently housed in the collections of the University of Alberta Laboratory for Vertebrate Palaeontology (UALVP), located in Edmonton, Alberta.

Within the lower part of the Yellow Cat Member, remains which have been attributed to one or possibly two new species of ankylosaurians were found at a site called Doelling’s Bowl. One of these was a very large animal, estimated to have been twice the size of Gastonia, which would make it 30-35 feet long (Kirkland et al 2016, pages 125, 127)! Jim Kirkland and his colleagues stated “The polacathine ankylosaurs at Doelling’s Bowl represent a new taxon based on comparisons with the braincases of the Jurassic Gargoyleosaurus and Mymoorapelta and the 10 known braincases of Gastonia” (Kirkland et al 2016, page 122). This specimen is currently under study at the Prehistoric Museum in Price, Utah (“Tate Geological Museum’s Spring Lecture Series 2021: Cretaceous Dinosaurs- part 3 – The Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah: North America’s Most Complete Early Cretaceous Record”). This as-yet-unnamed animal has been given the informal designation “Polacanthine A” to distinguish it from other unnamed polacanthine species (Kirkland et al 2023). In a Twitter post dated to March 21, 2022, Jim Kirkland referred to this animal as “Gamera”, named in reference to the monstrous turtle kaiju from the Godzilla movies (Twitter. Jim Kirkland @Paleojim (March 21, 2022)).

In 2021, Jim Kirkland announced in an online lecture that he was at that moment in the process of writing papers officially naming three new species of armored dinosaurs. In October 2023, he made a presentation at the annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in which he asserted that there are three as-yet-unnamed polacanthine ankylosaurs found within the earliest Cretaceous strata of Utah’s Paradox Basin circa 144-135 MYA. According to this presentation, at Doelling’s Bowl, which is situated within the lowest quarter of the Yellow Cat Member, the remains of three individuals consisting of one adult and two juveniles of “Polacanthine B” were found, along with many isolated skeletal elements.

Description

The type species Gastonia burgei was classified as being a polacanthine nodosaurid ankylosaurian dinosaur, closely related to Polacanthus, Hylaeosaurus, and Hoplitosaurus. Although numerous partial skeletons have been uncovered, no complete skeleton of Gastonia has been found so far. This makes it difficult to determine what its size would have been when fully grown. Numerous sources state that it measured 16-20 feet (5-6 meters) long, with a median length of 18 feet. This would make it slightly larger than its close European relative Polacanthus (18 feet versus 15 feet, respectively) (Kirkland 1998, pages 271-273).

Despite numerous similarities noted between it and Polacanthus, there are enough differences between the two to warrant Gastonia’s classification as a separate genus. Gastonia possessed only 3 sacral vertebrae, as opposed to 4 seen in Polacanthus, it has a differently-shaped pelvis, a differently-shaped femur, and a shorter and more robust tibia. The large triangular spines were larger than that seen in Polacanthus, and the tail spines were less recurved (Kirkland 1998, pages 271-273, 276).

The top of the skull is somewhat domed, and this has led some to speculate that this had a part to play in intraspecies behavior, as will be described later on. The front of the upper jaw had a prominent notch in the middle. There is a small triangular projection extending downwards directly underneath the eye socket, and another on each side of the back of the skull at the top of the cranium, extending diagonally backwards-and-outwards. The skull also features large sideways-facing nares (Kirkland 1998, page 272).

As with all thyreophoran dinosaurs, the most distinctive aspect of its anatomy is its armor, and the body army of Gastonia burgei was very impressive, featuring large shark fin-shaped blades. However, it’s difficult to ascertain the precise arrangement and orientation of the osteoderms because the specimens were disarticulated. Reconstructions of this animal show a variety of arrangements, but all pertaining more-or-less to the same overall form. At the moment, it’s impossible to say which one of these reconstructions is the most accurate. Neck armor consists of three pairs of quarter-rings, each terminating in a sideways-projecting triangular spike. These neck spines become longer the closer they are to the shoulders. The sideways-facing spines on the neck are triangular in cross-section with a sharp front edge and a deep groove running along the back edge. The lateral-pointing spikes on the side of the animal’s body are hollow-based, whereas the dorsal osteoderms are solid-based. The armor on the animal’s back consists of circular or oval ridged osteoderms measuring 3.5-5.5 cm in diameter intermixed with smaller pebble-like osteoderms typically measuring 0.6-2.5 cm in diameter; the armor on the back is NOT co-ossified into a single solid unit. There is a row of rhomboid-shaped osteoderms running along the front of the pelvic shield. Each of these osteoderms has a low ridge running along the lateral-facing edge, and is bordered by boney ossicles measuring 1-2 cm in diameter. The armored pelvic shield consisted of large oval-shaped ridged osteoderms embedded amidst smaller pebble-shaped osteoderms; this pelvic shield IS fused together into a single solid piece of armor. Such armor was also seen in creatures like Gargoyleosaurus, Hylaeosaurus, and Polacanthus. A line of triangular plates arranged along each side of the tail. The tail’s vertebrae indicate that the tail was good at flexing from side-to-side, but not so well up-and-down, although the plates themselves would have restricted the tail’s lateral flexion. These osteoderms are not as recurved as seen in Polacanthus (Kirkland 1998, pages 271-277; Arbour et al 2011, pages 298, 300-301; Kinneer et al 2016, pages 71-76).

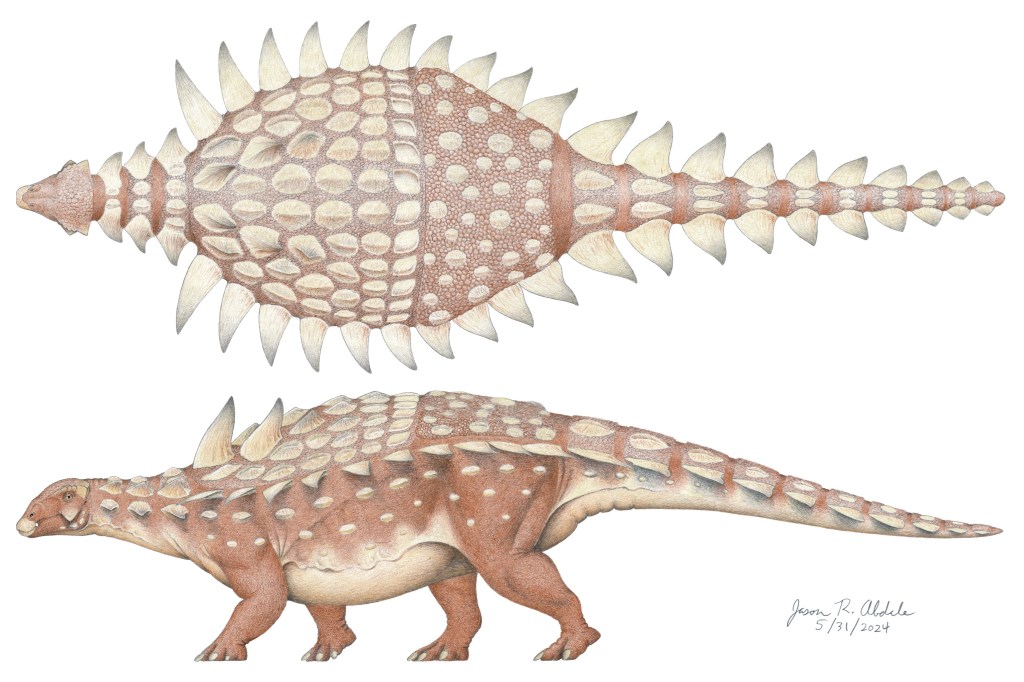

The process of researching this article and of preparing the paleo-art for this article led to some interesting finings concerning Gastonia burgei’s anatomy. For starters, the animal’s total size was determined with greater accuracy. To ensure that my illustration was as accurate as possible, I obtained photographs and exact measurements of numerous specimens of Gastonia burgei’s fossils, including the skull, limb bones, hip bones, and osteoderms from various places on its body. I resized all of these photographs so that they were exactly in-scale to each other so that they were one-tenth life-size so that the whole image would fit on my computer screen. I regularly posted my progress on the Cedar Mountain Formation page on Facebook, and I frequently received input from various paleontologists, notably Dr. Jim Kirkland. Then I measured the final reconstruction, and multiplied it by ten to determine the creature’s life-size. The final measurement which was obtained was 16.45 feet long.

Another thing which was surprising was that the creature’s overall appearance was dramatically changed from earlier reconstructions. Changing the total number of cervical osteoderms from two rows to three increased the length of Gastonia’s neck by 50%. The tail turned out to be shorter, thinner, and had fewer osteoderms arranged along its sides than earlier paleo-art had previously showed. The size and arrangement of the armor plates were also changed. For the past three decades, reconstructions had portrayed Gastonia with huge Desmatosuchus-like scythe-shaped horizontal spines coming off of its shoulders, gradually progressing to smaller and smaller horizontal spines towards the hips, and also with two rows of humungous sharkfin-like spines coming up out of its back. However, the largest lateral shoulder spines which I’ve seen pictures and measurements of is the right lateral spine CEUM 3857, which measures about 14.2 inches long, and the largest dorsal spine that I’ve seen pictures and measurements of is BYU VP13654 which measures about 15 inches along its anterior edge, at least according to the 10 cm scale bar which accompanied the photos of those two elements. Both of these measurements are far smaller than the spines shown in previously-made illustrations of Gastonia burgei. The use of these two elements, which as I mentioned before are far smaller than the spines shown in earlier paleo-art, dramatically changed Gastonia’s look. It wasn’t quite as visually unique as it previously was, and ended up bearing a pretty close resemblance to other nodosaurids such as Hylaeosaurus, Polacanthus, Silvisaurus, and Struthiosaurus.

Gastonia burgei. © Jason R. Abdale (May 31, 2024).

Paleo-Biology

As mentioned earlier, Gastonia burgei seems to have been one of the most common species within its environment, with a total of 15 individuals found so far. There are likely many more, since the multitudinous fossil specimens which were unearthed at Dalton Wells have been undergoing meticulous study for the past thirty or so years, and there are still many specimens which have not been analyzed yet. Furthermore, considering the immense expansiveness of the fossil beds at Dalton Wells, and considering that only a small percentage of this area has been examined by paleontologists, there are assuredly thousands or even hundreds of thousands of fossils still buried there awaiting discovery.

Of the 9 specimens which were found at Dalton Wells, one was an adult and the remaining eight were sub-adults. This led Bill Kinneer and his colleagues to propose that Gastonia was a herding animal (Kinneer et al 2016, page 40).

Jim Kirkland hypothesized that Gastonia might have fought against each other in pushing contests. He observed that the curved thickened skull was similar in shape to that seen in dinocephalian synapsids which are believed to have engaged in head-pushing matches with each other. He also observed that Gastonia had a slightly flexible braincase, which may have absorbed the shock of impact upon the skull. He therefore believes that Gastonia might have engaged in intra-species combat, particularly head-butting or head-pushing contests with each other, likely accompanied with a lot of snorting, bellowing, and bluster to intimidate rivals (Kirkland 1998, pages 277-278).

Post-Script

If you enjoy these drawings and articles, please click the “like” button, and leave a comment to let me know what you think. Subscribe to this blog if you wish to be immediately informed whenever a new post is published. Kindly check out my pages on Redbubble and Fine Art America if you want to purchase merch of my artwork. Also, please consider becoming a patron on my Patreon page so that I can afford to purchase the art supplies and research materials that I need to keep posting art and articles onto this website. And, as always, keep your pencils sharp.

