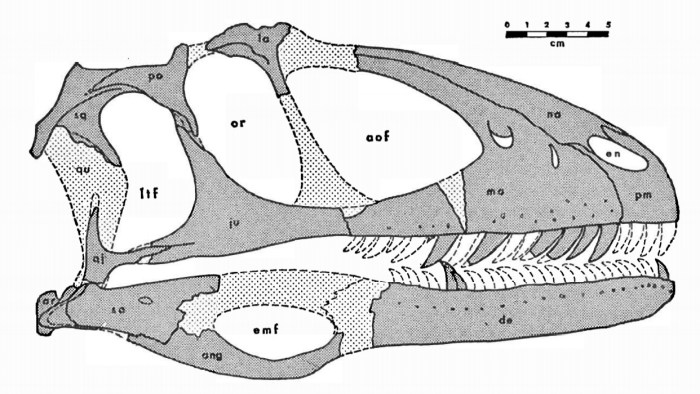

The skull of Deinonychus. This is the very first thing that appears on-screen in the first episode of the 1992 PBS documentary series The Dinosaurs! It’s a great series, by the way. You should watch it. Right now. Seriously. Get the heck off of this website, drop whatever else it is that you’re doing (Except holding your baby – don’t ever drop your baby. You’ll get arrested), find a copy of this show, and watch the whole thing, all four episodes, from start to finish. Why the hell are you still reading this? Aren’t you paying attention?! You’re making this dead Deinonychus seriously pissed off. Look at him giving you that side-eye! Well no wonder, because he has sideways-facing eyes, but he’s still giving you that look. Make no mistake, he’s judging you. He’s been dead for 110 million years, but he’s still judging you. Anyway…as long as you’re still here, you might as well read this article on why Deinonychus is so freakin’ awesome…

Introduction

If you live in or take a trip to New Haven, Connecticut and visit the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History (which is part of Yale University), you’ll eventually come to a room called the Great Hall; this is where the museum’s dinosaur skeletons are on display. Upon one of the walls which forms that large room is a gargantuan mural depicting what life looked like on Planet Earth millions of years ago. It is entitled “The Age of Reptiles”, painted by Rudolph Zallinger, and for a time it held the record of being the largest painting in the world. This impressive piece of artwork depicts life from the early Permian Period about 280 million years ago up until the end of the Cretaceous Period 66 million years ago. Although this painting is outdated now, it nevertheless depicted how dinosaurs were regarded for many decades – big, brutish, slow, and stupid (1).

Paleontology became a recognized scientific field in the early 1800s. Captivating discoveries of giant bones, giant teeth, and in some cases whole skeletons of long-lost antediluvian reptiles excited the imagination. Paleontology, and dinosaurs in particular, had been very popular from the middle of the 1800s into the 1920s. Discoveries of enormous skeletons in the American West, in northern and eastern Africa, and in the Gobi Desert kept public interest engaged and resulted in a great amount of research being done. However, during the early to middle part of the 20th Century, paleontology went into a slump. Dinosaurs had become passé. No surprise, in some respects, because there was a lot going on during that time that made people turn their attentions elsewhere. The Great Depression of the 1930s killed almost all work related to scientific research, and the field of paleontology very nearly went “extinct”. People were far more concerned with getting a job – any job – than with high-brow notions about prehistoric life. World War II resulted in academia stagnating in practically every field. 100% of everyone’s energy needed to be devoted to the war effort, and doing research on paleontology or digging up dinosaur bones was not only seen as useless, it was seen as frivolous and absurd. With the Atomic Age and the Space Race from the middle 1940s into the late 1960s, people were far more interested in rockets and astronomy than with fossils. Outer space was new and exciting, it was sexy and cool. Dinosaurs – those dull dim-witted lumbering behemoths which once roamed the earth and which were seemingly pre-destined for extinction – decidedly were not.

As such, for several decades, paleontology was reduced to being nothing more than a fringe science, something which only a handful of people worldwide had any interest in. Those few who indulged their imaginations by studying prehistoric life were mostly regarded by society as eccentric kooks. These were people who had seemingly wasted their lives devoting themselves to things which had absolutely no relevance to the modern world, with its whiggish obsession with progress and its tunnel-vision focus on futuristic discoveries and explorations. Digging up fossils and studying dinosaurs was not important. Beating the Soviets to the Moon was important. Developing new rockets was important. Building bigger and more destructive atomic bombs was important.

And then in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the dynamic abruptly changed. Dinosaurs once again captured not only the attention of professional academics but the attention of the general public. Dinosaurs had once again become popular, and we have one specific discovery to thank for that. In 1964, a remarkable find was made in south-central Montana which turned our understanding of dinosaurs, and paleontology as a whole, on its head. It was a small wolf-sized meat-eating dinosaur named Deinonychus. When its existence was made known to the world in 1969, it revolutionized the science of dinosaur paleontology and heralded the beginning of what became known as “the Dinosaur Renaissance”. From that moment on, our image of dinosaurs would never be the same.

Discovery

In 1931, Barnum Brown, a paleontologist working for the American Museum of Natural History, was looking for fossils on the Crow Indian Reservation in south-central Montana, about thirty miles southeast from the town of Billings, when he discovered the remains of a small dinosaur skeleton. The skeleton itself was in a very bad condition and it didn’t have a skull. Brown returned to Montana in 1932, and about a half-mile from where he found the skeleton, he found the fragmentary remains of a hand and foot, presumably from the same animal. These bones are currently in the collections of the American Museum of Natural History (collections ID code: AMNH 3015 and AMNH 3037) (2).

Barnum Brown surmised that this animal must be a theropod, a bipedal meat-eating dinosaur. He also recognized that these bones, although in a weathered condition, belonged to an animal which was quite unlike the dinosaurs which he had found before. This was no sluggish beast, but a nimble and lithe creature, presumably very active in its lifestyle. No doubt it would have been a terror to the other animals which it shared its realm with, a hungry jackal perpetually on the prowl for prey. In his notes, Barnum Brown gave this animal the name Daptosaurus agilis, “the agile devouring lizard”, in reference to its supposed athletic lifestyle and voracious appetite for flesh. However, Barnum Brown never actually published his findings, so the name was never officially recognized by the scientific community – it was just something that he had scribbled down on one of his papers. The fossils were stowed away in the vast collections of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, and there they lay, and in time Barnum Brown’s curious find was forgotten (3).

Over thirty years later in the summer of 1964, a paleontology dig team from Yale University’s Peabody Museum, led by Prof. John Ostrom, were prospecting for fossils within the Cloverly Formation in northern Wyoming and south-central Montana. Unlike the Morrison Formation of the late Jurassic Period and the Hell Creek Formation of the late Cretaceous Period, both of which have been intensely studied for decades and which are both world-famous for the large amounts of dinosaur bones which have been unearthed there, the Cloverly Formation of the middle Cretaceous Period is not well-known or well-studied. Very little research had been done on these rock layers, and very few fossils had been unearthed here. Professor John Ostrom’s 1964 survey hoped to shed a little bit more light on this otherwise obscure section of Mesozoic time. Unfortunately for Ostrom and his team, they hadn’t found very much. For weeks, they had trapsed up and down the badlands of south-central Montana, scouring these rocks for anything that they could find, but they had precious little to show for all of their effort. By the end of August, their time was almost up, and soon they would have to pack their bags and head back home to Connecticut (4).

About seven miles southeast of the town of Bridger, Montana, Prof. John Ostrom would make a remarkable discovery. On August 29, 1964 – the very last day of the dig season – Ostrom was being shown around by Grant Meyer, a senior member of the dig team, to all of the sites that he and his associates had taken note of as places where they ought to dig for fossils during the next time that they came out this way. A large cone-shaped hill known as “the Shrine” was the last stop on Meyer’s list of places to visit that day. At this hill, close to where the cars were parked, Ostrom spotted a claw sticking out of the ground (Note: Robert Bakker, who at the time was an undergrad student at Yale University and who served as a member of Ostrom’s dig team, claims that it was actually Grant Meyer who spotted the fossil first). Since all of the digging tools had been packed up for the day, Ostrom got down on his hands and knees and scraped away at the dirt using his fingernails. The two of them quickly realized that they had found the hand of a meat-eating dinosaur, with three long fingers, each one tipped with a massive eagle-like talon. Nearby was another large claw, which Ostrom initially thought belonged to the hand, but was later shown to have been fitted onto one of the toes of the foot; this claw was substantially larger than the claws on the other toes. Most curiously of all were sections of the tail, in which the vertebrae appeared to have been held in place by longitudinal rows of stiffened rod-like tendons. In life, this would have made the tail stiff and rigid (5).

Ostrom and his team spent as much time as they could digging up the specimens, but their time was running out and they couldn’t stay any longer. They realized that they would have to come back again to this spot next year and pick up where they left off. In fact, Ostrom and his associates came back twice, in the summers of 1965 and 1966. They realized that they had not just one but several skeletons, presumably from the same species. The digging itself was long painstaking work. All of the specimens were disarticulated, with the bones spread out over a considerable distance, and it took a large amount of effort to collect the individual bones and then figure out which bone belonged to which skeleton (6).

It took John Ostrom and the Peabody Museum’s fossil preparators nearly three years to prepare all of the fossils and do a comprehensive assessment of everything that had been found. It was during his research that Ostrom came across some curious references to fossils of a small meat-eating dinosaur which Barnum Brown had found in south-central Montana back in the early 1930s. These bones apparently bore a strong similarity to the fossils which he and his team had recently unearthed. They had been stashed away in the AMNH’s fossils collections, and it seems that nobody had bothered to look at them since. Ostrom decided that he needed to investigate. Dr. Edwin H. Colbert, a paleontologist from the AMNH who gained notoriety for his research on the Triassic meat-eating dinosaur Coelophysis, forwarded the bones and Barnum Brown’s field records to Dr. Ostrom in New Haven to examine. These bones had only been partially prepared, and there was no “treatment report” (a report made by paleontologists and fossil preparators concerning what work had been done on the bones since they were collected) accompanying them. However, when he examined the bones, Ostrom recognized a strong similarity between the fossils which Brown had found back in the early 1930s and the fossils which he and his team had found recently. They undoubtedly came from the same animal (7).

Ostrom wrote up his findings in December 1968, and in February 1969 they were finally published. As stated earlier, Barnum Brown had proposed the name Daptosaurus agilis for the animal which he had found, but he never published it, so the name was never officially recognized by the scientific community. Rather than officially name the animal Daptosaurus, which Barnum Brown had provisionally named his creature, Ostrom decided to give the animal a different name – to the victor go the spoils. He officially named the animal Deinonychus, meaning “terrible claw”. The species name antirrhopus meant “counter-balance”, in reference to its long stiffened tail which it presumably used as a balancing pole to keep its balance while making sharp turns and leaping into the air (8).

Description

In February 1969, John Ostrom published a 17-page report in the journal Postilla which outlined the discovery of Deinonychus, officially registered its name, and gave a summary of its anatomy and cladistic classification. However, more information was needed. A few months later in July 1969, Ostrom published a comprehensive assessment of Deinonychus’ skeleton, describing everything in extremely specific detail; the entire report measured 172 pages long. You can access both reports from the bibliography of this web article.

John Ostrom identified Deinonychus as a member of the theropod family Dromaeosauridae. It just so happened that Dr. Edwin Colbert of the American Museum of Natural History and Dr. Dale Russell of the National Museum of Canada were doing research on Dromaeosaurus (a small theropod dinosaur which had been found in Alberta, Canada during the early 1920s) at the same time that Ostrom was analyzing the fossils of Deinonychus which he had found in Montana. Conversations between Ostrom, Colbert, and Russell about their research projects made them realize that Dromaeosaurus and Deinonychus were very similar and thus surely belonged to the same family of meat-eating dinosaurs. These conversations also made them realize that the dromaeosaurids were quite unlike other theropods – small, agile, fast, with a large hook-shaped claw on each foot (9).

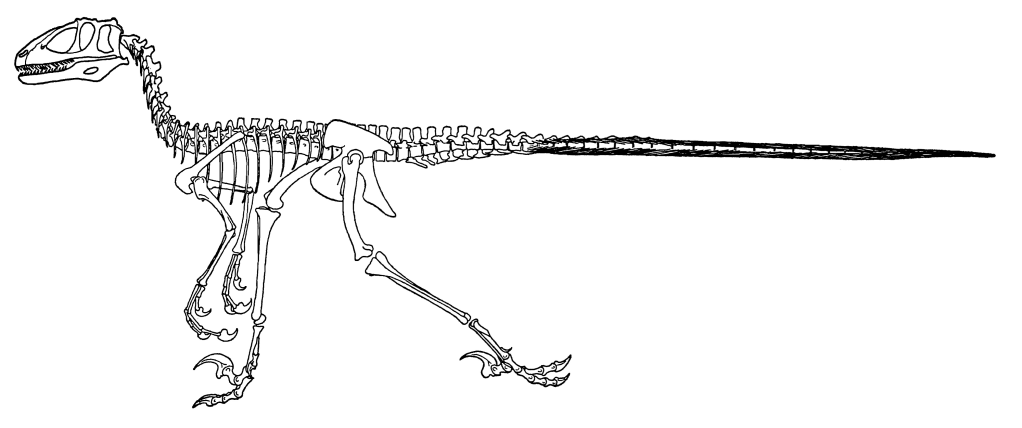

The skeleton of Deinonychus, illustrated by Robert Bakker. Note the short length of the hip bones in this drawing, which was a mistake – the pubis and the ischium were much longer, and the pubis was angled backwards, as seen in birds. Image from John H. Ostrom (1969), “Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an Unusual Theropod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana”. Peabody Museum Bulletin, bulletin 30 (July 1969). Page 142. Image courtesy of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. Image used with permission.

The skull of Deinonychus, right side view and the underside of the top jaw. Images from John H. Ostrom (1969), “Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an Unusual Theropod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana”. Peabody Museum Bulletin, bulletin 30 (July 1969). Page 15. Image courtesy of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. Image used with permission.

Deinonychus measured about 3 feet tall and 10 feet long. It was by no means the largest meat-eating dinosaur that had been found, or the smallest for that matter, but at the time of its discovery, it was the most intriguing. The thing which identified Deinonychus and other “raptor” dinosaurs are the large “killing claws” on the feet. These enlarged hook-shaped toe claws, which were twice as large or larger than the other claws on the feet, were clearly used for a distinctive method of attacking and killing its prey. This implied that this animal lived a very active lifestyle. Indeed, the entire animal’s anatomy seemed to radiate an air of athleticism, possessing a light greyhound-like frame with slight delicate bird-like bones, large grasping hands, and most curious of all, a long tail which had been stiffened into a pole by the addition of row-upon-row of ossified tendons running all along its length, except for where the tail attached to the hip, allowing the tail to pivot at the tail’s base. In Ostrom’s mind, this tail served much the same function as a balancing pole used by a tightrope-walker so that the animal could maintain its balance when leaping onto its prey or making sharp tight turns when running at high speed.

The skeleton of Deinonychus, on display at the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois. Photograph by Jonathan Chen (August 11, 2018). Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Deinonychus_FMNH.jpg.

In 1974, another Deinonychus skeleton was discovered in Montana, this time by a dig team from Harvard University, and it was housed within the university’s Museum of Comparative Zoology (collections ID code: MCZ 4371). This particular skeleton contained bones which Ostrom’s skeletons didn’t have, including sections of the hip, and Ostrom was forced to revise his depiction of this animal. His assessment was published two years later in 1976 (10).

Deinonychus and the Dinosaur Renaissance

John Ostrom himself referred to the discovery of Deinonychus as one of the most important discoveries in paleontology, because it was such a game-changer for everything that we assumed we knew about dinosaurs (11). In John Ostrom’s words, “Deinonychus certainly opened up a whole new window in viewing these animals. This animal clearly indicated extreme agility, activity, perhaps even intelligence, but these were very very sophisticated animals unlike our previous image of what dinosaurs were about” (12).

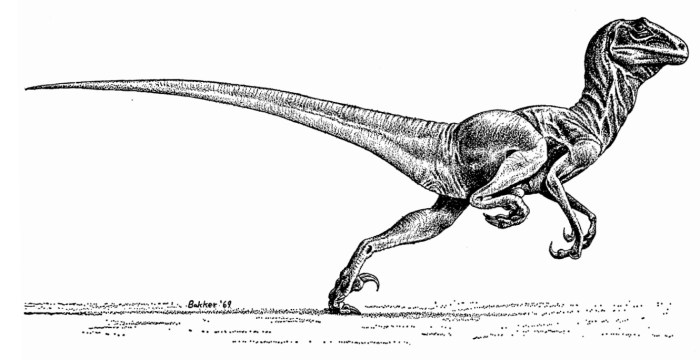

A reconstruction of Deinonychus, illustrated by Robert Bakker. Image from John H. Ostrom (1969), “Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an Unusual Theropod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana”. Peabody Museum Bulletin, bulletin 30 (July 1969). Image courtesy of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. Image used with permission.

The discovery of Deinonychus kick-started a sea-change in paleontology. Beginning in the early 1970s, paleontologists were forced to re-think pretty much everything that they thought they knew about dinosaurs. Images and perceptions of dinosaurs as slow stupid plodders, which had been regarded as scientific dogma ever since the 1820s, were thrown out the window. This fervent period of iconoclastic scientific re-examination would become known as “the Dinosaur Renaissance”.

Following his work on Deinonychus, John Ostrom turned his attention towards pterosaurs. In 1970, he visited the Teylers Museum in Haarlem, Netherlands to examine what was said to be a fossil pterosaur that the museum had in its collections. However, when Ostrom saw it, he immediately knew that it had been misidentified – it was actually a specimen of Archaeopteryx, the oldest-known bird. Archaeopteryx fossils are extremely rare. At the time, only three were known to exist, and this one was the fourth. To Ostrom’s eye, the anatomical similarities between Deinonychus and Archaeopteryx were startling. This led him to wonder, if birds and meat-eating dinosaurs are so similar to each other, then could it be possible that they were related? To be fair, it was not a new idea. Back in the 19th Century, the famous British naturalist Thomas Huxley had proposed that dinosaurs and birds shared a common ancestor. However, Ostrom decided to take this one step further, and he proposed something radical: birds were directly descended from dinosaurs. Ostrom first pitched his theory in 1973, where it was almost universally rejected. In 1976, Ostrom published a paper entitled “Archaeopteryx and the Origin of Birds”, and in this essay, he laid out over 200 anatomical similarities that birds shared with theropod dinosaurs. In 1986, one of Ostrom’s colleagues at Yale University named Dr. Jacques Gauthier used cladistic analysis to prove that birds were the evolutionary descendants of dinosaurs (13).

Increasingly, dinosaurs came to be seen as energetic active animals, more akin in their physiology to many warm-blooded mammals alive today than to sluggish cold-blooded reptiles. This led to an interesting question – could it be possible that dinosaurs were also warm-blooded? This couldn’t be, because dinosaurs were reptiles, and all reptiles alive today are cold-blooded. However, scientists observed that birds almost certainly evolved directly from dinosaurs, and all birds alive today are warm-blooded. So, could it have been possible that dinosaurs, like their bird descendants, were warm-blooded too? The debate whether dinosaurs were cold-blooded or warm-blooded would prove to be one of the most contentious in paleontology for decades afterwards, and it still has not been conclusively resolved (14).

What about dinosaur behavior? Were dinosaurs social? Did they communicate with each other? Did they care for their young? Since the 1920s, we’ve known that dinosaurs laid eggs, but did dinosaurs care for their young like birds? In the summer of 1978, Jack Horner and Bob Makela were prospecting for fossils in Montana, and one of their regular stops was a rock and fossil shop owned by Marion Brandvold located in Bynum, Montana. Earlier, she had found some small bones while taking a walk, and showed them to Horner and Makela so that they could identify them. They immediately recognized what they were – the bones of baby dinosaurs, something which had never been found before. The bones did not appear to be well-formed: they were delicate and fragile, and the babies would likely not have had the physical strength to move about much and forage for food on their own. Therefore, the parents must have brought food to them. The dinosaur was named Maiasaura, “the good mother lizard”, due to the theory that this particular dinosaur took very good care of its young. Surveys of the area revealed several nests located close to each other, about 25 to 30 feet apart from each other, which was also the length of the adults, so the nests must have been densely-packed in populated colonies, just like some birds. The discovery of the Maiasaura nesting colony, and the discovery of baby dinosaurs, proved two things: first, that some dinosaurs did indeed live in social groups, and second, that some dinosaurs did indeed care for their young (15).

Throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s, dinosaurs were increasingly regarded as biologically distinctive, physically active, and behaviorally complex. One of those who championed John Ostrom’s ideas the loudest was one of his former students, a man who would become one of the most famous paleontologists of the 20th Century – Robert Bakker. He firmly believed that dinosaurs were warm-blooded active animals, perhaps brightly colored, and possessing complex social behaviors. In 1986, Bakker published his ideas in a book entitled The Dinosaur Heresies, and it would prove to be a seminal book in the history of dinosaur paleontology. In his view, contrary to the image which had been established by the Victorians and perpetuated ever since, dinosaurs were not giant lizards – they were birds masquerading as lizards.

But if it was true that birds were directly descended from dinosaurs, then where was the hard proof? Archaeopteryx was indeed a primitive bird, but it was still, nevertheless, a bird. Were there any “missing link” species – dinosaurs which possessed rudimentary feathers, but were not yet capable of flight? During the 1980s and 1990s, it had been speculated that some meat-eating dinosaurs might have been covered in feathers (the artist Gregory Paul was an early supporter of this idea), but there was no actual hard evidence to prove it. That changed in 1999. In Liaoning Province, China in rocks dated to the Yixian Formation of the early Cretaceous Period (approximately 130-122 million years ago), a small skeleton measuring only 3 feet long was discovered. The skeleton was badly crushed and somewhat disarticulated, but what was remarkable about it was that it clearly preserved evidence of primitive feathers being present on its neck, body, and arms. The creature was named Sinornithosaurus, “the Chinese bird-lizard”, and its discovery was an immediate sensation. Here was physical proof that at least one dinosaur had feathers on its body. The fact that it was a raptor was even more noteworthy. Not long afterwards, other fossil dinosaurs were found in China fitted with feathery fuzz (16).

A restoration of Sinornithosaurus. Model by Brian Douglas Cooley. Photograph by Onofrio Louis Mazzatenta. National Geographic magazine (October 1999).

Sinornithosaurus was one of the oldest raptor dinosaurs which are known to exist. Since this animal possessed feathers, this implies that other raptor dinosaurs which evolved later also had feathers, as well as any raptors which existed earlier such as Utahraptor. Indeed, with the discovery of Microraptor, a highly-evolved raptor which possessed full-fledged feathered wings, this idea was confirmed. Nowadays it is acknowledged that all raptors, including Deinonychus, sported a coat of feathers. This was quite a turn-around from the classic scaly reptilian image which we always associated with dinosaurs since the 1820s. In fact, the paleo-artist Stephen Czerkas (1951-2015) retroactively refitted his Deinonychus sculptures, originally made in 1989, with feathers in 2000 once it was established that raptors had feathers instead of scales.

Deinonychus sculptures, made by Stephen Czerkas, on display in the Dinosaur Museum in Blanding, Utah. Note that two of these sculptures have been refitted with feathers. Photograph by Mramoeba (April 15, 2019). Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Dinosaur_Museum,_Blanding,_Utah_04.jpg.

Deinonychus. © Jason R. Abdale (November 8, 2023).

Deinonychus and Popular Culture

From 1969 until 1993, Deinonychus was one of the most famous dinosaurs in the world, achieving celebrity status as one of the most vicious meat-eating dinosaurs ever. It was only with the release of the movie Jurassic Park in 1993 that a hitherto little-known carnivore named Velociraptor seized the spotlight and pushed Deinonychus forcefully into the rear.

Velociraptor had been discovered in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia during the 1920s. However not much was known about it since only partial remains had been found. What was certain was that the real-life Velociraptor was nowhere near as big as the creatures portrayed in the movie, measuring just 2 feet tall and 6 feet long, and scarcely weighing 30 pounds. Ever since its discovery, Velociraptor had been a somewhat obscure meat-eating dinosaur which not many people knew about, but all that changed with Jurassic Park.

In fact Michael Crichton, the author of the Jurassic Park novel which was published in 1990, based his raptors on the wolf-sized Deinonychus of Montana, not the small turkey-sized Velociraptor of Mongolia. Crichton followed a school-of-thought which had gained traction during the 1980s which stated that Deinonychus was a larger North American species of Velociraptor. If you look at Gregory Paul’s artwork during that time, you’ll see that he often illustrates his Deinonychus with an elongated concave Velociraptor-like skull rather than the high triangular skull that is typically shown in Deinonychus restorations. In both the 1990 book Jurassic Park and the 1993 movie adaptation, the paleontologist Dr. Alan Grant and his dig team were excavating Velociraptor bones in the badlands of Montana instead of in the Gobi Desert – they were actually digging up Deinonychus bones, and the raptors hunting Lex and Tim in the kitchen were supposed to be Deinonychus as well. Another reason why Michael Crichton made the change from Deinonychus to Velociraptor in his book was because he thought that Velociraptor was a cooler-sounding name (17).

Since the movie Jurassic Park debuted in 1993, Velociraptor has been regarded as the quintessential “raptor”. Its name became a household word, and Deinonychus was regrettably cast aside. One might wonder how people would react if they were informed that their appreciation for Velociraptor was based upon a mass case of mistaken identity. A raptor, by any other name, would kill just as sweetly.

Conclusion

In the past, dinosaurs were largely regarded as giant cold-blooded lizards, lumbering around in hot humid fetid swamps, predestined to be replaced by a higher class of animal which was more fit to inherit the earth. That changed in 1964 with the discovery of Deinonychus in the Montana Badlands. When its existence was publicly made-known in 1969, it shook the world of paleontology. The old “classical” image of dinosaurs began to change from stupid tail-dragging brutes to complex animals with remarkable physiological characteristics, intricate social lives, and even possessing a degree of intelligence. Furious academic debates erupted concerning just how dynamic dinosaurs really were, and just how closely related they were to our flying feathered friends. The general public soon caught wind of all of these new developments, and their interest was piqued. After being dismissed by people for decades, dinosaurs once again began to increase in popularity. With the release of Jurassic Park in movie theaters in 1993, the whole world caught “dinosaur fever”, and they arguably became more popular than they had ever been before. We have just one creature to thank for all of that – Deinonychus, the dinosaur that changed the world.

Source Citations

- Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. “The Age of Reptiles Mural”; The Dinosaurs!, episode 2 – “Flesh on the Bones”. PBS, 1992.

- John H. Ostrom (1969), “A New Theropod Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana” (February 25, 1969). Postilla, volume 128. Page 4; John H. Ostrom (1969), “Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an Unusual Theropod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana”. Peabody Museum Bulletin, bulletin 30 (July 1969). Pages 7-8.

- Mark A. Norell, Eugene S. Gaffney, and Lowell Dingus, Discovering Dinosaurs in the American Museum of Natural History. New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1995. Pages 129-130; John H. Ostrom (1969), “Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an Unusual Theropod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana”. Peabody Museum Bulletin, bulletin 30 (July 1969). Page 5.

- John H. Ostrom (1969), “Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an Unusual Theropod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana”. Peabody Museum Bulletin, bulletin 30 (July 1969). Page 5; The Dinosaurs!, episode 2 – “Flesh on the Bones”. PBS, 1992.

- John H. Ostrom (1969), “A New Theropod Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana” (February 25, 1969). Postilla, volume 128. Page 2; John H. Ostrom (1969), “Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an Unusual Theropod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana”. Peabody Museum Bulletin, bulletin 30 (July 1969). Page 8; Natural History Magazine. “Day of the Deinos: Did predatory dinosaurs leave clues to their pack-hunting habits at kill sites?” by Desmond Maxwell (December 1999-January 2000); Beyond Bones – Blog of the Houston Museum of Natural Science. “Raptors – Group Hunters or Cannibals?”, by Robert Bakker (March 11, 2010); Yale News. “Yale’s legacy in ‘Jurassic World’”, by Mike Cummings (June 18, 2015); The Dinosaurs!, episode 2 – “Flesh on the Bones”. PBS, 1992; Paleoworld – “Killer Raptors”.

- John H. Ostrom (1969), “Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an Unusual Theropod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana”. Peabody Museum Bulletin, bulletin 30 (July 1969). Pages 8-9.

- John H. Ostrom (1969), “Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an Unusual Theropod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana”. Peabody Museum Bulletin, bulletin 30 (July 1969). Pages 8-9.

- John H. Ostrom (1969), “A New Theropod Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana” (February 25, 1969). Postilla, volume 128. Pages 1-17.

- John H. Ostrom (1969), “A New Theropod Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana” (February 25, 1969). Postilla, volume 128. Pages 1-3, 8; John H. Ostrom (1969), “Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an Unusual Theropod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana”. Peabody Museum Bulletin, bulletin 30 (July 1969). Page 11.

- John H. Ostrom (1976), “On a new specimen of the Lower Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Deinonychus antirrhopus”. Breviora, volume 439 (July 30, 1976). Pages 1-21.

- The Dinosaurs!, episode 2 – “Flesh on the Bones”. PBS, 1992.

- Dinosaur!, episode 3 – “The Tale of an Egg”. A&E, 1991.

- The Dinosaurs!, episode 1 – “The Monsters Emerge”. PBS, 1992; The Blog of Death. “John Ostrom”, by Jade Walker (August 22, 2005); Brendan Hanrahan, Great Day Trips in the Connecticut Valley of the Dinosaurs. Wilton: Perry Heights Press, 2004. Page 74.

- The Dinosaurs!, episode 2 – “Flesh on the Bones”. PBS, 1992.

- Dinosaur!, episode 3 – “The Tale of an Egg”. A&E, 1991; The Dinosaurs!, episode 3 – “The Nature of the Beast”. PBS, 1992.

- Xing Xu, Xiao-Ling Wang, and Xiao-Chun Wu, “A dromaeosaurid dinosaur with a filamentous integument from the Yixian Formation of China”. Nature, volume 401, issue 6750 (September 16, 1999). Pages 262-266.

- Yale News. “Yale’s legacy in ‘Jurassic World’”, by Mike Cummings (June 18, 2015).

Bibliography

Books:

- Hanrahan, Brendan. Great Day Trips in the Connecticut Valley of the Dinosaurs. Wilton: Perry Heights Press, 2004.

- Norell, Mark A.; Gaffney, Eugene S.; Dingus. Lowell. Discovering Dinosaurs in the American Museum of Natural History. New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1995.

Articles:

- Ostrom, John H. (1969). “A New Theropod Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana” (February 25, 1969). Postilla, volume 128. Pages 1-17. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4765/ad35c9a7cc474e6ca1061ea2eaecbebe054d.pdf.

- Ostrom, John H. (1969). “Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an Unusual Theropod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana”. Peabody Museum Bulletin, bulletin 30 (July 1969). Pages 1-172. http://peabody.yale.edu/sites/default/files/documents/scientific-publications/ypmB30_1969.pdf.

- Ostrom, John H. (1976). “On a new specimen of the Lower Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Deinonychus antirrhopus”. Breviora, volume 439 (July 30, 1976). Pages 1-21. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/3189704#page/51/mode/1up.

- Xu, Xing; Wang, Xiao-Ling; Wu, Xiao-Chun. “A dromaeosaurid dinosaur with a filamentous integument from the Yixian Formation of China”. Nature, volume 401, issue 6750 (September 16, 1999). Pages 262-266. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242880568_A_dromaeosaurid_dinosaur_with_a_filamentous_integument_from_the_Yixian_Formation_of_China

Websites:

- Beyond Bones – Blog of the Houston Museum of Natural Science. “Raptors – Group Hunters or Cannibals?”, by Robert Bakker (March 11, 2010). https://blog.hmns.org/2010/03/raptors-group-hunters-or-cannibals/.

- Fossil Crates. “Pack Hunting Raptors – What is the evidence?”, by Dr. Brian Curtice (May 21, 2020). https://www.fossilcrates.com/blogs/news/pack-hunting-raptors-what-is-the-evidence.

- Natural History Magazine. “Day of the Deinos: Did predatory dinosaurs leave clues to their pack-hunting habits at kill sites?” by Desmond Maxwell (December 1999-January 2000). https://www.naturalhistorymag.com/htmlsite/master.html?https://www.naturalhistorymag.com/htmlsite/1299/1299_feature.html.

- The Blog of Death. “John Ostrom”, by Jade Walker (August 22, 2005). http://www.blogofdeath.com/2005/08/22/john-h-ostrom/.

- Yale News. “Yale’s legacy in ‘Jurassic World’”, by Mike Cummings (June 18, 2015). https://news.yale.edu/2015/06/18/yale-s-legacy-jurassic-world.

- Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. “The Age of Reptiles Mural”. https://peabody.yale.edu/exhibits/age-reptiles-mural.

Videos (listed according to date of broadcast):

- Dinosaur! Episode 3 – “The Tale of an Egg”. A&E, 1991.

- The Dinosaurs! Episode 1 – “The Monsters Emerge”. PBS, 1992.

- The Dinosaurs! Episode 2 – “Flesh on the Bones”. PBS, 1992.

- The Dinosaurs! Episode 3 – “The Nature of the Beast”. PBS, 1992.

- Paleoworld. Season 4, episode 7 – “Killer Raptors”. The Learning Channel, 1997.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment