Megaraptor was a 25 foot long carnivorous dinosaur which lived in Argentina during the late Cretaceous Period 90 million years ago. The fossils of this animal were discovered by the Argentinian paleontologist Fernando Novas in northwestern Patagonia, Argentina in 1996. They were found within the Portezuelo Formation (formerly named the Rio Neuquen Formation), which dates to the Turonian and Coniacian Stages of the late Cretaceous Period, 93-86 million years ago. Only a few bones were found, but the most awesome of them was a massive claw measuring 15 inches long! Novas thought that this claw looked similar to the claws of dromaeosaurid raptor dinosaurs. Up to that point, no raptors had been found within the Southern Hemisphere. Moreover, this claw was far bigger than the claws of any other raptor, even bigger than Utahraptor. Based upon the size of the claw, and comparing it with the size of the foot claws of the well-known raptor dinosaur Deinonychus, it was believed that this animal measured 25 feet (8 meters) long. In 1998, the animal was officially named Megaraptor namunhuaiquii. The species name comes from the native Mapuche language and means “foot lance” in reference to the giant claw which was believed to be a raptorial killing claw (Novas 1998, pages 4-9). The holotype specimen is currently housed within the Museo Carmen Funes in the town of Plaza Huincul, Argentina (collection ID code: MCF-PVPH 79).

I first became aware of Megaraptor’s existence in August 1999 when I was 13 years old and I saw a TV series on The Learning Channel (which nowadays is anything but) called “When Dinosaurs Ruled”, narrated by Jeff Goldblum. For a while, Megaraptor was one of my favorite dinosaurs and I drew it repeatedly.

It must be said that, while Megaraptor was believed to have been an unusually large South American raptor dinosaur, even Fernando Novas was skeptical of this. He noted that while the large claw was similar in shape to those belonging to raptors, none of the other bones looked similar to either dromaeosaurid or troodontid raptors. The ulna resembled the ulnae belonging to allosaurs and megalosaurs, while the third metatarsal more closely resembled that belonging to coelurosaurs. Therefore, while Fernando Novas stated that it was likely a raptor theropod, he never officially classified it as such. Instead, he tentatively classified it as a member of the clade Coelurosauria – a large theropod group which includes basal coelurosaurs like Coelurus and Ornitholestes, the compsognathids, the tyrannosaurs, the ornithomimids, the oviraptorosaurians, the therizinosaurs, and the raptors (Novas 1998, pages 6-8).

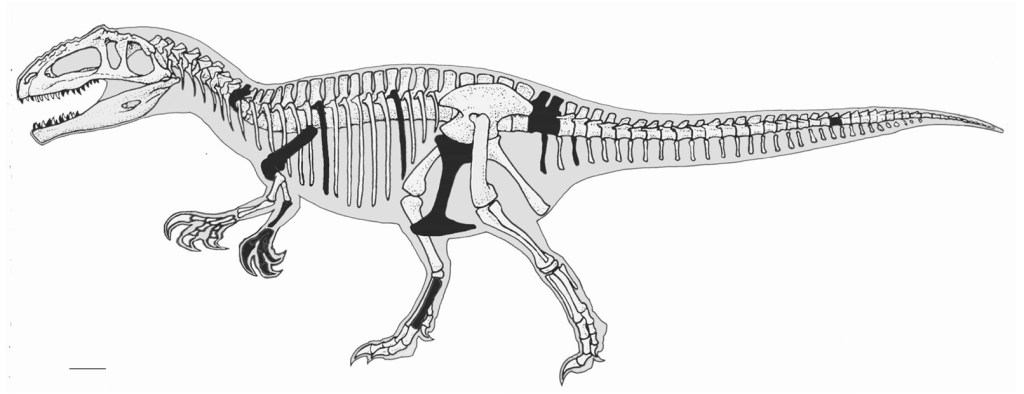

In June 2002, more fossils of Megaraptor were discovered along with fossils belonging to the theropod Unenlagia, titanosaurid sauropods, iguanodontian ornithopods, fish, turtles, crocodiles, and pterosaurs, as well as eggshell fragments and numerous plant fossils. These new Megaraptor specimens consisted of an articulated left scapulocoracoid, a right pubis, a cervical vertebra, two anterior caudal vertebrae fused with one haemal arch, two isolated haemal arches, and a right fourth metatarsal; these fossils were housed within the Museo de la Universidad Nacional del Comahue, Paleontología de Vertebrados and were given the collection ID code MUCPv 341. A formal description of these new fossils was published in 2004. In this report, it was shown that the large claw which had been found by Fernando Novas in 1996 didn’t belong on the foot, but instead belonged on the hand. It was also noted that Megaraptor’s anatomy bore more resemblances to carcharodontosaurs and spinosaurs than to dromaeosaurid raptors (Calvo et al 2004, pages 565-575). So Megaraptor’s anatomy appeared to have possessed a bizarre hodge-podge of characteristics from several theropod groups including carcharodontosaurs, megalosaurs, and spinosaurs.

Hypothetical skeletal reconstruction of Megaraptor namunhuaiquii as a carcharodontosaurid. The fossils which were found are shown in black. Scale bar = 30 cm. Calvo, Jorge O.; Porfiri, Juan D.; Veralli, Claudio; Novas, Fernando E.; Poblete, Federico (2004). “Phylogenetic status of Megaraptor namunhuaiquii Novas based on a new specimen from Neuquén, Patagonia, Argentina”. Ameghiniana, volume 41, issue 4 (December 30, 2004). Page 567.

In 2007, in a paper describing the fossils of the Antarctic theropod Cryolophosaurus and its relationship to other theropod genera, it was stated that Megaraptor was a carcharodontosaur. According to this report, “This relationship is primarily supported by several characters of the cervical vertebrae, including the number and orientation of cervical pleurocoels, and the presence of a marked prezygapophyseal-epipophyseal lamina. Megaraptor also shares with several carcharodontosaurids the presence of hyposphene/hypantrum-like accessory articulations in the cervical vertebrae, and the presence of pleurocoels in the caudal vertebrae…Megaraptor is recovered as a derived carcharodontosaurid in the present analysis, being more closely related to Giganotosaurus and Carcharodontosaurid (sic) than to the basal-most carcharodontosaurid, Tyrannotitan. Despite this result, Megaraptor still possesses several features that suggest spinosauroid affinities” (Smith et al 2007, pages 411, 414).

As stated earlier, it was shown in 2004 that the claw belonged to the hand not the foot, like Baryonyx. Could Megaraptor have been a spinosaur? Spinosaurid theropods had been found in South America before, but they had been known from Brazil, including Irritator. In 2008, it was proposed that Megaraptor might be a spinosaur due to several similarities to spinosauroid anatomy (Smith et al 2008, pages 2,085-2,093).

In 2010, the family Neovenatoridae was created as a clade within Allosauroidea. This family encompassed Neovenator, Aerosteon, Australovenator, Chilantaisaurus, Fukuiraptor, Orkoraptor, and Megaraptor. The majority of these genera are now classified as megaraptorans, and in 2010, the megaraptorans were believed to be highly-derived allosaurs. The very same report also stated that Neovenator itself, the namesake specimen of Neovenatoridae, was unequivocally an allosauroid and also was either a carcharodontosaur or a close relative (Benson et al 2010, pages 71-72).

Then in 2012, an abstract was published which stated the following: “Megaraptor and its close relatives were poorly known carnivorous dinosaurs that inhabited South America, Australia, Asia, and possibly Africa, during Early to Late Cretaceous times. These theropods became relevant in the last years with the discovery of more complete skeletons. Recent phylogenetic analyses have viewed Megaraptor and its close relatives within a monophyletic group named as Neovenatoridae. This clade includes Megaraptor, Aerosteon, Orkoraptor, Chilantaisaurus, Fukuiraptor, Neovenator, and Australovenator. Neovenatorids were considered members of Allosauroidea, and particularly as the sister group of Carcharodontosauridae, as a clade of allosauroids that survived up to the end of the Cretaceous. However, we found anatomical information that supports that neovenatorids are a non-monophyletic group, and that Megaraptor and related genera are deeply nested within Coelurosauria and closely related to the Asiamerican Tyrannosauridae. Among coelurosaurian synapomorphies, these theropods share elongate metacarpals, ilium with enlarged fossa cuppedicus, distal end of tibia with a flat facet for the reception of the ascending process of the astragalus and gracile fibula and metatarsals. The Asian genus Fukuiraptor is recovered as the basalmost form of this new coelurosaurian clade. The phylogeny proposed here indicates that Neovenator is remotely related to Megaraptor and its kin, and indicates that this taxon is more closely related to Carcharodontosauridae, rather than with Coelurosauria. Chilantaisaurus from the Early Cretaceous of China is considered as an uncertain Coelurosauria. The newly recovered theropod clade considerably improves our knowledge about the scarcely documented basal radiation of coelurosaurs, filling a 15 MY gap in tyrannosauroid evolution” (Novas et al 2012, page R33)

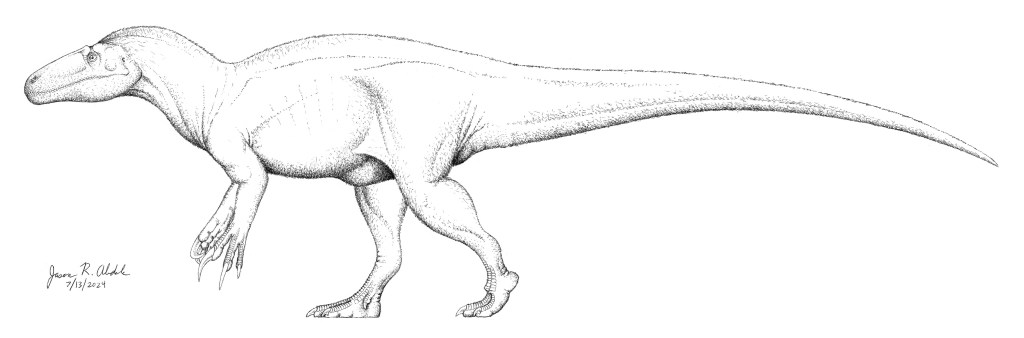

While the megaraptorans were thought of for some time to be nested within the clade Carcharodontosauria, they are now thought of by some paleontologists to actually be distant cousins of the tyrannosaurs, and therefore they likely had primitive feathers on their bodies. Recent studies have suggested that the megaraptorans are a group within the clade Coelurosauria, which is exactly what Fernando Novas stated back in 1998 when Megaraptor was named. In fact, Rolando et al (2022) stated that the megaraptorans are the sister group to the tyrannosauroids (Novas et al 2012, page R33; Novas et al 2013, page 174; Porfiri et al 2014, pages 35-55; Apesteguía et al 2016: e0157793; Rolando et al 2022: 6318).

In 2013, the family Megaraptoridae was created which included Megaraptor and its closest relatives. However, the 15 foot long Fukuiraptor of Japan is believed to be a basal form of the megaraptoran group, and is situated just outside of and basal to Megaraptoridae (Novas et al 2013, page 174). With the discovery of the megaraptorid Murusraptor, our knowledge of megaraptorid anatomy greatly improved. Two 2016 reports stated that the megaraptorans were tyrannosauroids, and Coria and his colleagues stated that they were an offshoot of the family Tyrannosauridae (Coria et al 2016: e0157973; Motta et al 2016, pages 239, 245-246). However, unlike the tyrannosaurs with their characteristically short arms, megaraptoran arms were gigantic. Their arms were long and well-muscled with an enormous hooked claw on the thumb, a smaller-but-still-big claw on the middle finger, and a small claw on the third finger. Clearly, the megaraptorans were placing a heavier emphasis on grabbing things with their hands rather than with their jaws (Rolando et al 2023, pages 1,804-1,823).

In terms of where the megaraptorans came from, since the 15 foot long Fukuiraptor is regarded as a basal member within Megaraptora, and since the majority of derived genera under Megaraptoridae are found almost exclusively within the Southern Hemisphere, it’s believed that the megaraptorans evolved within Asia sometime between 150-130 MYA during the late Jurassic or early Cretaceous, and then afterwards spread southwards during the middle Cretaceous (Bell et al 2016, page 473). Once they arrived in the south, they got bigger and bigger. Most megaraptorans were medium-sized carnivores measuring 20-25 feet long. The largest-known megaraptoran, the recently-named Maip macrothorax is estimated to have measured 30 feet long (Lamanna et al 2020, pages 255-294; Rolando et al 2022: 6318). If it’s true that the enigmatic giant North American theropod Siats is a megaratoran, as has been suggested by some authors, then this would nudge Maip aside as the largest member of that group (Naish and Cau 2022: e12727).

Megaraptor lived in a biologically diverse environment containing numerous herbivorous and carnivorous dinosaurs. However, Megaraptor might have been the top predator within its particular ecosystem in prehistoric Argentina 90 million years ago, since there’s no evidence of carnivorous dinosaurs of larger size within those rock layers except for some carcharodontosaurid teeth. Megaraptor shared its world with three species of titanosaur sauropods (Baalsaurus, Futalognkosaurus, and Malarguesaurus), three species of unenlagiid raptors (Neuquenraptor, Pamparaptor, and Unenlagia), the 3 foot long alvarezsaurid Patagonykus, the 13 foot long abelisaur theropod Elemgasem, the fish Leufuichthys, the turtles Portezueloemys and Prochelidella, and the pterosaur Argentinadraco. Unidentified remains ascribed to iguanodontian ornithopods, nodosaurid ankylosaurians, crocodiles, and birds have also been found here.

Megaraptor namunhuaiquii. © Jason R. Abdale (July 13, 2024).

If you enjoy these drawings and articles, please click the “like” button, and leave a comment to let me know what you think. Subscribe to this blog if you wish to be immediately informed whenever a new post is published. Kindly check out my pages on Redbubble and Fine Art America if you want to purchase merch of my artwork. Also, please consider becoming a patron on my Patreon page so that I can afford to purchase the art supplies and research materials that I need to keep posting art and articles onto this website. And, as always, keep your pencils sharp.

Bibliography

Apesteguía, Sebastián; Smith, Nathan D.; Juárez Valieri, Rubén; Makovicky, Peter J. (2016). “An Unusual New Theropod with a Didactyl Manus from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina”. PLOS ONE, volume 11, issue 7: e0157793 (July 13, 2016).

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0157793.

Bell, Phil R.; Cau, Andrea; Fanti, Federico; Smith, Elizabeth T. (2016). “A large-clawed theropod (Dinosauria: Tetanurae) from the Lower Cretaceous of Australia and the Gondwanan origin of megaraptorid theropods”. Gondwana Research, volume 36 (August 2016). Pages 473-487.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281548924_A_large-clawed_theropod_Dinosauria_Tetanurae_from_the_Lower_Cretaceous_of_Australia_and_the_Gondwanan_origin_of_megaraptorid_theropods.

Benson, Roger B. J.; Carrano, Matthew T; Brusatte, Stephen L. (2010). “A new clade of archaic large-bodied predatory dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) that survived to the latest Mesozoic”. Naturwissenschaften, volume 97, issue 1. Pages 71-78.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272152523_A_new_clade_of_archaic_large-bodied_predatory_dinosaurs_Theropoda_Allosauroidea_that_survived_to_the_latest_Mesozoic.

Calvo, Jorge O.; Porfiri, Juan D.; Veralli, Claudio; Novas, Fernando E.; Poblete, Federico (2004). “Phylogenetic status of Megaraptor namunhuaiquii Novas based on a new specimen from Neuquén, Patagonia, Argentina”. Ameghiniana, volume 41, issue 4 (December 30, 2004). Pages 565-575.

http://170.210.83.59/bitstream/handle/uncomaid/17798/Administrador%2C%2BApa1109%2C565-575%2BCalvo%2BPorfiri.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Coria, Rodolfo A.; Currie, Philip J. (2016). “A New Megaraptoran Dinosaur (Dinosauria, Theropoda, Megaraptoridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia”. PLOS ONE, volume 11, issue 7 (July 20, 2016): e0157973.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0157973.

Lamanna, Matthew; Casal, Gabriel Andrés; Martinez, Rubén Dario Francisco; Ibiricu, Lucio Manuel (2020). “Megaraptorid (Theropoda: Tetanurae) Partial Skeletons from the Upper Cretaceous Bajo Barreal Formation of Central Patagonia, Argentina: Implications for the Evolution of Large Body Size in Gondwanan Megaraptorans”. Annals of Carnegie Museum, volume 86, issue 3 (November 30, 2020). Pages 255-294.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346643017_Megaraptorid_Theropoda_Tetanurae_Partial_Skeletons_from_the_Upper_Cretaceous_Bajo_Barreal_Formation_of_Central_Patagonia_Argentina_Implications_for_the_Evolution_of_Large_Body_Size_in_Gondwanan_Megara.

Motta, Matias J.; Rolando, Alexis M. Aranciaga; Rozadilla, Sebastian; Angolin, Federico E.; Chimento, Nicolas R.; Egli, Federico Brisson; Novas, Fernando E. (2016). “New theropod fauna from the upper Cretaceous (Huincul Formation) of Northwestern Patagonia, Argentina”. In Khosla, A.; Lucas, S. G., eds., Cretaceous Period: Biotic Diversity and Biogeography. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 71 (2016). Pages 231-253.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304013683_NEW_THEROPOD_FAUNA_FROM_THE_UPPER_CRETACEOUS_HUINCUL_FORMATION_OF_NORTHWESTERN_PATAGONIA_ARGENTINA.

Naish, Darren; Cau, Andrea (2022). “The osteology and affinities of Eotyrannus lengi, a tyrannosauroid theropod from the Wealden Supergroup of southern England”. PeerJ, volume 10: e12727 (July 7, 2022).

https://peerj.com/articles/12727/.

Novas, Fernando E. (1998). “Megaraptor namunhuaiquii, gen. et sp. nov., a large-clawed, Late Cretaceous theropod from Patagonia”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, volume 18, issue 1 (March 1998). Pages 4-9.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254313700_Megaraptor_namunhuaiquii_gen_et_sp_nov_a_large-clawed_Late_Cretaceous_theropod_from_Patagonia.

Novas, Fernando E.; Agnolín, Federico L.; Ezcurra, Martín D.; Canale, Juan I.; Porfiri, Juan D. (2012). “Megaraptorans as members of an unexpected evolutionary radiation of tyrant-reptiles in Gondwana”. Ameghiniana, volume 49 (Suppl): R33.

https://www.ameghiniana.org.ar/index.php/ameghiniana/article/view/868/1618.

Novas, Fernando E.; Angolin, Federico L.; Ezcurra, Martín D.; Porfiri, Juan; Canale, Juan I. (2013). “Evolution of the carnivorous dinosaurs during the Cretaceous: The evidence from Patagonia”. Cretaceous Research, volume 45 (October 2013). Pages 174-215.

Porfiri, Juan D.; Novas, Fernando E.; Calvo, Jorge O.; Agnolín, Federico L.; Ezcurra, Martin D.; Cerda, Ignacio A. (2014). “Juvenile specimen of Megaraptor (Dinosauria, Theropoda) sheds light about tyrannosauroid radiation”. Cretaceous Research, volume 51 (2014). Pages 35-55.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263280059_Juvenile_specimen_of_Megaraptor_Dinosauria_Theropoda_sheds_light_about_tyrannosauroid_radiation.

Rolando, Alexis M. Aranciaga; Novas, Fernando E.; Calvo, Jorge O.; Porfiri, Juan D.; Dos Santos, Domenica D.; Matthew C. Lamanna (2023). “Reconstruction of the pectoral girdle and forelimb musculature of Megaraptora (Dinosauria: Theropoda)”. The Anatomical Record, volume 306, issue 7 (July 16, 2023). Pages 1,804-1,823.

https://anatomypubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ar.25128?af=R.

Rolando, Alexis M. A.; Motta, Matias J.; Agnolín, Federico L.; Manabe, Makoto; Tsuihiji, Takanobu; Novas, Fernando E. (2022). “A large Megaraptoridae (Theropoda: Coelurosauria) from Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of Patagonia, Argentina”. Scientific Reports, volume 12, issue 1 (April 26, 2022): Article number 6318.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360214319_A_large_Megaraptoridae_Theropoda_Coelurosauria_from_Upper_Cretaceous_Maastrichtian_of_Patagonia_Argentina.

Smith, Nathan D.; Makovicky, Peter J.; Agnolin, Federico L.; Ezcurra, Martin D.; Pais, Diego F.; Salisbury, Steven W. (2008). “A Megaraptor-like theropod (Dinosauria: Tetanurae) in Australia; support for faunal exchange across eastern and western Gondwana in the mid-Cretaceous”. Proceedings of the Royal Society B – Biological Sciences, volume 275, issue 1647 (September 22, 2008). Pages 2,085-2,093.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5311788_A_Megaraptor-like_theropod_Dinosauria_Tetanurae_in_Australia_Support_for_faunal_exchange_across_eastern_and_western_Gondwana_in_the_Mid-Cretaceous.

Smith, Nathan D.; Makovicky, Peter J.; Hammer, William R.; Currie, Philip J. (2007). “Osteology of Cryolophosaurus ellioti from the Early Jurassic of Antarctica and implications for early theropod evolution”. Zoological Journal of the Linnaean Society of London, volume 151, issue 2 (October 2007). Pages 377-421.

https://academic.oup.com/zoolinnean/article/151/2/377/2630870.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Awesome article!

Thank you.