Bibliography

Books and Articles

Arbour, Victoria, M.; Burns, Michael E.; Currie, Philip J. (2011). “A Review of Pelvic Shield Morphology in Ankylosaurs (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)”. Journal of Paleontology, volume 85, issue 2 (2011). Pages 298-302.

https://www.academia.edu/82812131/A_review_of_pelvic_shield_morphology_in_ankylosaurs_Dinosauria_Ornithischia_.

Bakker, Robert. Raptor Red. New York: Bantam Books, 1996.

Bakker, Robert T. (1994). “Unearthing the Jurassic”. Science Year 1995: The World Book Annual Science Supplement – A Review of Science and Technology during the 1994 School Year. Chicago: World Book Inc., 1994. Pages 77-89.

https://archive.org/details/scienceyear1995w00chic.

Bodily, Norman M. (1969). “An Armored Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Utah”. Brigham Young University Geological Studies, volume 16, issue 3 (December 1969). Pages 35-60.

https://geology.byu.edu/0000017c-dde1-d27f-abfe-fde1f5f10001/an-amoured-dinosaur-from-the-lower-cretaceous-of-utah-norman-m-bodily-pdf.

Britt, Brooks B.; Eberth, David A.; Scheetz, Rod D.; Greenhalgh, Brent W.; Stadtman, Kenneth L. (2009). “Taphonomy of debris-flow hosted dinosaur bonebeds at Dalton Wells, Utah (Lower Cretaceous, Cedar Mountain Formation, USA)”. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, volume 280 (June 2009). Pages 1-22.

Britt, Brooks B.; Scheetz, Rodney D.; Whiting, Michael F.; Wilhite, D. Ray (2017). “Moabosaurus utahensis, n. gen., n. sp., a new sauropod from the early Cretaceous (Aptian) of North America”. Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan, volume 32, issue 11 (April 10, 2017). Pages 189-243.

https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/136227.

Carpenter, Kenneth; Kirkland, James I. (1998). “Review of Lower and Middle Cretaceous Ankylosaurs from North America”. In Lucas, S.G.; Kirkland, James I.; Estep, J.W., eds. Lower and Middle Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 14. Pages 249-270.

https://books.google.com/books?id=yF4fCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA249#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Darton, Nelson Horatio (1904). “Comparison of the Stratigraphy of the Black Hills, Bighorn Mountains, and Rocky Mountain Front Range”. Geological Society of America Bulletin, volume 15 (1904). Pages 379-448.

https://archive.org/details/sim_geological-society-of-america-bulletin_1904_15.

Doelling, Hellmut H.; Kuehne, Paul A. (2013). “Geologic map of the Mollie Hogans 7.5’ quadrangle, Grand County, Utah”. Utah Geological Survey. https://www.geo.arizona.edu/~reiners/fortransfer/Pages%20from%20Mollie%20Hogans%20m-259.pdf.

Eberth, David A; Britt, Brooks B.; Scheetz, Rod; Stadtman, Kenneth L; Brinkman, Donald B. (2006). “Dalton Wells: Geology and significance of debris-flow-hosted dinosaur bonebeds in the Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of eastern Utah, USA”. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, volume 236. Pages 217-245.

https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/49882404/j.palaeo.2005.11.02020161026-6104-1m6tq92-libre.pdf?1477489419=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DDalton_Wells_Geology_and_significance_of.pdf&Expires=1652625588&Signature=DbIsCQTwiPGd5pNw6kQeggbiB8JbkhFQtMI8DPKD4TcN6t-thxwSM2x1HO8Dx9K20waRgLt7qdluUhGwWXSwj8TBtrs0w4P0t56u6GUZxWRaQMxNxA2SZJTyBwxsn5GPOjhsDffOHPJhxIF4WS9K1vSJQGbbU3dEC51KVIswVm9GSPm1e69DHWCS4oU0px4Z~05gmHnG8Yv-IMEgkyF5EEyUJCmSqsVOGP9HFMQE9sIrEgEdhEPVCInSrlfsQsL-lxPWewZTAq4BdN6UEovm1qVAy6nxXva3kdToDWtVs0BQN0y8iv8Furk7bYcdNklaTMt-Jc52xiVzOQO0Wl83AA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA.

Kinneer, Billy; Carpenter, Kenneth; Shaw, Allen (2016). “Redescription of Gastonia burgei (Dinosauria: Ankylosauria, Polacanthidae), and description of a new species”. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie – Abhandlungen, volume 282, issue 1 (October 2016). Pages 37-80.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308878540_Redescription_of_Gastonia_burgei_Dinosauria_Ankylosauria_Polacanthidae_and_description_of_a_new_species.

Kirkland, James I. (1997). “Cedar Mountain Formation”. In Currie, Philip J.; Padian, Kevin, eds. Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press, 1997. Page 98.

Kirkland, James I. (1998). “A polacanthine ankylosaur (Ornithischia: Dinosauria) from the Early Cretaceous (Barremian) of eastern Utah”. In Lucas, S.G.; Kirkland, James I.; Estep, J.W., eds. Lower and Middle Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 14. Pages 271-281.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Lower_and_Middle_Cretaceous_Terrestrial/yF4fCgAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

Kirkland, James I.; Britt, Brooks; Burge, Donald L.; Carpenter, Kenneth; Cifelli, Richard; DeCourten, Frank; Eaton, Jeffery; Hasiotis, Stephen; Lawton, Tim (1997). “Lower to Middle Cretaceous Dinosaur Faunas of the Central Colorado Plateau: A Key to Understanding 35 Million Years of Tectonics, Evolution, and Biogeography”. Brigham Young University Geology Studies, volume 42, issue 2. Pages 69-103.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259021967_Lower_to_middle_Cretaceous_dinosaur_faunas_of_the_central_Colorado_Plateau_a_key_to_understanding_35_million_years_of_tectonics_sedimentology_evolution_and_biogeography.

Kirkland, James Ian; Burge, Donald; Gaston, Robert (1993). “A large dromaeosaur (Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of eastern Utah”. Hunteria, volume 2, issue 10 (June 18, 1993). Pages 1-16.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285714464_A_large_dromaeosaur_Theropoda_from_the_Lower_Cret.

Kirkland, James I.; DeBlieux, Donald D.; Madsen, Scott K.; Hunt, Gary J. (2012). “New dinosaurs from the base of the Cretaceous in eastern Utah suggest that the “so-called” basal Cretaceous calcrete in the Yellow Cat Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation, while not marking the Jurassic-Cretaceous unconformity represents evolutionary time”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Abstracts and Program (October 2012). Pages 121-122.

https://vertpaleo.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/SVP-Abstract-Book_12_web.pdf.

Kirkland, James I.; DeBlieux, Donald D.; Warner-Cowgill, Ethan; Lively, Joshua (2023). “New Polacanthine Ankylosaurs from the Basal Cretaceous (Berriasian), lower Yellow Cat Member (YCM) of the Cedar Mountain Fm. (CMF), Northern Paradox Basin, Grand County, Utah”. Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (October 2023).

Kirkland, James I.; Suarez, Marina; Suarez, Celina; Hunt-Foster, ReBecca (2016). “The Lower Cretaceous in East-Central Utah—The Cedar Mountain Formation and its Bounding Strata”. Geology of the Intermountain West, volume 3 (October 2016). Pages 101-228.

https://giw.utahgeology.org/giw/index.php/GIW/article/view/11.

Lucas, Frederic A. (1901). “A New Dinosaur, Stegosaurus marshi, from the Lower Cretaceous of South Dakota”. Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum, volume 23, issue 1224 (1901). Pages 591-592.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/7511709#page/657/mode/1up.

Lucas, Frederic A. (1902). “Paleontological Notes – A new generic name for Stegosaurus marshi”. Science, volume 16, issue 402 (September 12, 1902). Page 435.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/31257497#page/449/mode/1up.

Los Angeles Times. “Utah Rocks Yield 2 New Species of Dinosaurs: Paleontology: Bones of a vicious killer and a ‘war machine’ may help scientists fill a gap in the evolutionary picture”, by Mike Dennison (October 25, 1992).

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-10-25-me-832-story.html.

McDonald, Andrew T.; Kirkland, James I.; DeBlieux, Donald D.; Madsen, Scott K.; Cavin, Jennifer; Milner, Andrew R. C.; Panzarin, Lukas (2010). “New basal iguanodonts from the Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah and the evolution of thumb-spiked dinosaurs”. PloS One, volume 5, issue 11 (November 22, 2010): e14075.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0014075.

Nagesan, Ramon S.; Campbell, James A.; Pardo, Jason D.; Lennie, Kendra I.; Vavrek, Matthew J.; Anderson, Jason S. (2020). “An Early Cretaceous (Berriasian) fossil-bearing locality from the Rocky Mountains of Alberta, yielding the oldest dinosaur skeletal remains from western Canada”. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, volume 57, issue 4 (April 2020). Pages 542-552.

https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA620471951&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=00084077&p=AONE&sw=w&userGroupName=nysl_oweb&isGeoAuthType=true

Poulton, T. P.; Christopher, J. E.; Hayes, B. J. R.; Losert, J.; Tittenmore, J.; Gilchrist, R. D. (1994). “Chapter 18 – Jurassic and Lowermost Cretaceous Strata of Western Canada Sedimentary Basin”. In Mossop, Grant; Shetsen, Irina, eds., Geological Atlas of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin. Calgary: Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists, 1994. Pages 297-316.

https://www.cspg.org/common/Uploaded%20files/pdfs/documents/publications/atlas/geological/atlas_18_jurassic_and_lowermost_cretaceous.pdf.

The New York Times – Science Times. “A Creature to Make T. Rex Tremble”, by Malcolm W. Browne (July 21, 1992). https://www.nytimes.com/1992/07/21/science/a-creature-to-make-t-rex-tremble.html. Accessed on June 23, 2022.

Websites

Equatorial Minnesota. “Hoplitosaurus”. https://equatorialminnesota.blogspot.com/2017/06/hoplitosaurus.html. Accessed on July 5, 2022.

MyFossil. “Amateur Spotlight: Lorrie McWhinney & Angela Matthias”. https://www.myfossil.org/amateur-spotlight-lorrie-mcwhinney-angie-matthias/. Accessed on March 25, 2023.

Twitter. Jim Kirkland @Paleojim (May 15, 2020). https://twitter.com/paleojim/status/1261441040424173570.

Twitter. Jim Kirkland @Paleojim (March 21, 2022).

https://twitter.com/Paleojim/status/1506064482451173376/photo/1.

Videos

Paleoworld, season 3, episode 6 – “Armored Dinos”. The Learning Chanel, 1996. https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x7zq4nh.

YouTube. Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology. “An Ankylosaur from the Foothills of Alberta” (March 27, 2020).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gmTTtHP8VuY.

YouTube. TheNMSR. “March 10th, 2021 NMSR Meeting – ‘Feathering Utahraptor: History of Dromaeosaur Discoveries” (March 15, 2021). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mY5lWGC-ogA. Accessed on March 14, 2022.

YouTube. Tate Geological Museum. “Tate Geological Museum’s Spring Lecture Series 2021: Cretaceous Dinosaurs- part 3 – The Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah: North America’s Most Complete Early Cretaceous Record” (May 11, 2021). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Thhb6Jy-Acw. Accessed on March 14, 2022.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment